Session 22

Intermediate Representations

Opening Exercise

boolean.tm that takes three command-line

arguments, a, b, and

c. boolean.tm prints the value of

(a + b) < c.

Use 1 for true for 0 for false. For example:

> tm-cli-go boolean.tm 2 4 10 # (2 + 4) < 10? OUT instruction prints: 1 # YES HALT: 0,0,0 > tm-cli-go boolean.tm 2 14 10 # (2 + 14) < 10? OUT instruction prints: 0 # NO HALT: 0,0,0

Recall that, in TM, we can compare an integer only to 0, not to another integer.

Feel free to look back at any of the programs we built in Sessions 18, 19, or 20, if you think that will help.

Opening Solution

Here is my first attempt. A couple of things to note:

- I use R1-R3 to hold the arguments and compute into R4-R5.

-

Statement 4 computes the value of

(c - (a + b)), which is greater than zero if the condition is true. It uses that value to jump to the "true" code or fall through to the "false" code. - I allow myself two output statements and two exits from the program. Structured programmers everywhere cringe.

I wrote

a second version

of the program that eliminates the duplicate statements. It

resembles more closely the typical use of a boolean expression

in a Klein program: as the test on

an if-expression, with 'then' and 'else' clauses.

A couple of things to note:

- I use R6 to hold the value to be printed.

- There are now two jumps, one to the "else" clause and one over the "else" clause (after executing the "then" clause).

-

The

OUTandHALTstatements have been factored out and appear at the end program. Structured programmers cheer with joy.

Even this version can be shortened, if we use some things we know about TM and this code. Version 3 takes advantage of this knowledge:

-

We never use the original values of

aorcagain, so we can compute directly into their registers. This saves two registers. -

R6 has never been used before, so it holds a 0 already when

we start. We can eliminate one

LDCstatement. -

Because R6 already holds the value we want to print when the

test fails, we don't really have an "else" clause. The

"then" clause can fall through to the rest of the program.

We reverse the jump test to JLE and eliminate one

LDAstatement.

Can your code generator know these three facts, too, or other facts like them? It can — if it keeps track of certain information about the code it is generating. In a few sessions, we will see what information to track and how to use it!

As you begin to implement your code generator, you will want to think about how more complex Klein expressions affect the TM code it generates:

-

How would our TM program change if the left hand side of the

<expression were more complicated? - What parts of the program would stay the same?

- How would the program change if the right hand side were also a compound expression?

- What parts of the program would stay the same?

We can make the task of writing a code generator more manageable if we identify patterns such as these and use them to create templates for each kind of node in a Klein abstract syntax tree. More about that soon, too.

Where Are We?

We have been considering the synthesis phase of the compiler, which converts a semantically-valid abstract syntax tree into an equivalent program in the target language. Over the last few sessions, we have learned about the run-time system that is necessary to support every compiled program. This involves the allocating memory to data objects and generating the sequence of instructions needed to call and return from a procedure.

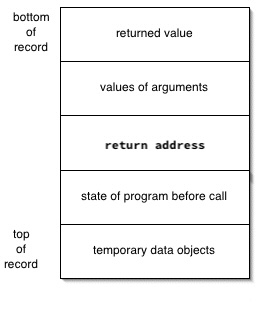

Last session, we reviewed several ideas for organizing stack frames. A simple form that may work for your code generator is:

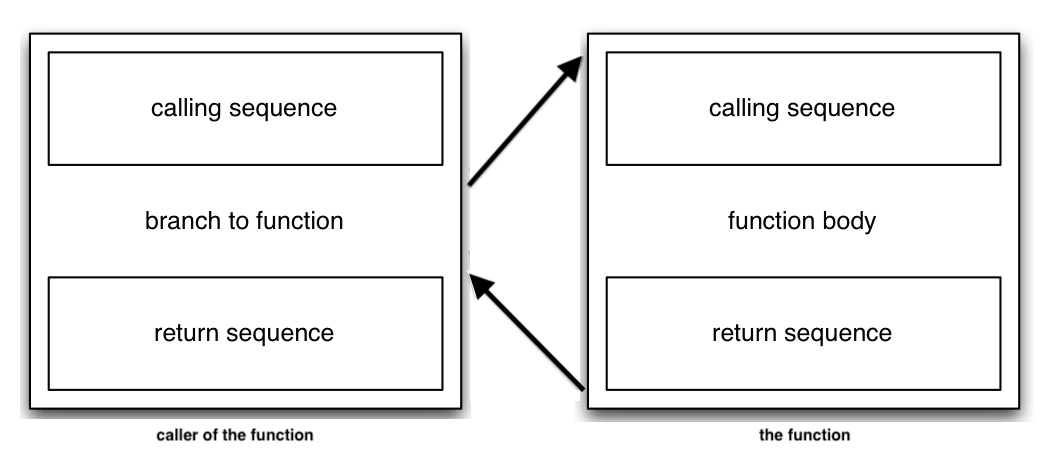

We also discussed in some detail the code that must be generated for function calls in order to set up and populate the stack frame. That resulted in the calling and return sequences distributed across the function call and the called function:

Our discussions over the last three sessions give us some hints about how to approach the code generator. Use those hints!

Now — finally! — we consider how to generate target code for a specific source program.

The Need for Intermediate Representations

Introduction

from CS 4550 students yet again.

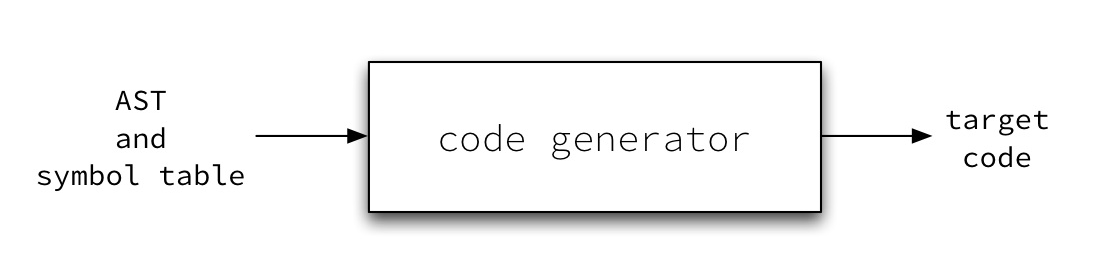

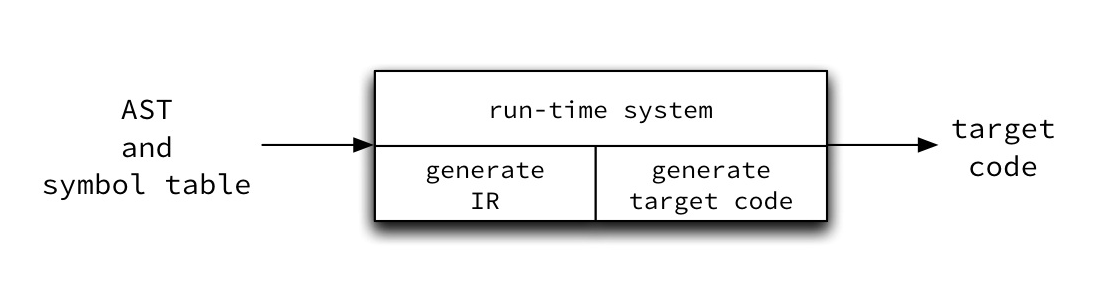

Well, not quite yet. Keep in mind where we are in the process of writing a compiler:

This one-block diagram hides a lot of complexity. Some of the target code that our compiler generates is common to nearly all programs. So we spent the last two weeks studying how to design a run-time system that works for all target code.

There are at least two good reasons for us not to jump directly to generating code for the target machine even now.

Machine-Dependent Target Code

A large part of generating code for a particular target machine is (surprise!) machine-dependent, but not all of the machine-dependent elements of code generation depend in the same way on the machine.

If we write a monolithic code generator, then any change in the target machine, even a small upgrade in the same processor, might cause changes throughout the program. If we write a modular code generator, with modules that reflect particular shearing layers in the generation process, then we may be able to contain changes in target machine specification to an easily identified subset of modules.

Distance from AST to Target Code

The abstract syntax tree for most high-level programs is still quite far from the level of assembly language. The task of translating it into any assembly language program, let alone an efficient one, is quite daunting. If we decompose the task into smaller steps, we will be able to generate code that is easier to understand, modify, and optimize.

Consider how simple

the opening exercise

was. Now imagine scaling that exercise up to, say,

farey.kln

(more about that program

below).

A modular code generator can take smaller steps and thus

be easier to write, test, and modify.

