Session 20

Organizing Run-Time Storage

Opening Exercise

Last time, we opened with an exercise that caused us to think about what happens when a Klein integer gets too big (≥ 231) or too small (< -231). We decided that, given the nature of our source language and target platform, Klein will exhibit the "wraparound" behavior of silent over- and underflow:

MAXINT() + 1 → MININT() MININT() - 1 → MAXINT()

This makes Klein like Java and many other languages with fixed-size integers. It is also consistent with the behavior of TM.

That exercise brings to mind another question: What are the largest and smallest integers that we can represent in TM? My abbreviated TM language spec doesn't say.

It doesn't even say that the only data type in TM is the integer, which is important to know!

How might we determine the value of MAXINT in TM? What kind of TM program could we write to find it?

Your task:

If you would like a jump start, I have all the statements you need, but they are out of order. Rearrange them to reconstruct the program we need.

Running a Solution

Here's a TM program that prints out the largest positive integer on the machine. Let's run it to see the answer. Let's also time to the execution to see how long it takes...

$ time tm-cli-go solution-v1.tm OUT instruction prints: 2147483647 HALT: 0,0,0 Number of instructions executed = 1 real 0m56.544s user 0m55.944s sys 0m0.593s

That's on a 2023-era MacBook Pro.

My solution increments two integers on every pass through the loop, which executes 2147483648 times. Knowing that TM integers wraparound like Klein integers, we can write a more efficient TM program that increments only one integer on every pass, cutting the loop body time in half. How much faster is it?

$ time tm-cli-go solution-v2.tm OUT instruction prints: 2147483647 HALT: 0,0,0 Number of instructions executed = 1 real 0m46.151s user 0m45.629s sys 0m0.514s

It cuts total runtime by about 20%.

How much of that runtime is due to TM's virtual machine? Check out this C program to find out! (Spoiler: C is fast.)

Where Are We?

Last time, we turned our attention to program synthesis, the phase of the compiler in which we convert a semantically-valid abstract representation of a source program into an equivalent program in the target language.

Our first concern is the run-time system, the code that is necessary in order to execute any compiled program, including any predefined routines. This code will include the mechanisms we need to allocate and address data and to call and return from functions.

The functionality we began to grow two sessions ago and looked at in detail last time underlies two essential elements of a running program:

- how the names of data objects in a program are allocated storage locations in memory and then addressed at run-time

- how computational processes are activated through function calls

A key point to draw from last session is the distinction between static notions that reside in program text and dynamic notions that exist as the program executes.

Klein's simplicity means that we don't have to deal with the full range of possibilities. For example, Klein does not have global data objects, assignment statements, or higher-order functions. But implementing even a simple run-time system teaches us a lot about how languages work at the machine level.

Organizing Run-Time Storage

Introduction

The storage associated with a running program consists of three kinds of object:

- the generated target code

- data objects created by the program

- a control stack, to manage procedure activations

Space for the target code is allocated statically, that is, once, at compile time. The control stack is allocated dynamically, as the program runs. The data objects may be allocated statically or dynamically, depending on the nature of the object and the nature of the language.

At the time it produces its output, the compiler knows the size only of the statically-allocated objects: the generated target code and the static data objects.

How much it can know about the control stack and about objects allocated dynamically — indeed, whether it can know anything at all about these — depends on the nature of language it is compiling.

Data Objects

In general, we would like to maximize the number of objects whose memory needs are known at compile time, because these objects can be assigned to fixed locations in the run-time memory of the target program. The compiler can compute addresses for these objects and write them directly into the target code. This makes the target code both simpler and faster to execute at run time.

The size of some data objects, though, can be determined only at run time. Perhaps the size of a record is not determined until the user running the program specifies the size of a string it contains. Perhaps an array's size depends on the number of records in an external data file. These objects must be created dynamically under program control.

The run-time system must provide a separate source of storage locations for objects such as these. Typically, this source is called the heap.

This use of

the term "heap"

differs from its use as the name of the data structure known

as a "heap". A compiler's heap can be implemented using a

heap data structure, but it doesn't have to be!

If you haven't learned about the heap data structure yet,

you really should. Check out

this web page

or

the Wikipedia page.

The heap is one of the cooler data structures around.

Some languages do not allow programmers to create data dynamically, but many modern languages do. We will consider the organization of static objects in more detail beginning later in this session, and the organization of dynamic memory briefly next time.

Control Stack

What about the control stack? For most languages, the size of the control stack cannot be known at compile time because, in general, the compiler cannot know the sequence of procedure calls that will be generated when the program is executed. This means that the storage allocated to the stack must be able to grow and shrink dynamically at run-time.

When some part of the program calls a procedure, the running program must interrupt its execution path and store information about that path, such as the value of the program counter and the machine registers. This information is stored in an activation record or a stack frame.

Note: Our code in yesterday's exercise used registers for most of its work, but obviously that won't scale up unless the target machine has a lot of registers!

