Session 3

Lexical Analysis and Regular Languages

Where Do the First Compilers Come From?

Last week

we spoke of a compiler as a program that translates one program,

written in a source language, say S,

into another program, written in a target language,

say T.

The compiler itself is a program, too, so there is actually a

third language involved: the language in which the compiler is

written. We call this the implementation language,

say I, of the compiler. This language

characterizes the platform on which the compiler runs.

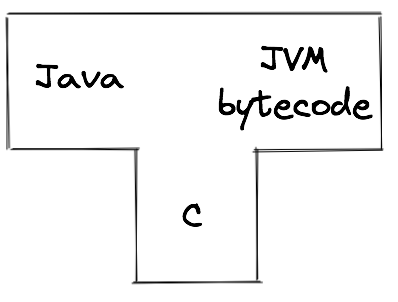

For example, when you compile a Java program using javac, you are using a compiler whose source language is Java and whose target language is JVM bytecode. The implementation language is C — that is, javac itself is written in C. The program javac has to be compiled using a C compiler to produce machine language before it can be executed.

This semester, you and your teammates will write a compiler whose source language is Klein and whose target language is TM. You will choose the implementation language, say, Python, Java, Racket, or C, based on the team's skills and background. (More on all of these languages later.)

My sentences describing these compilers are a bit wordy. We can represent a compiler as a triple of source, target, and implementation languages in more concise ways. Computer scientists love a good notation, so they invented the T-diagram. The T-diagram for the standard Java compiler is:

For the compiler you write this semester, we have this T-diagram:

T-diagrams can help us visualize some of the interesting ways in which compilers are created using a small number of tools. Consider this common student question, which one of you asked last week on one of the surveys:

Where did the first C compiler come from?

You might ask the same question of Java or Ada, but C is the "base case" in our usual devolution toward the machine: most industrial compilers are written in C, including most C compilers themselves!

Here is how we bootstrap the first native C compiler. First, we identify a minimal subset of C, called C0, that is Turing-complete. We use assembly language to write a compiler from C0 to assembly language:

Then we write a compiler for C in C0:

Finally, we compile the second compiler using the first:

If we now want a native C compiler written in full C, that is, C→ASM(C):

... we write it, and compile it using our native C compiler.

We can use a similar technique to bootstrap an optimizing compiler that optimizes itself. Huh? Follow the T-diagrams...

First, of course, we write an optimizing compiler for S in S that compiles to machine language M, S→M(S).

Then we write a quick-and-dirty native compiler that translates S into M. For all we care, both the translation process used by the quick-and-dirty compiler and the code it generates can be of low quality. We can refer to these "quick-and-dirty versions" with M*: S→M*(M*).

Finally, we compile our S→M(S) compiler twice:

- first, using our quick-and-dirty compiler, and

- second, using the compiler produced by our quick-and-dirty compiler!

Look at that second step: The optimizing compiler optimizes itself! Beautiful.

Transition, From Breadth to Depth

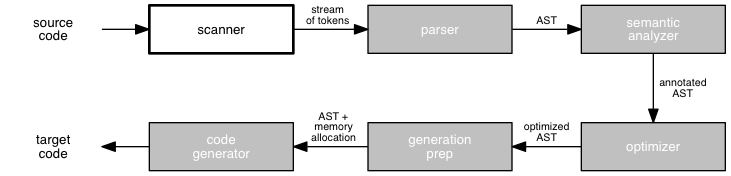

Last week, we looked at the idea of a compiler from a high level and then studied a complete compiler, from end to end. We were able to see most the phases of a compiler implemented, but only for a simple language that constrained the decisions that we had to make. This study gave us breadth into how a compiler works, but only a little depth.

For the rest of the semester, we will examine each of the phases of the compiler in much more depth. We begin at the beginning, with the scanner. This is the module of the compiler that performs lexical analysis.

Digression: Would it make any sense not to begin at the beginning? Could we begin at the end? Could we cover the entire problem every week? There might be advantages to a different approach.