How Can We Proceed?

So, let's think of code generation in two parts:

- one or more machine-independent transformations from an abstract syntax tree to an intermediate representation of the program, followed by

- one or more machine-dependent transformations from the intermediate representation to machine code.

Following this approach, and knowing what we know about run-time systems, a more accurate block diagram of our compiler's code generator is:

What might an intermediate representation look like?

Intermediate Representation

As early as the mid-1950s, when the first high-level programming languages were being created, compiler writers recognized the need for an intermediate representation.

In 1958, Melvin Conway proposed UNCOL, "a universal computer-oriented language" that could bridge the gap between the "problem-oriented" languages being designed for human programmers and the machine language of a specific piece of hardware. The goals were the same as those outlined above: making it easier to write a compiler and port it to a new target machine.

You can see Conway's original paper — only three pages long! — in the ACM digital library, or read this local copy.

An intermediate representation enables us to:

- retarget the compiler to different machines more easily, and

- optimize code in machine-independent ways, without having to manipulate a complex target language.

An intermediate representation sometimes outlives the compiler for which it was created. Chris Clark described an example of this phenomenon in Build a Tree — Save a Parse :

Sometimes the intermediate language (IL) takes on a life of its own. Several systems that have multiple parsers, sophisticated optimizers, and multiple code generators have been developed and marketed commercially. Each of these systems has its own common virtual assembly language used by the various parsers and code generators. These intermediate languages all began connecting just one parser to one code generator.

P-code is an example IL that took on a life of its own. It was invented by Nicklaus Wirth as the IL for the ETH Pascal compiler. Many variants of that compiler arose [Ne179], including the UCSD Pascal compiler that was used at Stanford to define an optimizer [Cho83]. Chow's compiler evolved into the MIPS compiler suite, which was the basis for one of the DEC C compilers — acc. That compiler did not parse the same language nor use any code from the ETH compiler, but the IL survived.

The language of the Java virtual machine is a more recent example of an IR created for a specific programming language that may well outlive that language. A good language design usually pays off, sometimes in unexpected ways.

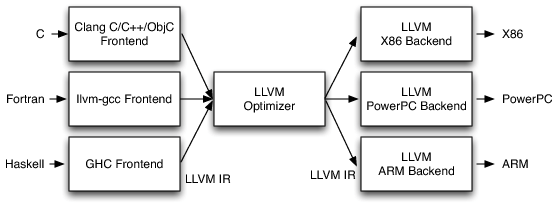

LLVM's intermediate representation is a language-agnostic IR that has, in recent years, become a standard in the world of compiler construction.

LLVM is quite influential these days, in large part because of its IR, which is the heart of the project. It won't surprise me at all if its IR outlives all the parsers, optimizers, and code generators in its suite of tools.

If you would like to understand the value of an IR better, or see the role an IR plays in LLVM, check out IR Is Better Than Assembly, a very nice tutorial.

Choosing an Intermediate Representation

The primary input to the code generator is an abstract syntax tree.

Candidate IR: The Abstract Syntax Tree

Strictly speaking, the AST itself is an intermediate representation along the path between the source program and the target program. However, the tree is a two-dimensional structure that is quite far removed from the linear nature of the target language. One of our first goals is convert the AST into a linear format. From there, the jump to the target language will be easier.

What might an IR look like? And what might it do for us?

Let's use the AST for the expression

a := b*(-c) + b*(-c)

as an example to consider some alternatives.

Candidate IR: Postfix Notation

One common intermediate language is based on the idea of a stack machine. A stack machine is an interpreter of postfix expressions. Some hardware provides machine-level support for such operations, so generating a postfix representation of an AST can be an efficient way to create the target program. In other cases, a virtual machine interprets a postfix-like program. That is how the Java virtual machine works.

Some higher-level languages use a stack machine as their model for source programs. Forth is a language used for control programs embedded in medical devices that attracts the attention of curious programmers in every generation. Manfred von Thun designed Joy, a purely functional language, using function composition rather than function application as its fundamental operation. +

A few years ago, I spent some time helping a Forth compiler writer port his compiler to Mac OS X. I also once spent much of a sabbatical once playing with Joy, including writing a a Scheme interpreter for a large subset of the language. It's a fun way to program! I sometimes introduce Joy in my programming languages course as perhaps the next big thing in programming languages.

