Session 5

From Regular Expressions to DFAs

Where Are We?

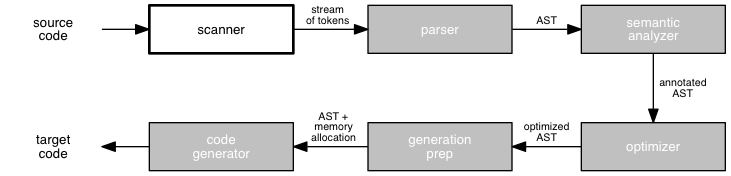

We have begun to examine the phases of a compiler in depth, beginning with the scanner. To build a scanner, we need:

- a language for writing the rules that describe the structure of tokens, and

- a technique for writing programs that recognize tokens using such rules.

For these purposes, we are using regular expressions and deterministic finite state automata (DFA), respectively. Last time, we learned a bit about deterministic and nondeterministic FSAs and how they relate to regular expressions. Today, we will learn a technique for converting regular expressions into DFAs.

Opening Exercise

Last week

we wrote a regular expression for non-negative integers:

0 | [1-9][0-9]*.

Create a deterministic FSA that recognizes these integers.

If that seems too easy, try: [0-9]*0.

Solution

"Walking down" this expression allows us to build a complete FSA without much trouble at all:

![an FSA that recognizes 0 | [1-9][0-9]*](../images/session05/regex-to-fsa01.gif)

You can imagine how easy it is to implement a piece of code to recognize strings in this language. Following the FSA may seem like overkill when processing such a simple regular expression, but it ensures completeness. Knowing how to do so is also a useful skill when implementing recognizers for more complex languages, because the technique scales well as expressions get larger.

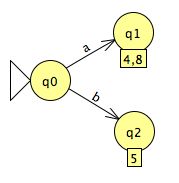

Here is

my DFA

for [0-9]*0. It's a lot easier to create

a non-deterministic machine for this expression. If

only we had a technique for converting DFAs to NFAs...

For a little fun and practice at home, do the same for some of the other regular expression we created last week.

Converting Regular Expressions into Deterministic Finite Automata

We closed last time with several claims, two of which were:

- any regular expression can be recognized by a deterministic FSA, and

- this is good for us as compiler writers.

Why is this good for us? Because it means we have a clear path to implementing a scanner, a program that recognizes tokens in a language.

- Describe each token with a regular expression.

- Convert each regular expression into a DFA that recognizes the same language.

- Write a program that implements the DFAs in code.

We learned about Step 1 last week. We learned a bit about Step 2 last week and will learn more today. You probably have some skills for Step 3 from your previous programming experience, which we will augment later today and next time with some pragmatic discussions. One of the best ways to learn about programming is by writing a big program that does something real.

For most complex token sets, we break Step 2 above — converting each regular expression into a DFA — into two steps:

- Convert the regular expression into an NFA.

- Convert the NFA to a DFA.

We do this for two reasons:

- It is often easier to translate a regular expression into an NFA than into a DFA. This is true for complex tokens and especially true when we have a choice among many different kinds of tokens, as is the case for most programming languages. Creating an NFA makes our lives easier, because both choices within a token and choices among tokens can be represented as nondeterministic moves out of a state.

- We can convert any NFA into a DFA. Computer science theory tells us any language that can be recognized by a nondeterministic FSA can also be recognized by a deterministic FSA. Today we will learn a technique for converting an NFA into a DFA that demonstrates this. As with most design and implementation choices we make, there is a trade-off between NFAs and DFAs, involving the speed and size of the resulting machines.

The three-step process outlined above gives us a repeatable, if tedious, technique for implementing token recognizers. Fortunately, we will have some tool support for doing some of the tedious conversion. Of course, this tedium is a sign that we could look for a way to automate the process. The simplicity of the techniques we use means that we can write a program to do all of the work for us, a scanner generator.

Quick Exercise 1

Let's lay the foundation for the rest of our session with this quickie:

Write a regular expression for the language consisting of all

strings of a's and b's that end in

abb.

Solution. This regular expression works:

(a*b*)*abb

So do many others. However, nested repetition makes expressions harder to understand and manipulate than we might like. This simpler regular expression also works and is closer to the natural language description of the language:

(a | b)*abb

Let's use this second expression as a running example for the rest of our session, as we learn a reliable and robust technique for turning a regular expression into a machine that recognizes the corresponding language.

Bonus exercise: Use the techniques we learn today to build an NFA and then a DFA from the first regular expression. Do you end up with the same DFA in the end? If so, why do you think that is? If not, how do the two DFAs compare?

Quick Exercise 2

Now, convert our regular expression into an FSA.

