Session 4

Regular Expressions and Finite State Automata

Homework 1

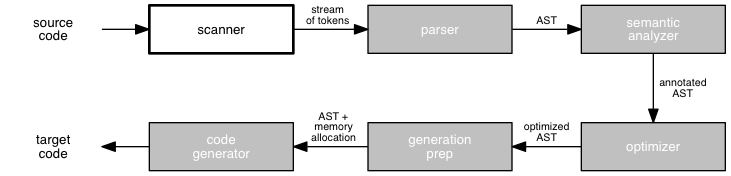

How successful have you been in re-creating the "six stages of a compiler" graphic using Dot? What do you think of it as a programming language? What do you think the compiler for it must be like?

Dot is a reminder that every data file is a program, if only we have an interpreter or compiler for it. This isn't so strange for programmers, really. Query languages such as SQL and declarative programming languages such as Prolog are not so different in concept.

I make a point on Homework 1 to ask you to submit two plain text files. I hope that it is not too surprising to you that in software development we don't use tools such as Word and formats such as PDF for the primary output of our work. Code is text.

These days, a lot of CS students seem to use VS Code. I do, too, though mostly for web development, not for general programming. (If you've read my About Me page, you know I'm an emacs man.)

If you are looking for a good text editor, this 2023 article on text editors is still pretty good. Among its recommendations are:

- on all platforms: Atom and Visual Studio Code (free), Sublime (paid, but good)

- platform-specific: Notepad++ (Windows) and TextMate (OS X)

- various IDEs for specific languages

- the classics: emacs, vim

Each team will decide on the set of tools it will use.

Opening Exercise

Write a regular expression that describes each of these languages. In each, a "number string" is a non-empty sequence of decimal digits, with leading zeros allowed.

- L1: all number strings that have the value 42

- L2: all number strings that have a numeric value strictly greater than 42

A "not" operator would be handy, but we do not have one. (And for good reason, as will become apparent soon.)

However, |

can be your friend!

Once you've done these tasks, how hard is it to extend L2 to include all number strings that do not have the value 42?

If we don't worry about creating a minimal regular expression, we can usually create something that works by trial and error. Like any other form of programming, skill at creating regular expressions comes with knowledge and practice.

Some programming languages provide more powerful notations for regular expressions than we are using. But the most important part of creating any regular expression is the thinking.

Where Are We?

Last session, we began our study of lexical analysis. The scanner's job is to transform a stream of characters into a stream of tokens, which are the smallest meaningful unit of a language. To build a scanner, we first need a language for writing rules that describe tokens.

For this purpose, we introduced the idea of a regular language. Regular languages are not a perfect match for tokens, but they are quite close. With a few lexical notes to clarify the details of a programming language, regular expressions serve us well. Regular languages can be described using BNF expressions that do not use recursion.

Once we have a language for describing tokens, we need a technique for writing programs to recognize tokens that match the rules. A program that does this task is called a recognizer. Recognizers for regular languages can be built in a straightforward way because of the language's simple structure.

Today, we will learn a tool for writing programs to recognize regular expression, the finite state automaton, or FSA. In particular, we will see that we can create a deterministic FSA, or DFA, for any regular expression.

Finite State Automata

Introduction

A finite state automaton, or FSA, is a mathematical "machine" built from states and transitions among states. +

You may recognize this as an example of a more general idea: a directed graph over a set of nodes and edges.

An FSA begins execution in its start state. At each step, it reads a character from an input string, and follows a transition to a new state.

If an FSA reaches the end of its input string and is in one of its designated terminal states, then it has recognized a member of the language it models. If the machine consumes every character of its input string and comes to rest in any state other than a terminal state, then the automaton fails, which indicates that the string is not a member of the language the FSA recognizes.

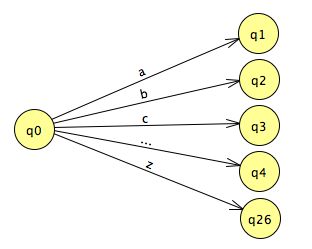

A machine might also fail by not having a transition out of

its current state that corresponds to the character it has

just read. A complete machine will have a transition

for each letter in the language's alphabet coming out of

every state. For the alphabet [a-z], this means:

The character class gives us a nice shorthand for expressing a choice in a regular expression. In an FSA, we can create a shared transition and label it with a character class.

For simplicity's sake, we do not always draw a complete transition diagram even when the machine is complete. In such a case, if the FSA reaches a state that has no transition out for the next character in the input, then it fails to recognize the input. We can think of such a state as having a transition for all of the omitted symbols that leads to an implicit dead state, which has no outgoing transitions.

An Example

Here is an FSA that recognizes the language { "if" } for the alphabet { "i", "f" }:

q0 is the start state, and q2 is the

terminal state. Note that the state state is marked with a

triangle, and the lone terminal state is marked with a double

circle. This is one convention for marking an FSA.

