Session 6

Building a Scanner

Quote of the Day

Kent Beck tells the story of Prune (Facebook login required). Prune is a code editor, so it needed a scanner. My favorite quote is:

We wrote an ugly, fragile state machine for our typeahead, which quickly became a source of pain and shame.

You will soon likely experience these emotions, perhaps even about a state machine. They are normal for compiler writers. They are normal for programmers.

Context: DFAs and Lexical Analyzers

For the last three sessions [ 3 | 4 | 5 ], we have been learning the tools we need to build a scanner for a compiler. We use regular expressions to specify the concrete syntax of tokens in a programming language. We then convert these regular expressions into a deterministic finite state automaton, a particular kind of state machine. Finally, we implement a scanner as a program that implements the state machine. The scanner performs lexical analysis: it recognizes the tokens in a source program.

Today, we put all of these tools together to implement a scanner for a simple language that describes ASCII graphics. We will also use this simple example as a way to consider some of the practical issues we face when writing a program to do lexical analysis.

Today's Task: Building a Scanner

Consider a simple language for drawing simple ASCII diagrams that I call "AGL", for ASCII Graphics Language. I did not create this language from scratch; it is a variant of a language I've seen several times over the years, most recently as an example for another programmer's parser generator. It has just enough complexity to be a good testbed for us to apply the ideas we have been learning.

Each statement in AGL describes one or more lines of output. For example:

4 12 X;

says that we want four lines of text, each consisting of twelve

Xs:

XXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXX

A statement can also describe something with more structure. For example:

8 4 b 4 X 4 b;

describes a block of eight lines, in which each line consists

of four blanks, four Xs, and four more blanks.

Using these two AGL statements in this fashion:

4 12 X; 8 4 b 4 X 4 b; 4 12 X;

creates a program that describes the following picture, a big "I":

XXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXX

XXXX

XXXX

XXXX

XXXX

XXXX

XXXX

XXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXX

We can describe the grammar for AGL in BNF notation:

drawing ::= row*

row ::= count chunk+ ";"

count ::= INTEGER

chunk ::= INTEGER CHAR

The terminals ";",

INTEGER, and CHAR are terminals:

- ";" is a self-delimiting character that terminates row statements.

INTEGERis a non-negative integer.CHARis a single character.

Some characters are interpreted literally, while others are interpreted as codes. For example, the "X" in the program above corresponds to an "X" in the image, while the "b" indicates a blank.

Let's build a scanner for AGL. Our scanner doesn't need to worry about the distinction between types of characters. It can simply return terminator, integer, and string tokens.

In Session 2, we saw a scanner for the language Fizzbuzz, a simple language that can be used to solve the mythical interview question of the same name. I wrote that scanner in an ad hoc fashion, attacking the Fizzbuzz language spec with only my meager skills as a Python programmer. The language is simple enough that I was able to write a correct and complete scanner in a short time, though with some trial and error.

After Sessions 3, 4, and 5, though, we know a technique for designing scanners using regular expressions and finite state machines. This technique enables us to more confidently write a complete and sound scanner, even for a more complex language, in a reasonable amount of time.

Let's practice using the techniques you've learned to design and implement a scanner for AGL before you dive the rest of the way into writing a scanner for the more complex source language of your project.

Exercise: Design

Design a scanner for AGL using regular expressions and finite state machines.

Follow the steps we've learned:

- Write regular expressions for the tokens.

- Convert each regular expression into a (possibly non-deterministic) finite state automaton.

- Convert the NFAs into a DFA.

At the end, you should have a single DFA that accepts the tokens in AGL.

A Design

Here are regular expressions for AGL tokens:

terminator → ; number → 0 | [1-9][0-9]* string → [a-zA-Z]

The descriptions of AGL that I've seen don't limit what the graphics characters can be, so any character that doesn't match as a terminator or number should count. They also seem to allow strings of more than one character. But let's keep things simple and use single alphabetic characters.

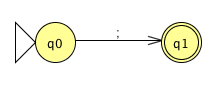

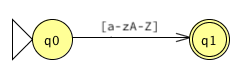

We use these regular expressions to generate deterministic finite state machines for each of the token types. The first two are for the terminator and the string:

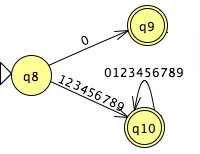

Finally, the machine for integer tokens is familiar by now:

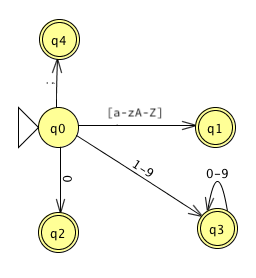

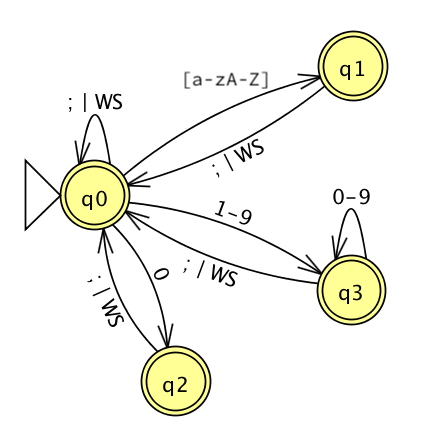

Using the techniques that we learned last session, or a tool such as JFLAP, we combine the multiple DFAs into a single NFA, and then convert the non-deterministic finite machine into a deterministic machine. There is no ambiguity in AGL's tokens, so this is straightforward:

We have omitted an important detail from our discussion of the state machines up to this point. After the scanner recognizes a token, it has to return to the start state so that it can look for the next token. Usually, we make this part of the machinery of the scanner we write to implement the DFA.

For a language this simple, we have another option: Add transitions from the accepting states back to the start state, labeled with any character that can terminate a token.

A terminator or whitespace can indicate the end of any token, so we can add arcs back from states 1-3. State 4 is an interesting case, because don't need any arc back; the terminator is self-delimiting. What happens if we add an ε arc back to State 0 and then convert the now-NFA to a DFA? It disappears! We don't really need the state at all.

Finally, when we are looking for a token, we can always consume whitespace and remain in the same state. This gives us a final DFA that looks like this:

Look how well the techniques worked... We end up with a clean, straightforward machine of four states, all of which accept tokens. (State 0 accepts the statement terminator.)

I used JFLAP to create my NFAs, combine them into one NFA, convert it to a DFA, and minimize the DFA. You might consider using JFLAP or a similar tool on your project. It takes a while to learn a new tool, but the payoff can be worth it.

For your convenience, the Session 6 code directory contains

a JFLAP source file for my final DFA,

dfa.jff.

I used it to create my images, so it isn't suitable for use to

convert NFAs to minimal DFAs. +

Use it to experiment, if you'd like.

JFLAP requires single characters for transition labels.

Toward an Implementation

We can use your DFA (or mine) to write a scanner for AGL. Let's use Python.

The scanner will need a couple of pieces of infrastructure:

- a way to represent states

class State(Enum):

looking = 1

zero = 2

integer = 3

string = 4

Token class

we can use today.

def scan(program):

tokens = [] # list of tokens to return

accum = '' # for building multi-character tokens

# the state machine

state = State.looking

pos = 0

while pos < len(program):

...

return tokens

Reminder: Your Klein scanner does not read all of the tokens up front. It returns one token at a time, upon request from the parser or other client.

An Implementation

Here is the code for a simple scanner. The code directory also includes the AGL program example we saw earlier as a source file.

The scan function is more than a page long, but

there is a pattern:

switch on state

switch on input

create a token?

change the state?

advance position

The accumulator variable accum keeps track of the

characters the scanner has seen that need to become part of a

token later. The function sets the accumulator back to empty

as soon as it uses them to create a token.

Note that this scanner follows the state machine in every detail. For your project, I suggest that you follow as closely as possible the state machine you create for Klein's concrete syntax. As a language becomes more complex, you will find more and more value in following the state machine. This value includes increased confidence in the completeness and soundness of the code and in a corresponding decrease in debugging time. If you need to optimize this code later for performance reasons, you always can.

Lexical analyzer generators such as Lex, Flex, JLex, and JavaCC generate code that follows a state machine exactly, state-by-state. That's one of the reasons that the scanners they generate are so efficient, and easy to show they are correct.

Lexical Errors

The AGL scanner does not throws Python errors!

The client code catches any errors thrown by the scanner and prints them gracefully. We do not want the user of the scanner to see that the scanner is implemented in Python. This is an essential condition of your project. To conform to the project spec, your compiler (or whatever client code uses the scanner) must catch the errors that the scanner generates. For example:

try:

tokens = scan(program_text)

except Exception as e:

error_message = str(e)

...

My compiler can display the error message in its own way and then terminate gracefully.

Pragmatic Issues in Writing Scanners

Regular expressions and finite state automata are great tools for helping us to design lexical analyzers, but when we turn to actually writing a program we still face a lot of choices. The issues that make up the concrete choices we make when writing code are sometimes called pragmatics. These practical issues are very important to us programmers when it comes time to actually write code!