Lexical Analysis

The job of the lexical analyzer, or scanner, is to transform a stream of characters into a stream of tokens. The token is the smallest meaningful unit of a language.

A scanner needs to know how to recognize the terminals in our language grammar: the keywords, the punctuation marks, the identifiers, and the literal values of every type. We know the exact form of keywords and punctuation, so our scanner can recognize them with a perfect match. Identifiers and values, though, are defined by rules that tell us how to match an input string with one of these terminal types.

The scanner also needs to know how to recognize the characters that don't matter, such as whitespace. Most languages define whitespace as insignificant, at least in most places. Programmers use it to make a program easier to read, but it does not contribute to the meaning of the program.

There are some potential conflicts. What if a program contains

the string "if8"? Is it an identifier, or the

keyword if followed by a number? The language

definition should cover such cases, and the scanner for the

language must implement this specification.

To build a scanner, we need:

- a language for writing rules that describe tokens

- a technique for writing programs that recognize tokens matching the rules

We will use regular expressions as our language for writing the rules that describe tokens and deterministic finite state machines as our technique for writing programs that recognize tokens described by these rules.

These techniques may sound scarier than they are. CS theory will help us to develop these techniques and show us that we can directly convert our description of rules into code that recognizes tokens.

Languages and Notation

An alphabet is a finite set of symbols. For example,

{a, b, c, ..., z} ∪ {A, B, C, ..., Z} is

the Roman alphabet that we use for words in English.

{0, 1} is the usual binary alphabet.

A string (or word or sentence) is a finite sequence of characters drawn from from an alphabet. "Vonnegut" is a favorite string of mine from the Roman alphabet. "01111111" is a word in binary. Both of these strings have a length of 8. Not all strings have length 8, of course. "Kurt" and "1001001" are other strings drawn from these alphabets; "chronosynclastic" is another favorite of mine. There is even a string of size 0, "", that can be drawn from any alphabet. We will refer to it with the symbol ε, the lowercase Greek letter epsilon.

A language is set of strings drawn from a particular alphabet. {"Kurt", "Vonnegut", "chronosynclastic"} and {"01111111", "00", "1001001"} are languages over the Roman and binary alphabets, respectively. ε can be a member of a language, too, so {"Kurt", "Vonnegut", ε} is a language. Finally, the empty set {} is a language, too. We will often denote it with the symbol ∅.

Unlike a string, a language can be infinite. We can't write down all of the members of an infinite language, obviously. If we want to specify it, we need a notation that describes the members of the set.

In computer science, we typically use BNF notation to describe the strings that make up a programming language. Here is a BNF description consisting of two rules for a language drawn from the alphabet {a}:

S ::= A

A ::= aA

| ε

This definition describes the language

{"", "a", "aa", "aaa", ...},

the set of strings that consist of 0 or more a's.

It is an inductive definition, because the

non-terminal A is defined, in part, in terms of itself. We can

also describe this set using a single BNF rule:

S ::= a*

that uses the character * to indicate zero or more

repetitions.

In a BNF description:

- symbols stand for themselves in strings,

|indicates a choice,*indicates a repetition,.indicates a concatenation, and- ε indicates the empty string.

If the same symbol is both a non-terminal in the grammar and a

member of the alphabet, we can use quotation marks to indicate

the string explicitly. So, if lower-case a is

also a grammar symbol, we might write "a"A

instead of aA.

A choice is often called "alternation". We can express choice with separate rules:

A ::= aA A ::= ε

but the | operator makes it easier to keep the

alternatives together in space and to see the choice. We can

pronounce the bar as "or".

A concatenation is often indicated by juxtaposition, that is,

simply by placing two symbols next to one another. This is

how the grammar above shows concatenation in its second rule,

aA. Grammars often use the

. symbol ony when juxtaposition causes a

problem reading the grammar.

Whenever we use a non-terminal on the right hand side of a production, we are saying that it can be replaced with any string that matches the non-terminal. This allows us to write inductive definitions of strings, which is the source of much of the power of BNF notation.