Solution. Given the repeated choice between

as and bs, an NFA seems like

the simpler alternative to me. Here is one candidate:

Is the process that you used to produce your FSA precise enough that we could write a program to do it for us?

[2a] Converting Any Regular Expression into a Nondeterministic FSA

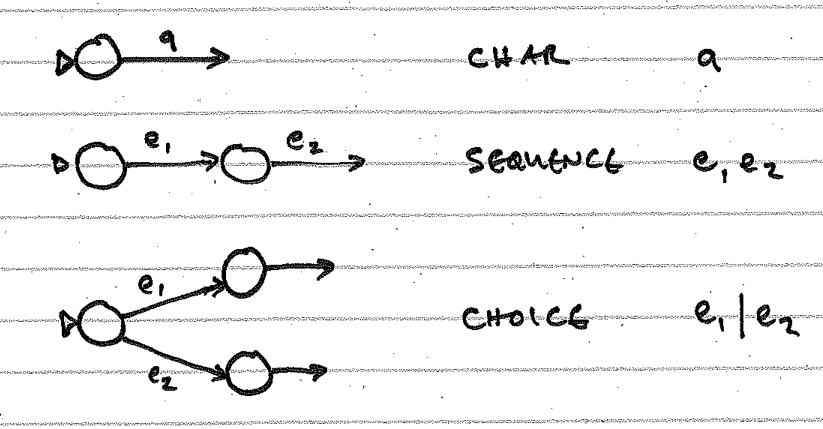

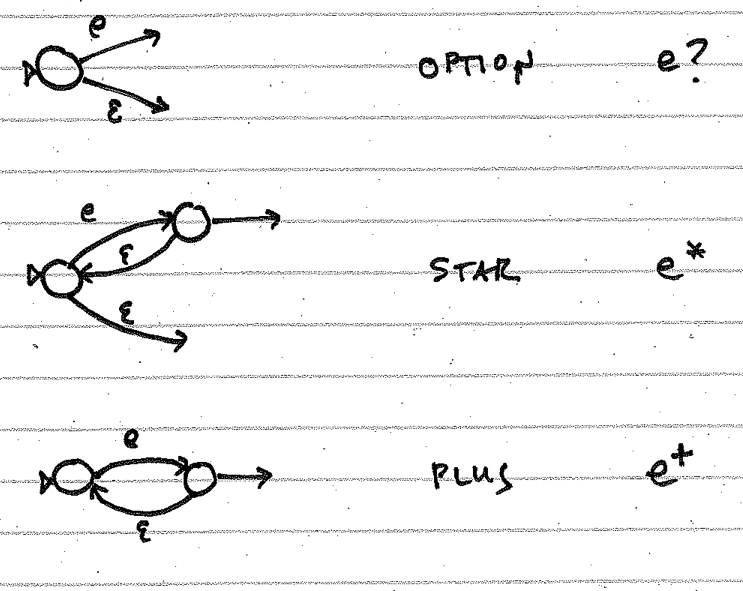

With some creativity and trial-and-error, we can create an NFA from any regular expression by doing the following:

- working through the elements in a sequence one at a time, and

- willingly using ε transitions to branch to and from paths in the regex whenever that is convenient.

There are some simple "moves" you can make as you work through the elements of a regular expression. Here are moves for the basic BNF elements that make up a regular expression:

And here are moves for BNF elements that involve choices and repetitions:

Some techniques follow the suggestion to use ε transitions

"willingly" with gusto, producing remarkably verbose automata.

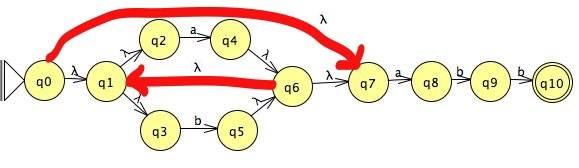

For example,

a textbook we once used in this course

describes an algorithm that produces the following NFA for

(a | b)*abb:

(The tool I used to create this graph uses λ in place of ε.)

The q0 → q7 transition handles the case of

(a | b)0, and the q1/q6

sub-machine with its q6 → q1 transition handles the

case of (a | b)+. Remarkable!

The disadvantage of such a technique seems obvious: it creates a lot of unnecessary nodes and ε transitions. The process is tedious for humans to implement, and the result is usually a FSA that requires a lot of guessing and backtracking.

The advantage is more subtle but very important. The process is mechanical and guaranteed correct. If you follow this process, you will produce a valid NFA for any regular expression. Furthermore, it is straightforward to automate some or all of this process in code. This means that a human programmer does not need to manage all of the details it requires.

