Session 2

A Simple Compiler

Where Are We?

Last time, we considered a compiler first as a black box and then as two-stage process of analysis and synthesis. We then decomposed the process into six generic stages and walked through each component in just enough detail to get a sense of what sort of processing each stage performs. That discussion described what a compiler does, but not how it works.

Today we turn our attention to how a compiler does its job and look at the complete implementation of a simple compiler. In preparation for our discussion, you read the README for the compiler, which included

- the grammar for the source language,

- sample source programs and instructions for generating target programs, and

- a high-level view of the program's architecture.

and then studied the code for the compiler itself. Be sure to ask questions as we discuss the compiler now.

In today's discussion we may see ideas that are new to you. Don't worry that you don't understand them all yet. The goal of today, as last time, is to give you a broad sense of the ideas and issues we will deal with throughout the course. Beginning next time, we begin our deep dive into the first stage of the compiler.

A Simple Compiler

Introduction

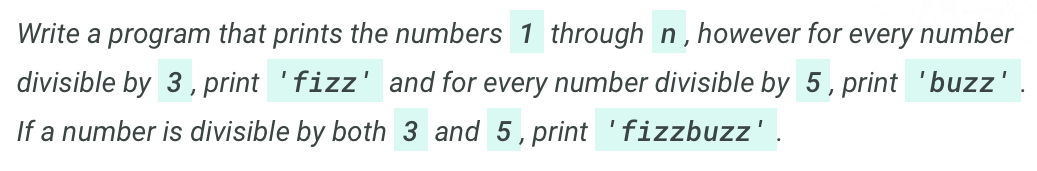

This compiler was motivated by an article called "The Fastest Fizzbuzz in the West" (no longer on the web), in which the author defined a new language, Fizzbuzz, that he could use to solve the mythical interview question of the same name:

The idea is this: why keep writing Fizzbuzz over and over? We write a program in the new language:

1...15 fizz=3 buzz=5

We compile this program to target code that generates the desired output. But, with a new programming language, we can solve any variation of the problem in just a few lines of code. In the mythical interview, you can also demonstrate just how much computer science you know.

I decided to write a compiler for Fizzbuzz in standard Python. The result is a compiler that is simple enough to read in one sitting but complex enough that it can also be used to demonstrate more sophisticated techniques throughout the course. For today, I asked you to study this compiler. The starting point for your study was the README file.

The source language, Fizzbuzz

A Fizzbuzz program consists of two parts: an integer range and a sequence of word/number pairs. As a result, the language has only a few features:

- two data types, integers and words, and

-

two operators,

=and...

Here is the grammar of the language, as defined in the README file:

program ::= range assignments

range ::= number ELLIPSIS number

assignments ::= assignment assignments

| ε

assignment ::= word EQUALS number

word ::= WORD

number ::= NUMBER

The ε indicates nothing, an empty string. NUMBER, WORD, EQUALS, and ELLIPSIS are all terminals that correspond to the items described informally above.

The target language, Python

The compiler generates standard Python code. For now, this shields us from having to learn details of a lower-level target language, but it also hides from us some of the beauty of a more complex code generator. Fortunately, the semantics of the Fizzbuzz language make it possible for us to explore lower-level concepts later in the course.

Going Deeper with the Compiler

The Fizzbuzz program to play the canonical Fizzbuzz game looks like this:

1...15 fizz=3 buzz=5

We compile it in this way:

$ python3 compiler.py programs/default.fb

... to produce this Python program:

for i in range(1, 16):

output = ""

if (i % 3) == 0:

output += "fizz"

if (i % 5) == 0:

output += "buzz"

if output == "":

output += str(i)

print(output)

We execute the compiled program directly like this:

$ python compiler.py programs/default.fb | python

Or save the generated code to a file and run that file:

$ python compiler.py programs/default.fb > fizzbuzz.py $ python fizzbuzz.py

One way to study Fizzbuzz's syntax of in more detail is to use its grammar to derive the program defined in the source code:

program range assignments number ELLIPSIS number assignments NUMBER ELLIPSIS number assignments NUMBER ELLIPSIS NUMBER assignments NUMBER ELLIPSIS NUMBER assignment assignments NUMBER ELLIPSIS NUMBER word EQUALS number assignments NUMBER ELLIPSIS NUMBER WORD EQUALS number assignments NUMBER ELLIPSIS NUMBER WORD EQUALS NUMBER assignments NUMBER ELLIPSIS NUMBER WORD EQUALS NUMBER assignment assignments ... NUMBER ELLIPSIS NUMBER WORD EQUALS NUMBER WORD EQUALS NUMBER assignments NUMBER ELLIPSIS NUMBER WORD EQUALS NUMBER WORD EQUALS NUMBER

For the rest of this session, let's turn our attention to the implementation of the compiler. You can follow along in the Python source code. This implementation is proof that a programmer can hack up a compiler for a simple language in relatively short order. It is not the best coding example, but it is a simple example to get us started.