We can convert the AST above into a postfix expression by doing a post-order traversal of the tree:

a b c - * b c - * + :=

In this linear form, we might want to use the Joy-like

dup primitive (short for duplicate) to

optimize the program's IR:

a b c - * dup + :=

Any pre-, in-, or postfix traversal converts a tree into a linear form. Note that the postfix expression does not represent the edges of the tree directly. They are implicit in the order of items on the stack and the number of arguments expected by the operators on the stack.

Candidate IR: Records

Another common approach to IR is based on records or

structs.

In the simplest form, each node is represented as a record that contains pointers to the records of its children, and the program becomes an array of records. Terminal nodes use all of their slots to record information about the item. Non-terminals use one or more of their slots to hold the integer indices of their children. For example, we might represent our AST above as follows:

As we move down the array of records, we move up the tree from leaves to root, using record numbers to refer to nodes lower in the tree.

This representation points us toward a third approach, three-address code, that provides most of the advantages we seek.

Three-Address Code

We can do better than an array of records by choosing an IR that moves us closer to the level of the machine, without tying us to the details of any particular machine.

Consider three-address code. Statements in a three-address code have a form based on this pattern

x := y op z

The name "three-address code" follows from the fact that each

expression uses at most three objects or locations. In this

form of the pattern, op is a primitive operation.

The three addresses are x, y, and

z.

-

yandzare the operands toop. -

xis the location where the result is stored.

Because all expressions in three-address code contain exactly one operator chosen from a small set of low-level operators, we must decompose compound expressions into sequences of simpler expressions. This generally requires that we use temporary variables to hold the intermediate results.

For example, we might convert this expression:

x + y * z

into the following three-address code program:

t1 := y * z t2 := x + t1

To do so, we create the temporary names

t1 and t2

for locations to hold intermediate results.

We can convert our example AST above into the following three-address code program:

t1 := - c t2 := b * t1 t3 := - c t4 := b * t3 t5 := t2 + t4 a := t5

An optimizer might recognize the same duplication we saw in our postfix IR and create this simpler three-address code program:

t1 := - c t2 := b * t1 t3 := t2 + t2 a := t3

Notice that we have already adapted the general form of three-address code in two ways.

- First, some operators take only one argument, so they need only two addresses.

- Second, some assignments merely copy a known value to another location. Such expressions need neither a third address nor an operator.

Note that the assignment is implicit in all three-address statements.

You will also notice that I used a temporary name for the value

of the entire right hand expression, even though I immediately

copy the value into the user-defined variable a.

The optimizer or code generator may well eliminate this extra

step later, but the use of the extra temporary variable makes

it easier to design a simple algorithm for generating

three-address code statements.

At least two features of three-address code make it a good representation for optimization and code generation. First, it forces the compiler to unravel compound expressions and flow-of-control operations into sequences of simpler expressions. Second, expressions can be rearranged more easily, because the program uses names for intermediate values.

A three-address code program represents the nodes and edges that appear in an AST, but gives temporary names to internal nodes. This linearizes an AST just as a postfix expression does, but the three-address code program represents the edges explicitly via the temporary variables.

Generating Three-Address Code in the Compiler

Three-address code is a convenient intermediate representation for many compilers, including your Klein compiler. What do we need to do next in order to use it? We will:

- design a simple three-address code language that includes the features we need for working with Klein and TM

- look at how we can represent 3AC in our compiler

- look at how we can generate 3AC for the different kinds of nodes in our abstract syntax tree

That's where we will pick up next time!

A Reference Program for Farey Numbers

Earlier, I used

farey.kln

as an example of a complex Klein program. Farey numbers are

a way to use rational numbers to approximate floating-point

numbers to an arbitrary precision. For example, the best

approximation for 0.127 with a denominator ≤ 74 is 8/63.

I can compute this result by evaluating

farey(127, 1000, 74).

How can I be sure that my Klein program works before I have access to a working Klein compiler? I can't, but I can do something to increase my confidence: I can write a reference program in another language.

When I first wrote the program that became

farey.kln, I wrote two reference programs.

My first version

is written in standard Python, using the standard algorithm.

Then I created

a second version

by slowly refactoring the first one until it was written

in a Klein-like subset of Python, using only expressions and

statements available in Klein. It runs and gives the same

answers as the standard Python program, and so is a perfect

starting point for writing a correct Klein program.

Yes, I love to program. Please write me a Klein compiler.