This is not a complete FSA diagram, because it does not have

transitions for (q0, f) or (q1, i),

or any transitions out of q2. If the alphabet of

this language contains more characters than 'i' and 'f', say

[a-z], then it is missing many

transitions. Following the convention just described,

if this FSA ever encounters a character in a state without

a transition for it, the machine fails.

If every state in an FSA has exactly one transition out for each member of the alphabet, then we say that it is a deterministic finite state automaton, or a DFA. Otherwise, it is nondeterministic, or an NFA. Our FSA for recognizing the language { "if" } is deterministic; each (state, character) pair takes the machine into a unique state.

Suppose that we would like to recognize the language from

[a-z] that consists of two- and three-character

strings that start with "if":

{"if", "ifa", "ifb", ..., "ifz"}.

We can write several different regular expressions to describe

this set, including:

-

if | if[a-z] -

if(ε | [a-z])

In regular expressions, we sometimes use ?

as a shorthand to represent an optional character. So, the

regular expression for our "if" language could also be written

if[a-z]?.

Here is an FSA that recognizes the regular language

if[a-z]?:

![a directed graph similar to the previous one, except that node q1 also has an edge 'f', leading to state q3, which is connected to terminal state q4 by edge '[a-z]]'](../images/session04/fsa02.gif)

Is this FSA deterministic or non-deterministic?

This machine has two terminal states, q2 and

q4. It is nondeterministic because it has two

transitions out of state q1 on the symbol

f: one to q2 and another to

q3.

Quick Exercise: Can you create a deterministic FSA to recognize this language?

How about this:![a directed graph similar to the previous one, except that node q1 also has an edge 'f', leading to state q3, which is connected to terminal state q4 by edge '[a-z]]'](../images/session04/fsa02-dfa.png)

Converting a Regular Expression to an FSA

There are a number of techniques for converting a regular

expression into a DFA. All start with the idea that each

character in a concatenation is a transition between states.

Repetitions can reuse the previous state, unless they change

the state's status as terminal or non-terminal. Consider

abc and

ab*c.

A choice branches to different states, which can then converge

back to a common state. Consider

a(e|f)c.

We'll consider more complex regular expressions next time — and take advantage of non-determinism.

FSAs and Regular Languages

The language recognized by an FSA is the set of strings that leave it in a terminal state. It turns out that the language accepted by any FSA can be written as a regular expression. A theory of computation course such as CS 3810 often teaches a nice proof of this relationship. Even without a proof, though, we can see that it is possible to create a "regex" for any machine by simulating it: walking through the states, step by step, and producing a sequence of sub-expressions along the way.

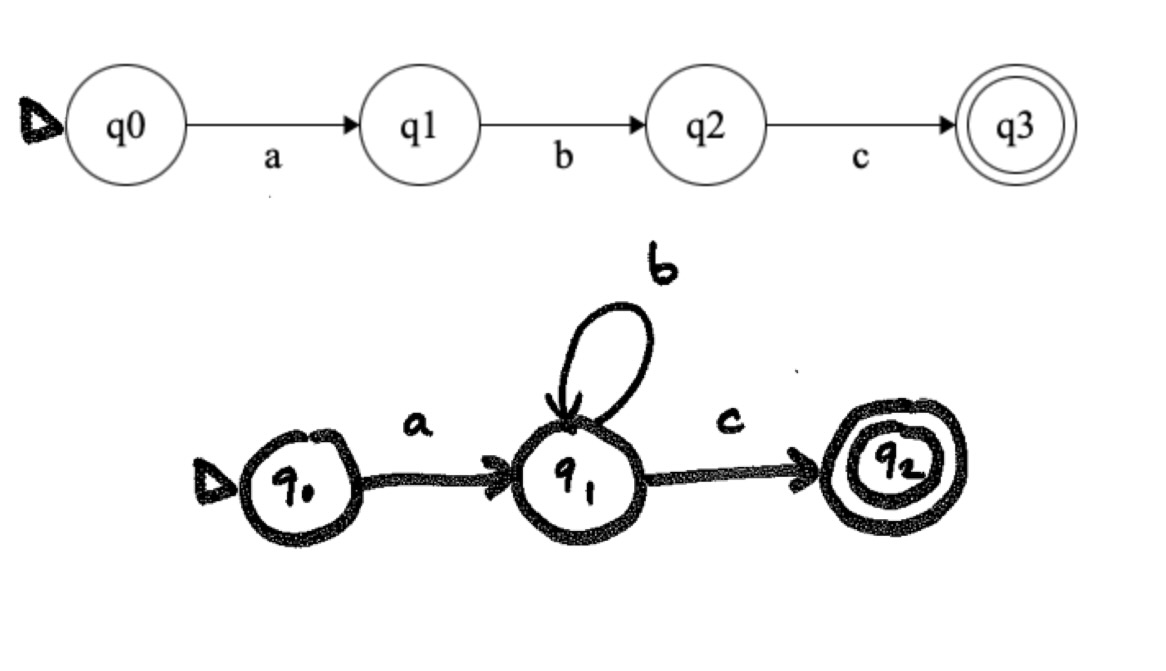

Consider this DFA:

We can walk down its states to see that the language recognized

is described by the regular expression

a(x{,x}).