When a procedure returns, the program restores the program counter and registers so that the interrupted execution path can be resumed. The activation record for a procedure generally also includes data objects created by the procedure.

We call this structure a control 'stack', but we use the term more loosely than the stack data structure typically allows. For example:

- Many languages require that an executing program have access to entries in the stack other than the topmost entry. For example, a procedure or code block may refer to a variable defined in a wider scope.

- Some languages even require a heap data structure for the control stack, because the lifetime of procedure activations does not fit a tree model. For example, think about a language that permits closures that refer to free variables, such as Racket.

We will consider the organization of the control stack in more detail beginning later in this session.

Memory Layout

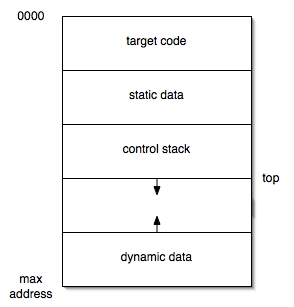

In order to account for the configuration of target code, data objects, and control stack, a typical compiler might organize its run-time memory in this way:

In this image, the control stack grows 'downward', toward higher addresses, and the dynamic memory storage growing upward. The address of frames lower in the stack can be computed as negative offsets from the top of the stack. This is a standard technique used by compilers because, on many machines, such computations can be done efficiently by storing the value of top in a register.

From this image, we can see one good reason to allocate as many data objects as possible statically. In order to run worst-case programs, the compiler must accommodate large dynamic memory and control stack partitions. To do so, the run-time system will take up much more space than the average program needs.

Some practical notes for your Klein compiler:

-

TM has separate memories for instructions and data. The

target code segment in the above memory is stored in

IMEM, and the rest is stored inDMEM. Your code generator won't have to account for a target code region in DMEM. -

In most compilers, we could swap the directions of the heap

and the control stack. Klein does not support data objects

allocated dynamically, so we don't need a heap at all. By

having the the control stack grow downward toward the

maximum address, we can compare the value in

DMEM[0]to the top of the stack when testing to determine whether we have enough space available for a new stack frame. - You may want to reserve a register to hold the value of top, too. In class, I will typically use R6 for this purpose.

Organizing Activation Records on the Control Stack

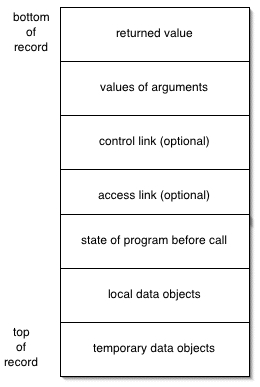

A common way to lay out an individual stack frame is:

Modern compilers often deviate from this layout by using registers to pass data values into and out of a procedure. This is attractive because registers are faster and do not require extra space. It is a viable alternative because many modern computers provide enough registers that the compiler has enough at its disposal to use a few for this purpose.

The state of the program before the procedure call consists of any data that the calling procedure will need when it resumes activation, and which the called procedure will overwrite. The most common data stored here is the contents of all the registers.

Historically, the optional control link points to the activation record of the calling procedure, and the optional access link points to the location of non-local references. Not all languages require these, for a variety of reasons:

- The compiler may know the location of one of the items in question.

- They may occur at a fixed location.

- Their addresses may be computable from other available information.

- The language may not allow non-local references.

The control link pointing to the calling procedure's activation record is sometimes called the status pointer. In TM, we need this value to be in a register. That means the status pointer will be stored with the other registers in that section of the stack frame. (We will talk about the status pointer in more detail next time.)

Klein does not have non-local references, so we don't need to store an access link. In lieu of an access link, our Klein compiler can store the return address in the stack frame.

The local data objects region holds objects that are bound explicitly to names within the procedure. The temporary data objects region holds objects that are created implicitly in the course of evaluating expressions.

Klein does not support local variable declarations, but it usually needs a region for temporary data objects. For example, some Klein functions require many temporary objects. Consider the expression:

square(a+b) + c - gcd(d, e)

How many temporary objects might the compiler create in the course of implementing this expression? I see at least four and perhaps as many as ten.

The order of the items in the activation record is intentional. The values needed only by the called procedure, such as local and temporary data objects, appear on the top of the stack. Values needed at the time of the procedure's call and return (the arguments and return value, respectively) appear at the base of the record, where they are easily accessed by both the called function and the caller.

The size of each region can be computed at run time, when the procedure is called, or at compile time. Whenever possible, the compiler should do these computations, because that allows more efficient allocation of space. Some objects require run-time computation, such as an array whose size is determined at run time.

Organizing Local Data Within the Stack Frame

The amount of storage required for each data object is determined by its type. For the basic integer, floating-point, and character types, the compiler knows the fixed number of bytes to allocate on the target machine. An aggregate data type contains other objects, so its size can be computed only if the number and size of its parts is known at compile time. Many aggregate data types require run-time computation of size.