BNF notation is useful for defining programming languages because, as described here, it is capable of defining context free languages, a set of languages to which many programming languages belong. We will use BNF for this purpose (to describe the syntax of our programming languages) when we move on to the topic of parsing in a few sessions.

However, the tokens that a scanner recognizes almost always form a simpler kind of language called a regular language. Regular languages are a subset of the context free languages whose definitions contain no recursion, only repetition. Let's turn our attention to regular languages and how to recognize them.

Regular Expressions

A regular expression is a description written in the notation described above, but with no recursion. For example, consider identifiers in the language Pascal, which consist of letters, digits, and underscores up to 1024 in size, but which must begin with a letter. A regular expression for these identifiers is:

identifier ::= letter (letter | digit | "_")*

Note that the regular expression does not incorporate the 1024-character maximum length (nor a further restriction that the first 255 characters of any identifier be unique). As originally defined, BNF notation does not allow us to express this kind of condition. We could extend BNF to allow it, but that would result in BNF descriptions that are harder to read. Instead, we usually identify length restrictions outside of the language grammar, in a text description. This allows us to write simpler BNF descriptions for strings of unbounded length.

Of course, letter and digit are

non-terminals, so technically we should define them, too:

letter ::= a | b | c | ... | z | A | B | C | ... | Z digit ::= 0 | 1 | 2 | ... | 9

You will commonly see BNF descriptions that leave some non-terminals undefined, relying on a common understanding of their meaning. But a formal language specification must include them.

Now try your hand at it...

Quick Exercise: Write a regular expression to describe the set of non-negative integers as they are commonly written.

Here is a solution that fails. Why?

integer ::= digit*

Well, for one, it says that the empty string is an integer! It also allows for 0 and 00 and ..., which all presumably refer to the same value, zero. Leading zeros are not part of how we commonly write numbers. We need to treat zero separately and ensure that non-zero numbers start with a non-zero digit. So perhaps:

integer ::= 0 | nonzerodigit digit* nonzerodigit ::= 1 | 2 | ... | 9 digit ::= 0 | 1 | ... | 9

This simple little language shows us something important: Defining a language, even a simple language, requires attention to detail.

Writing out a full set of choices among alphabetic or numeric

characters is tedious and not helpful to human readers, who

know these sequences well. So we often use square brackets,

[], to denote a character class.

[] gives us a shorthand for indicating a choice

from the class. With this shorthand, we can describe

non-negative integers more concisely as:

integer ::= 0 | [1-9][0-9]*

Notice that we have added two more characters to the language

of regular expression notation. What happens if [

and ] are characters in our alphabet and we want

to include them in a character class? We need a way to

distinguish the alphabet character [ from

the regular expression character [.

As noted above, we can quote the brackets: "[" and

"]". With typography, we can use a different

typeface, type size, or decoration such as bolding,

[ and

], if that

makes the character sufficiently distinct to readers. (Can

you see the difference on the web page?)

In plain text computer languages, we often escape the

literal character, using a special character. In most

Unix-based regular expressions,

\

is the escape character. For example, we could describe the

language {"[1]", "[2]", ..., "[9]"} as

\[[1-9]\]

(Yes, that makes my head hurt, too.)

Try your hand at another regular language:

Quick Exercise: Write a regular expression to describe the set of identifiers in some language, say, Java, Python, or Racket.

For Java, we might write...

identifier ::= javaLetter (javaLetter | digit)* javaLetter ::= letter | _ | $

Note a few things about Java identifiers:

-

In Java,

lettercontains not only the standard English letters but also many Unicode alphabetic characters, including such as ü, ß, Ñ, and ñ. To describe these characters, we need a new rule or character class. - A Java identifier is defined as an "unlimited-length sequence", so there is no need for a semantic note outside of the grammar to limit the length of strings described by our regular expression.

-

A Java identifier cannot have the same spelling as a Java

keyword (say,

publicorfor) or reserved literal (true,false, andnull). In such languages, the specification for the language must say so.