Note that the parentheses in this expression are part

of the language's alphabet. That means we can't use them for

grouping purposes in the BNF syntax of our regular expression.

Instead, I have used the grouping shorthand

{} to indicate 0 or more repetitions. We

could also write this regular expression with quoted literals

as:

"a(x" · (",x")* · ")"

... but that's a bit difficult to read even when using different colors.

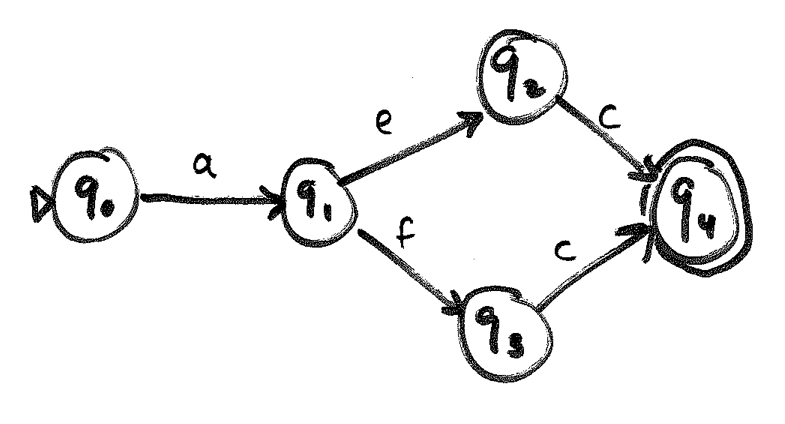

Quick Exercise: Now try it for yourself. Convert this DFA to a regular expression:

This one is tougher, because it has two loops, and thus two repetitions, one nested within the other. But we ought to be able to derive this regex:

a{+{c*}b}.

... by walking the FSA and adding loops as options one at a

time. Again, note that the * and the

. are part of the language's alphabet; their use

here does not indicate repetition or concatenation. The period

in the language also makes it a bit difficult to use this regex

clearly within a paragraph.

As you can see from only a couple of examples, the process of converting a deterministic FSA into a regular expression is relatively straightforward. It should not surprise you that we can write simple programs to automate the process!

Even better, the structure of tokens in a programming language is usually considerably simpler than the puzzle-like regexes and FSAs that we have seen today. That means the basic FSAs we need to create for our scanners will be simpler and easier to work with.

The fact that we can write a regular expression for any deterministic FSA means that the set of languages recognized by FSAs is a subset of the set of regular languages:

FSA ⊂ RL

In the section Finite State Automata, we created FSAs for several simple regular expressions. We can create a deterministic FSA for any regular expression. This means that the set of regular languages is a subset of the set of languages recognized by FSAs:

RL ⊂ FSA

Together, these two relationships tell us that the set of regular languages is identical to the set of languages recognized by DFAs!

The second relationship here is important for those of us who want to write a compilers. It means that any regular expression can be recognized by an FSA. Why is this so good for us? Because then we have a clear path to writing a scanner:

- Describe the tokens in a language using regular expressions.

- Convert the regular expressions into DFAs.

- Write a program that implements the DFAs.

We will explore this path further next session.

The Project

Today, we launch our compiler project for the Klein programming language. Your first assignment for the project is to write a scanner for Klein and then use it to process some Klein programs.

Topics for discussion now:

- implementation languages

- tools: IDEs, version control (git and gitlab), testing

- project management

- source language spec

- sample programs

Teams meet. Have conversations that lead to:

- scheduling regular times to meet

- electing a team lead

- selecting an implementation language

- selecting a toolset

- creating a team name

Please email me the name of your team and who will be the team lead.

Once you have decided on a version control system and tools, you can create your repository and use it to maintain your team's documents. Hold off on writing code for a few days, though. There is no hurry. A few other tasks come first:

- Task 1 is to begin learning Klein.

- Task 2 is to identify the various kinds of tokens it allows.

- Task 3 is to describe each kind of token with regular expressions.

- Task 4 is to convert the regexes to DFAs, which we will talk more about next time.

Compiler Moments: The Purpose of a Compiler

This is probably a good moment to think about this passage:

There's the misconception that the purpose of a compiler is to generate the fastest possible code. Really, it's to generate working code -- going from a source language to something that actually runs and gives results. That's not a trivial task, mapping any JavaScript or Ruby or C++ program to machine code, and in a reliable manner.

That word any cannot be emphasized enough.

This is the opening salvo in an essay on the "madness" of optimizing compilers. We may not have a chance to implement many optimizations into our compilers this semester, but we will learn some techniques that enable an ordinary compiler to do a pretty good job. Do keep in mind, though, that your compiler must work for any Graphene program we throw at it.

This may sound daunting now, but the techniques you learn will prepare you to write such a compiler in a reliable manner. Work together carefully, and you will make steady progress toward the goal!