Some things to note about the structure of the compiler:

-

It consists of four stages, not six.

-

There is no optimization stage.

(What would that look like for Fizzbuzz?) -

There is no preparation for code generation.

(Fizzbuzz is simple, and Python is a high-level target.)

-

There is no optimization stage.

- It uses two supporting data structures (token and AST nodes), with another embedded in the code (symbol table).

- This compiler is parser-driven: it speaks only to the parser and never to the scanner. The parser asks the scanner for tokens as it needs them.

-

The compiler contains a set of custom error classes, which

give it...

- the ability to provide typed error messages

- the ability to extend errors with more content, behavior

-

Finally, there is a decent set of unit tests, using PyUnit.

-

It's all talk until the tests run.

— Ward Cunningham, a progenitor of JUnit, design patterns, and wiki. - They are executable documentation.

-

The Token Class

The job of the scanner is to transform the stream of raw

characters that make up a Fizzbuzz program into a sequence of

tokens. We define

a Token data structure

to support the interface between the scanner and the parser.

Our compiler has unique tokens for each of the two operators, both kinds of value, and an end-of-file marker. The last is a convenience for processing the input downstream from the scanner.

A token is implemented as a pair, or more generally a tuple, consisting of:

- type — a flag (a named enumeration)

- value — one of three possible (integer, string, or none)

Here are some thoughts I have about this implementation:

- using enumerations for simple named types

- blurring identity and value

- the filename...

The Scanner Class

An instance of this class turns numbers and individual characters into tokens.

Why bother? My parser would be almost as simple without the scanner, and the data being processed would be more compact. One reason is separation of concerns. If we want to broaden the concrete syntax of Fizzbuzz — say, to allow more kinds of characters in identifiers — we can modify the scanner and token classes without having to modify the parser, which deals with syntax and is complex enough on its own.

Another is pluggability. Next week, we will learn how to write a cleaner, sounder scanner. When we do, we can plug our new scanner into the Fizzbuzz compiler, and it will work.

The public interface of

the Scanner class

consists of two methods. nextToken() is the

primary method by which the parser requests the next token. The

scanner also allows the parser to peek() ahead to

the next token without consuming it, as a convenience. This

implementation uses a Token instance variable to

hold the "peeked" token and return it when requested via a

nextToken() message.

Why might the parser want to peek() ahead? We'll

see soon!

The helper method getNextToken() is the function

that actually reads a token. Some implementation notes:

- Some of the tokens are literals and can be recognized as one or three specific characters. The rest need to be built one character at a time until we reach a delimiter.

-

We need

is_whitespace(char)because the standard methods in Python allow other non-visible characters, such as Unicode, which are not allowed in Fizzbuzz's specification.

getNextToken() and its helpers are written in an

"ad hoc" fashion, that is, without following any formal

mechanism. But they were written in a principled way, following

the pattern of the regular expression for Fizzbuzz tokens. For

more complex grammars, we will want to use the regular

expression in a more formal way. Consider even the relatively

simple case of the + and ++

operators...

Another reason to write a scanner is that we can use it

independent of the parser. To help us visualize the token

stream in a Fizzbuzz program, I wrote a little program called

print_tokens.py.

It does nothing more than create a scanner, ask it to produce

the tokens in a program, and print them. This program helps

us see that our scanner is doing what we expect it to do!

The AbstractSyntaxTree Class

The job of the parser is to determine whether a stream of tokens

satisfies Fizzbuzz's grammar. In doing so, it transforms the

token stream into an abstract syntax tree. We define

an AST_Node

data structure to implement the output of the parser.

If you have studied programming languages, you may recall that we will define one element of abstract syntax for each arm of the language grammar that has semantic content. For Fizzbuzz, this includes a program, a range, and an assignment.

Quick Question: I use a list of assignment nodes to represent an "assignments" node, rather than make a separate class for the collection. What trade-off does this make?

Each of these elements captures only the essential information

in the corresponding part of the source code. For example, an

Assignment_Node does not need to record the

character = that separates the word and its number,

because that is implicit in the element itself. It does need

to record the word being declared and its associated number,

because they vary from one Assignment_Node to the

next.

Some implementation notes:

-

The public

AST_Nodeclass serves as a generic type for all ASTs. It is an abstract superclass that allows our compiler to operate on anyAST_Nodewithout knowing its concrete class. - There is one (hidden) class for each element type. These classes record the essential information about each semantic element in the program.

The Parser Class

The parser transforms individual tokens into meaningful elements of the program, represented as a tree.

In general, we construct parsers guided by the language grammar. There are a number of techniques for doing this, each working for a particular set of grammars. Fizzbuzz's grammar is quite simple, but it is representative of the grammars for many languages that are more complex. The Fizzbuzz compiler uses a standard technique for processing grammars of this type, known as recursive descent.

A recursive-descent parser descends through the derivation tree that it recognizes as it examines tokens, making recursive calls to recognize sub-elements. We write one parsing procedure for each non-terminal in the language grammar.

