Session 19

A Program's Run-Time Environment

Opening Exercise

function MAXINT(): integer 2147483647 function MININT(): integer -2147483647 - 1 function main() : integer MAXINT() + 1

What happens when we run it?

What do you think should happen?

Handling Integer Overflows in Klein

I think we have found a hole in the Klein language spec. It doesn't say what happens when an arithmetic expression produces a value larger than the largest integer, or smaller than the smallest. There are at least four options:

-

overflow or underflow, silently

Programmers sometimes refer to this as "wraparound":MAXINT() + 1 = MININT() MININT() - 1 = MAXINT()

Java specifies this result in its language spec, which says "The integer operators do not indicate overflow or underflow in any way." -

overflow or underflow, loudly

Languages such as Rust, Zig, and Ada throw an error when an integer overflows its specified type. This is also what TM does on divide-by-zero. -

change type

Python and Racket silently switch from regular integers to long integers when a value exceeds what its regular number type can hold.>>> sys.maxsize 9223372036854775807 >>> sys.maxsize + 1 9223372036854775808 # umm... maxsize?

-

undefined behavior

The C language spec does not say what happens in this case, so the behavior can be implemented in whatever way the compiler writer chooses. This is handy for compiler writers ... but a little scary for compiler users. I guess we can try always to avoid the error.

You can make a case for any of these approaches, though these days most computer scientists and programmers find undefined behavior to be unacceptable. With the speed of modern processors and the low cost of memory these days, most real languages can offer "real" numbers without much of a penalty to users in most circumstances.

We should define the behavior we want in Klein. Given the nature of our target platform, let's adopt the wraparound behavior of silent over- and underflow:

MAXINT() + 1 → MININT() MININT() - 1 → MAXINT()

You may use these constant functions in your programs. They are defined in lib.kln. They can be handy in many numeric programs, and that way Klein programmers like me don't have to memorize them!

Side note: Eight years ago this month, researchers from the Technical University of Munich published a paper called Practical Integer Overflow Prevention in which they describe a way to (1) use static analysis and a little theory to detect integer overflow errors and then (2) generate "code repairs" that prevent the overflows from happening at run-time. I'm curious to see how easily this technique generalizes to other applications.

Yes, I love to program. Your Klein parsers are awfully handy now as I prepare for class. Make me a full Klein compiler, please!

Follow-Up Exercise from Last Time

Last session, we dove into TM assembly language programming, in preparation for our move into code generation for our Klein compilers. At the end of the session, we completed the fourth exercise and looked at a TM solution.

That leaves one exercise that we have not considered, Exercise 5, and its solution. Instead of treating it as a code-writing exercise, let's use it as a code review exercise. Our goal is to begin to understand how a program calls functions and returns from them.

05-two.tm and answer these questions

about the code:

-

The comments on Statements 6 and 8 say that they

store a value.

Why do they use anADDinstruction instead of anSTinstruction? - Functions are called twice in this code. Which code is common to the two callers?

- Functions return twice in this code. Which code is common to the two returners?

-

Statements 9 and 13 use

DMEM[2]as a storage location for a return address.- Why did these statements have to move a value?

-

Could they have used a register to hold that value

instead of a slot in

DMEM? If so, which one?

Make a list of any questions you have about the code, too.

This code demonstrates a very simple run-time system. It

defines the machinery that calls the body of the main program

and prints its value. You can use this code as a starting

point for kleinc's run-time system. Of course,

your code generator will generate the run-time system!

When a function is called, the caller must do some work. The called function has something to do, too. When a function returns, the returning function must do some work. The caller has something to do, too.

We refer to these as the calling sequence and the return sequence, respectively. They are an important part of your project's code generator.

Next week, we will consider the calling and return sequences in detail. This week, we prepare for that discussion by exploring a program's run-time system and the organization of run-time storage, including the records on the control stack

Segue to Program Synthesis

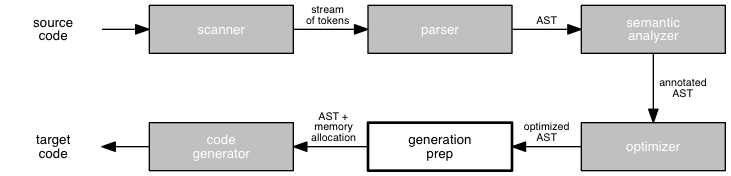

To date, we have been concerned with the analysis phase of the compiler: those stages that build a relatively abstract picture of the source program being compiled. This phase includes lexical analysis; syntax analysis, which creates an abstract representation of the program; and semantic analysis.