In practice, a Java scanner will recognize reserved words prior to trying to match an identifier. So it does not have to worry about subtracting reserved words from the set of identifiers it matches. This is an example of pragmatics, the nuts-and-bolts elements of writing descriptions and programs that lies outside the formal definition of BNF.

Note, too, the use of parentheses, (), for

grouping in the rule that defines identifier. Like

the [] pair used for describing character

classes, they are not part of the identifier.

Here is one you can try at home:

Quick Exercise: Write a regular expression to describe the set of comments in some language, say, Java, Python, or Racket.

Regular expressions are useful to us in this course for a couple of reasons. First, they match the notational needs of lexical analysis quite well, which enables us to write concise and clear rules to describe the identifiers and values in a language. Second, it is relatively easy to write simple, efficient programs that recognize regular expressions.

In computer science, you will see this pair of ideas appearing together frequently: a notation for describing something, and a technique for writing a program to recognize that something. You might think about BNF as a language, and what it would take to write a program to recognize and process BNF descriptions.

The regular expressions we write should be:

- complete: match any legal sequence of characters

- sound: match only legal sequences of characters

- unambiguous: give a definite answer for any input

Handling Ambiguity

We alluded to the ambiguity problem above in the context of Java identifiers and keywords. Consider this grammar:

token ::= keyword | identifier | integer | ... keyword ::= if | ... identifier ::= javaLetter (javaLetter | digit)* javaLetter ::= letter | _ | $

Is the string "if8" an identifier of length 3,

or the keyword if followed by (the beginning

of) an integer?

Some languages are defined such that the presence or absence

of whitespace matters, which helps us to make this choice.

If keywords must be followed by whitespace, then

"if8" must be an identifier.

Other languages resolve such a conflict by including a rule

for how to match rules(!). One such rule-matching rule is

first rule to match, which makes the order of the

rules in the BNF description significant. Using first

rule to match, if8 is the reserved word

if followed by (the beginning of) an integer.

Another common rule-matching rule is longest match,

which returns the token type that matches the longest sequence

of characters. Using longest match, if8

is an identifier.

Programmers don't generally have the language grammar with them all the time, so using the first rule to match approach can create problems. Most common languages these days use the longest match meta-rule.

Next Step: Finite State Machines

Once we have a description of a language, we need a way to determine whether a given string is in the language or not. A program that does this task is called a recognizer. Recognizers for regular languages can be built in a straightforward way based on their simple structure. The technique we use is to convert a regular expression into a finite state machine. In CS theory, a finite state machine is often called a finite state automaton, or FSA.

Next time, we will learn about FSAs and how to create them.

The Project

This project requires you and me to make a lot of decisions. Some of my decisions come before the course begins, in order to make preparing the rest of the course more manageable.

What source language should we use? A "real programming language", or one created for a course? One the professor assigns, or one the students choose — or design?

What target language should we use? A "real machine language", or one created for a course? A real machine, or a virtual machine?

What implementation language should you use? One the professor assigns, or one the students choose? One every team member knows, or one a team member wants to learn in the course? A "real" compiler language, or any language that can get the job done?

What teams should work together? One, two, three, four, ... per team? Teams assigned by the professor, or teams of the students' choosing?

What tools will you use? For writing and compiling code? For version control? For testing? For documentation?

In all of these decisions, there are trade-offs. We will try to find a balance that works both for you and for me.

This project accomplishes several goals. It is the project that makes this a "project course", which means something particular in our curriculum. It is an applied exercise in software engineering, the building of large, reliable programs. Like much software engineering in the world, it is performed in a team.

Working in teams on such a large, long-lived project will be new to many or most of you. My net-friend David Humphrey wrote a great post on teaching open source software. I think one of his passages can be adapted quite nicely to team projects:

[A project course] gives students a chance to show up, to take on responsibility, and become part of the larger community. Having the opportunity to move from being a user to a contributor to a leader is unique and special.

When you work as a team, your decisions affect not only yourself but also your teammates. This requires a different kind of commitment than a regular assignment or course. It rewards the investment you make in communication and tools.