For Fizzbuzz, this means that we will write a parsing procedure for a program, a range, a set of assignments, and so on. Each of these procedures recognizes a non-terminal of the corresponding type by determining whether one of the non-terminal's rules matches the sequence of tokens being processed.

To implement a parsing procedure in this way, we can write:

- a conditional statement to determine which grammar rule to apply, and

- code to recognize the elements on the right-hand side of the selected grammar rule. This can match terminals directly but must recur on non-terminals.

The only grammar symbol in Fizzbuzz that requires a conditional

choice is assignments, which can match a single

assignment or end-of-file.

Our example program above illustrates all of the key features of recursive descent, including peeking ahead to see that a list of assignments has ended.

The reason the parser peeks ahead is that, in recursive descent, a parser must never backtrack, because it doesn't remember where it came from or what state it was in there. Whenever two rules might apply, it must be able to predict correctly which rule does apply. For this reason, the ε arms of the grammar can create a challenge.

Fizzbuzz's parser solves the ambiguity problem by looking ahead

one token, using the scanner's peek() method. A

compiler might look ahead more than one token, but that is

extremely rare in practice. Other parsing techniques support

backtracking, with the trade-offs on performance that you might

expect.

If the parser encounters an illegal or otherwise unexpected

token in the stream produced by the scanner, it generates a

ParseError. More generally, a parser throws an

exception whenever it cannot find a production rule in the

grammar that matches its input.

My approach to building the parser was somewhat ad hoc, which works fine for a small, simple grammar. In this course, we learn several principled approaches for building parsers that scale better to larger, more complex languages.

Semantic Analysis

The analysis phase of a compiler ensures that the program conforms to the language's definition. The various stages of analysis approach this problem at different levels.

Scanning verifies the program at the lexical level, in terms of characters and meaningful "words". Parsing verifies the program at the syntactic level, in terms of the program structures defined in the grammar. Each of these steps works locally, examining only adjacent elements as defined by the definition of tokens and the grammar of the language.

Semantic analysis verifies any element of the language definition that applies across structures. We can think of it as a global validation of the program. Semantic analysis typically deals with issues of declarations, scope, types, and type-specific operations, including issues with operator overloading. These all deal with consistency among parts of the program.

For Fizzbuzz programs, semantic analysis must verify that

- the range makes sense,

- the assignments use legal numbers, and

- the words are unique.

The first two of these tasks are done by the

TypeChecker itself, while the third is assisted by

the creation of a symbol table.

The Type Checker

The

TypeChecker

examines each node in the AST to ensure that it makes sense

in the context of the other nodes.

The Symbol Table

The symbol table is a Python dictionary. It allows us to find out if a word is used in more than one assignment statement. In more complex compilers like the one you build this semester, later stages will use the symbol table to do substantial work, in particular during register allocation and code generation.

The CodeGenerator Class

After the type checker ensures that the program satisfies the

type rules of the language and builds a symbol table,

CodeGenerator

is ready to transform the annotated abstract syntax tree into

code in the target language.

In many compilers, actual code generation is preceded by a step that allocates registers to specific variables and expressions and creates a memory map for program values. However, this compiler produces Python target code, which allows the code generator to work at a much higher level.

The public interface of a code generator consists of a single

method, generate(ast, symtable). This method

generates code in three parts:

-

a prologue that produces the control line of a

forstatement, - a "middle" that produces the various cases of the Fizzbuzz printer, and

-

an epilogue that produces the

printstatement that finally generates Fizzbuzz's output.

The last of these is simple enough to do in place; the first two

are implemented in the helper methods

generate_prolog() and generate_cases().

Some implementation notes:

-

generate_cases()generates the most lines of code as it creates anifstatement and iterates over the list assignments to create its cases. -

The various

generate_*functions use templates to create the target code they are responsible for. For a more complex target language, we might want to have a more sophisticated way to select and instantiate the code templates, or perhaps not use templates at all. -

In a more object-oriented implementation, the classes for

our tree nodes,

Program_Node,Range_Node, andAssignment_Node, might havegenerate()methods to generate code for themselves. This would decentralize code generation to the point that our code generator class would serve only as a bridge between the compiler and the objects that generate the code.

Wrap Up

There it is: an entire compiler, from beginning to end, in one session. It is simpler in almost every way from a compiler for a more complete source or target language, yet it is complex enough to reward real study. Please ask any questions about what this compiler does, how it does it, or why.

This concludes our introduction to the course. We are ready to move on to consider each of the stages of a compiler in much more detail — and how to write one. Next session, we begin at the beginning, with lexical analysis.

Note that Homework 1 will be available soon. A quick note about submission...

- I ask for two "plain text" files.

- The assignment will be due at 11:59 PM.

- Try to submit early, and feel free to re-submit at any time, The system will overwrite an existing file with the new file.

We will talk more about the project next week, including project teams. A quick note on implementation languages and on working with a team:

- teammates (confidence)

- commitment

- investment

- working together: meetings, (a)synchronous, pairing