Keep in mind, too, that we do not have to worry about the verbosity of such NFAs, because CS theory gives us techniques for "minimizing" an FSA. Those techniques are also straightforward to automate in code!

Creating an initial NFA from a small regular expression is usually a straightforward process, even when done ad hoc -- as long as you don't worry about creating the smallest or best automaton possible. We have techniques for improving the automaton later.

[2b] Converting a Nondeterministic FSA into a Deterministic FSA

From the standpoint of a programmer building a recognizer, an FSA is more useful than a regular expression because we can simulate it directly in code. That is, we can write code that acts just like the automaton. However, because it is nondeterministic, an NFA requires the ability to guess a path and backtrack when the guess is wrong. We would like for our recognizers to be deterministic. This will result in faster programs with a smaller run-time footprint.

Fortunately, as we noted earlier in this session, the set of languages recognized by NFAs is identical to the set of languages recognized by DFAs. We can use the elements of a proof for this claim to create an algorithm for converting any NFA into an equivalent DFA.

This is an example of one of the great connections between theory and practice. When a proof is "constructive", the construction in the proof can usually be translated into a program.

The idea is to simulate the NFA on all possible inputs, creating a new DFA as we go along.

- If the NFA has a state i with a single transition for the same symbol that goes to state j, we create a transition from state i to state j in our new DFA. However...

- When the NFA has a state i with multiple transitions for the same symbol that go to states j, k, ..., we create a compound state [j, k, ...] in the DFA.

- When we consider how to proceed from a compound state [j, k, ...] on a given symbol, we create a transition to the compound state [m, n, ...] that includes all the states that are reachable from any state in [j, k, ...].

We continue this process until we have covered all of the branches out of all of the states in the DFA we are growing. We need to be certain to handle all of the ε transitions, too, keeping in mind that they do not consume any symbols. In the end, any state in the DFA that contains one of the NFA's final states is itself a final state in the DFA.

This sounds dangerous. Won't we have to create an awful lot of states? Will the process even terminate?

Recall that "F" in NFA stands for "finite". An NFA consists of a finite number of states, say n. The process I described must terminate, because it can create at most 2n-1 superstates. That sounds pretty scary itself for large values of n, but in practice, the algorithm usually produces far fewer states, even for complex NFAs. This is especially true in the context of tokens for a programming language.

Let's try the process out on our simpler NFA above.

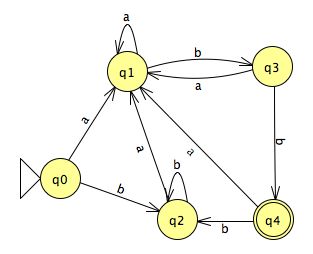

The result is this DFA:

Not bad at all. The 4-state NFA results in a 4-state DFA, without much more complexity. (Working with a small alphabet helps.)

What about the mechanically-produced 11-state NFA with all those ε transitions? The algorithm begins by producing this:

... because an a input can take us from q0 to either q4 or q8, via ε transitions, and a b input takes us only to q5. If we continue the process, we arrive at:

That's not too bad, either. The 11-state NFA results in a 5-state DFA, only slightly bigger and more complex than the simpler DFA produced from our simpler NFA. Again, working with a small alphabet helps keep the FSA small. Only those states in the NFA that have incoming a's and b's end up in the "superstates" of the resulting DFA.

Theory of computation can help us do even better. The translation technique described here is a bit more verbose than it needs to be. We can take advantage of "important states" when we compute the ε closure of a state, that is, the set of states reachable from the state on a given input. This approach creates a new state only in the cases when two sets of states have the same important states. The result can be smaller DFAs. (See Pages 134-135 of the Dragon book if you would like to learn more.)

Minimizing the Deterministic FSA

The verbosity of the techniques for converting regular expressions into NFAs and then into DFAs means that we usually have room to compress the resulting DFA into a more efficient machine. If we apply one of the optimization algorithms to the five-state DFA above, it produces:

... which is identical to the DFA we produced from our simpler NFA. We cannot do better, because it is the minimal DFA for this language!

One of the important conclusions we can draw from this experience is that we can use straightforward, mechanical techniques at each step along the way and produce a minimal DFA that recognizes our regular language. Another is that CS theory really can be valuable for us programmers.

We won't study minimization techniques in this course, in the interest of having time to learn other topics. If you are interested, you can read about them in your textbook or in the Dragon book.

Tools for Working with Regular Expressions and FSAs

Fortunately for us, these optimizing techniques are mechanical and thus programmable. Many people have done so.