Last session we discussed one pragmatic issue: how to implement a DFA in code. I supplemented that discussion with sample programs that demonstrate implementing states as integers, as functions, as objects, and as entries in a state table that drive generic processing loop.

The "Shape" of the Scanner

Those programs are simple enough that it's hard to see the basic "shape" of a scanner. Our AGL scanner uses a simple algorithm that you'll see in many state-machine programs:

- maybe create a token

- update the state (if necessary)

- advance to the next character

To implement a function that returns a single token, we might expand this outline with a bit more detail into:

skip whitespace

state = START

content = ''

while state is live and not final:

peek at next char

break with error if none

change state based on (state,char)

usually consume char

usually content += char

if dead:

break with error

# must be in a final state

return token based on the state and content

Notice that both this outline and the AGL scanner take care of another important practical manner: saving the characters our scanner sees so that it can create the semantic content of tokens. We need to know more than that our scanner has recognized an integer or a string: we need to which integer or string!

There are a few more pragmatic issues that you will want to consider as you implement your scanner.

Managing the Input Stream

A scanner often reads all of the characters from its input stream (often a file) into an array or a vector of strings before processing. This makes it easy for the scanner to move back and forth in the input stream and to provide detailed feedback when the compiler encounters an error. This includes lexical errors found by the scanner as well as errors detected later in the process. In order to support error reporting downstream, each token can keep track of where there were found in the source file.

Working with Multiple DFAs

Writing a regular expression for each type of token results in several DFAs, one for each token type. This leaves us with a choice:

- If the choice of which DFA applies is deterministic, use the current character in the stream to select the DFA to run.

- Combine the individual DFAs into a single NFA with ε transitions, and then convert this to a single DFA.

- Consider each DFA in sequence. If one fails, backtrack in the stream and try the next one. If one matches, remember it. This is not recommended, due to the backtracking.

We can also use a hybrid approach that treats some token types differently (say, keywords and symbols) and processes the DFAs for the variable tokens (numbers and identifiers) individually.

Handling Keywords

Languages with even a few keywords usually require many, many states in a DFA in order to distinguish between keywords and identifiers, as there are many "special cases" in long character sequences.

One technique for managing this problem is to build a table of keywords and their tokens before scanning. Then, when the scanner reaches a terminal state for an identifier, check the table for a keyword match. If the string is found in the table, return a keyword token, else return an identifier token.

Matching the Longest Token

There may be other cases in multiple tokens can match the

same string, such as operators like + and

++. Unless the language specification says

otherwise, a scanner will usually match the longest sequence

of characters possible before accepting a token. Some

symbols, such as parentheses, are usually

self-delimiting, that is, they do not need to be

surrounded by whitespace in order to be recognized.

For tokens that are not self-delimiting, how can the scanner recognize the longest sequence possible?

- When the scanner hits a terminal state, record the token matched and the position in the input stream.

- When the scanner finally hits a dead state, it can return the longest token matched and set the stream to the character immediately following it, for processing next.

In most practical cases, a single character peek can enable the scanner to match such tokens with any backtracking.

Fixing Errors in Lexical Analysis

It is difficult for a compiler to detect meaningful errors at only the lexical analysis level. Consider the case of a misspelled keyword:

wihle ( 1 ) pollForInput();

The programmer almost surely intended the keyword

while, but the scanner can only recognize this as

an identifier. Similarly, the programmer might use an illegal

character in an identifier:

if isEven?(num) ...

The programmer may have intended isEven? as the

name of a function. However, the scanner will see that the

? is not a valid character in a name, recognize

an identifier isEven, and then try to create a

token for the question mark. If so, then the scanner will

not be able to report "invalid identifier", only "invalid

character". Or, if "?" is a valid token in the language, the

scanner will return two tokens and not report an error at all!

More generally, how should a scanner behave after it finds an error? The characters in the stream after the error may well match a pattern in state machine.

Perhaps the simplest option is called panic mode. The scanner deletes characters until it finds a match. This is surprisingly effective in an interactive setting.

Another option is to insert, replace, or delete a

character from the stream. For example, the scanner might offer

to insert a 0 after the decimal point in

1. + 2.

A third option is to transpose adjoining characters to

see if a match can be found. This would fix the misspelled

while above. +

Search engines like Google uses strategies like this in real-time when they provides spell checking on queries.

Most compilers operate on a single-error assumption and look for the one simplest change that would fix the stream. This is a common strategy when diagnosing faults in most engineered systems, and even natural systems like the human body. It works well in a compiler, too, except perhaps when working exclusively with novice programmers.

Project Check-in

What questions do you have?

Don't forget about the status check for Project 1 that is due tomorrow.