Even in such cases, the compiler must organize memory for data objects in the activation record for a specific procedure at compile time. It keeps track of the number of memory locations allocated at any point in time. In this way, it can compute a relative address for each local object with respect to the beginning of the local data region, or the beginning of frame itself. These offsets can be used to refer to each data object in the generated code.

The details of data object storage have historically been driven by the addressing constraints on the target machine. For example, the integer addition instruction on some machines requires that its arguments be aligned in memory, perhaps at locations with addresses that are divisible by 4. This may require that memory be padded with unused bytes or packed into a more compact form.

The choice between padding and packing raises a familiar trade-off. At run-time, padding consumes extra space. Packing consumes extra time, because data items must be unpacked before they can be used. Packing also requires code in the run-time system to do the unpacking, which takes space!

TM does not require that memory be aligned in any way; its DMEM is simply an array of integers. A Klein compiler, though, could save space by packing multiple boolean values, each of which requires only one bit, into a single integer value. A program with many booleans could benefit greatly in terms of stack space from this practice, but at the cost of run-time unpacking. (This would be a really neat experiment for a Klein compiler...)

One way to isolate these decisions from the rest of the compiler is to encapsulate as many of the details of the target machine as possible from the machinery that generates code. To do this, we can create abstractions within our compiler, such as a stack frame abstraction, to help manage these decisions at compile time.

Allocating Static Data Objects

Sometimes a name can be associated with a single storage location at compile time. When this is possible, the compiler does not need to generate any run-time support for the object.

Remember: bindings do not change at run time — only values do!

In order to do this, the compiler must know the size of the object as well as any constraints on its position. This eliminates any dynamically-sized aggregates. The compiler must also be able to use a single binding for the name. This eliminates the data objects local to a recursive procedure, because those objects may require multiple bindings for a given name.

So: the compiler will be able to allocate data objects statically for non-recursive procedures and for fixed-sized global objects.

How does the compiler allocate static storage? As described above, the compiler must:

- commit to a location for the object in the static data region,

- compute an offset for this location from the top of the region, and

- use this address for all references to the data object in the target code.

The symbol table can be used to store the target address of a statically-allocated data object. The code generator can then look up the address whenever it needs it.

Note: the compiler may be able to do the same for several components of the stack frame, namely, the information stored about program state at the time of a procedure call.

Allocating Stack Frames Statically

As we saw briefly in Session 19, we may be able to allocate memory for activation records at compile time. If a language does not allow recursion, or allows only tail recursion, then a program will never need more than one activation record for any procedure at a time. So, the compiler can treat activation records like other static data objects and allocate a single activation record for each procedure.

In such cases, there is also no need for a separate control stack. Instead, an implicit stack forms as procedures call one another and store links pointing back to the procedures that called them. This makes for an incredibly efficient run-time system! The venerable language Fortran allows this kind of memory layout, and it is one of the sources of Fortran's efficiency in data-intensive scientific computation

(This also reminds me of how we simulated linked lists in Fortran, which has only static memory...)

Generally, though, we must allocate memory for activation records dynamically, at run time.

An Aside: An Implication of Reference Semantics

After learning how a compiler organizes run-time memory for a program, you may appreciate more how Java's reference semantics for objects simplifies the Java compiler. Even though objects can be of arbitrary size and thus need to be allocated from dynamic memory, every Java object variable is a fixed-length reference to such an object. This means that (1) the values bound to Java names can be allocated statically and (2) objects to be placed on the control stack (as local or temporary objects) have a size known at compile time.

Where is the cost of this approach? At run-time, the system must pay a small price in dereferencing each object as it is used. This cost is not significant when considered in the context of looking up methods to be executed.

On Modules 2 and 3

Some thoughts on Projects 2 and 3, including their grades:

- I ran only a few negative tests for each assignment. If your parser failed one or more of these tests, then you probably want to test deeper. Even if your parser passed all these tests, they don't provide much evidence that your parser is correct. You probably want to test more!

- Your parse table is probably pretty long. The parsing algorithm is pretty short. Putting them both into the same file obscures the algorithm — and makes it harder to use the parser with a different table! Ideally, put the parse table in a separate file or module and then import it into your parser. If not, you can improve readability by putting the algorithm at the top of the file and the parse table at the bottom.

-

Naming files matters. Your test cases, demo Klein programs,

and other code will be easier to understand and use if they

have descriptive names and, if appropriate, organized into

separate directories. For example:

-

module3-tests/ -

module3-test1.kln -

log.kln

-

- Be sure to include at the top of your README a section that lists any specific files for the assignment, especially new Klein programs you write, and any specific instructions for me.

Keep in mind how grading for the project works. The grades you receive for Modules 1 through 6 are only initial marks toward how your final score is computed. You can get full credit for those components at the end of the semester, with the effective grade for each component being the average of the initial grade and the end-of-project grade.

You may fix, improve, and extend every part of the compiler throughout the semester. Just be sure to give the current module, whatever that is, your primary attention. (That is a general rule; there may be exceptions. Module 4 is one of them.)