I used JFLAP to generate my FSA diagrams for the last two sessions. It is a free tool created at RPI and Duke with support from the NSF. I also used JFLAP to do the convert NFAs to DFAs and to minimize the DFAs. You can download JFLAP from the project web site or from the course web site, which has a local copy of the version I use. It is a jar file and should run anywhere you have Java installed.

There are many other tools available out there. If you find a tool that you find to be useful, let me know. I will add it to the course resources page.

Writing Code to Implement Deterministic FSAs

Isn't writing code to implement a DFA just SMOP, a small matter of programming? While tedious, implementing a deterministic finite state automaton in code really is straightforward. For a large automaton, though, the code can become long.

Each state in a DFA becomes a state in the code. How can we implement states?

In a procedural style, we might implement each state as an

int to be switched on. For example:

int state = START_STATE;

switch (state)

{

case 0:

// consume character from input; change state var

break;

case 1:

// consume character from input; change state var

break;

...

}

The nested switch is simple enough to write, but it can become difficult to read, as it will likely spread over more than one page. We can often make such code easier to read if we implement each state as a function that knows which states to call on each possible character. For example:

protected void/Token state0( input )

{

switch (next character)

{

case a:

state1( rest_of_input )

break;

...

}

}

Finally, we can eliminate the need for nested code at all by implementing each state as a row in a data table to be processed. We can implement the table as a two-dimensional array, with states labeling the rows and input characters labeling the columns.

For example, here is a table for the

simple state machine

that recognizes (a | b)*abb:

a b

0 1 0

1 1 2

2 1 3

3 1 0

Now, we write code that starts in state 0 and uses the array to choose the next value for the state. In this table, state 3 is the only terminal state. If the automaton exhausts its input stream while in this state, it recognizes the string.

We can also use a dead state d as a destination if ever a character is not allowed out of a given state. If the automaton ever reaches this state, it fails to recognize the string. Dead states enable us to construct a complete table to drive the process.

In an object-oriented style, we can make each state an object. The result is a set of objects that know how to switch among themselves. When a state reads the next character, it can send the next state a message and tell it to process the rest of the input. This is similar to the state-as-function approach, only with the function decomposed into pieces that are wrapped in objects:

class State0 implements State

{

public String process( State[] states, String word, int pos )

{

if ( pos >= word.length() )

return "reject";

if ( word.charAt(pos) == 'a' )

return states[1].process( states, word, pos+1 );

// else( word.charAt(pos) == 'b' )

return states[0].process( states, word, pos+1 );

}

}

When a state recognizes a token, it creates the token and passes it back to the requestor.

For more on this technique, see the State design pattern.

I have created sample programs to demonstrate each of these techniques:

You will notice that, at least in Java, these implementations grow increasingly long and verbose. Yet real programmers sometimes use the longer approaches in practice. When do you think each of these approaches might be useful, and what do you think their advantages might be?

The sample programs are included in today's code zip file.

Why Implement an FSA At All?

Many programming languages provide regular expression tools as parts of the language now. Why not use those tools in our scanner, and skip writing code to implement the DFA at all?

Using a language's regex package to implement all or even most of a scanner is a recursive application of Jamie Zawinski's famous dictum:

Some people, when confronted with a problem, think I know, I'll use regular expressions. Now they have two problems.

(You can find the original quote from

alt.religion.emacs quoted

here;

a write-up of an archeological expedition to find the original

source of the quote is

here.)

We really do want to use regular expressions to model tokens. They are an invaluable tool when building a compiler. But using the regular expressions directly in our code, except in the smallest doses, makes code difficult to write, read, and modify. The regular expressions to model all of Klein's tokens would be a mess to work with.

Even more importantly, a hand-written scanner can be much faster than a regex-based solution. Russ Cox wrote the classic explanation of how to implement fast DFAs using Ken Thompson's technique about a decade ago, with several follow-up articles going deeper, and Eli Bendersky gives some empirical data from Javascript. The regular expression engines implemented by most programming languages does not use deterministic FSAs; they simulate the expression as an NFA and thus do a lot of backtracking.

The improvement in speed available by converting the regular expression to a DFA, especially a minimal one, is considerable. It also means that compilation time can be used for other tasks, such as static analysis and optimization, for which there are no theoretically optimal techniques to implement.

For your compiler project, I require that you implement your scanner using one or more DFAs. This will teach you a lot about how regular expression matchers work in your languages and produce a better compiler.

Project Check-in

Any questions?

Send me your team name and the name of your captain. If you have chosen an implementation language, please send me that, too.

Don't forget about the status check that is due on Friday.

As you begin to work on the project, I strongly encourage pair programming, even trio programming. Teams that pair a lot tend to learn faster. That learning will compound over the semester and keep everyone up to speed, making each team member more productive.