We now turn our attention to the synthesis phase of the compiler: those stages that convert our semantically-valid abstract representation of a source program into an equivalent program in the target language. (We'll save optimization, which is an optional stage of the compiler, to later in the course.)

Before we dive headlong into the process of generating target code, let's first consider the foundation on which synthesis will be done. Over the next few sessions, we will study the run-time system that is associated with a compiled program. This system consists of the program-independent code that enables the compiled program to execute in the fashion defined by the language, including the basic framework of the generated program and any routines that are loaded at run-time along with the generated target code.

The Role of the Run-Time System

To date, our concern has also been solely with static features of the source program, those features which can be understood and verified by examining only the text of the source program. At run time, though, this program will execute on the target machine, and static features of the program will take on their dynamic meaning.

For example, the same name may mean different values at different times during the execution of the program. In one case, it may be used as a temporary variable name. In another, it may appear as the formal parameter on a simple function definition. In yet another, it may appear as a formal parameter for a recursive function.

The run-time system makes it possible for a generated program to behave in the way defined in the language specification. It produces the dynamic meaning expressed in the static form of the code.

The idea of a run-time system is quite general. Languages such as Java and Python rely on a virtual machine to execute their target languages. The virtual machine embodies these languages' run-time systems, so compilers for these languages do not need to generate this code when processing a specific program. A virtual machine can be an especially powerful and portable form of run-time system, which accounts in part for the popularity — and success — of the approach.

Our focus in this course is on the sort of run-time system associated with a language that runs natively on some "real" machine. Our compiler will generate code for the run-time system each time it processes a source program.

Our study of run-time systems includes the two main elements of a program's execution profile:

- the allocation of memory for objects referenced in the program, and

- the activation of computational processing through function calls.

These two elements correspond to the two sides of any program: data and behavior.

Today, we begin to explore these two elements. Some of this material will be familiar to you already. Our goal is to build a strong base of knowledge for implementing a code generator.

A Quick Exercise

- May a function call itself, even if only indirectly?

- May a function refer to a name defined outside its definition?

- May a function be returned as the value of a function call?

Answering these questions will help you begin to think about the issues involved in building a run-time system.

Run-Time Systems and Source Language

Both memory allocation and procedure activation are determined in large part by the semantics of the source language.

Memory Allocation

How we allocate space for the data in a program depends on the type of the object. We may be able to represent basic types directly by mapping them onto equivalent types in the target machine. Characters, integers, and real numbers are examples of types where this commonly works.

For other basic types, and for most or all of the constructed types in our source language, we will have to do several things:

- construct a representation in terms of types available on the target machine,

- allocate instances of this representation, and

- manage these values within the run-time environment.

Procedure Activation

The declaration of a procedure associates a name with a statement, the body of the procedure. This is a static binding. Execution of the same procedure creates an activation that runs the code of the procedure body in the context of the program's current state. This is a dynamic relationship.

Generally, there is one copy of the code defined in the static binding of the name to its body, but there may be many copies of the code being run, each with its own copies of the data it is using. A program activation allocates memory for the objects required by the procedure in order to execute.

This is a recurring distinction in the implementation a compiler, in the study of programming languages more generally, and in computer science even more generally. You should be becoming quite familiar with this Big Idea by now.

Consider

this example of a quicksort program.

+

Lines 3-7 declare the procedure

readarray. When the name appears on Line 23,

we say that that the program calls the procedure.

This program appears in the classic compiler text, the Dragon book.

In some languages, a procedure call can occur either as a

stand-alone statement or as part of a larger expression.

In Line 16, a call to the procedure partition

is used in an assignment statement.

The declaration of the partition procedure in

Lines 8-11 also declares two special identifiers, the

integers y and z. We call these

the formal parameters of the procedure. They are

like local variables but are special in that any code that

calls partition must provide the initial values

for them. The values that are passed are called the actual

parameters of the procedure, or the arguments.

Line 16 provides the integers m and

n as actual parameters in a call to

partition.

Different calls to a procedure can provide different actual

parameters. In Lines 17, 18, and 24, the

quicksort procedure is called with three

different sets of arguments.

The Pascal run-time system must support the creation and use of these data objects for any legal Pascal program. This is complicated by the order in which functions are called and used.

Control Flow Among Procedures

On a sequential machine, program control flows sequentially, with one step following another. But each procedure call branches to a new sequence and returns to the point of the call, which in effect creates and extends multiple paths. As a result, it is often useful for us to think of control flow among procedures as a tree of activations.

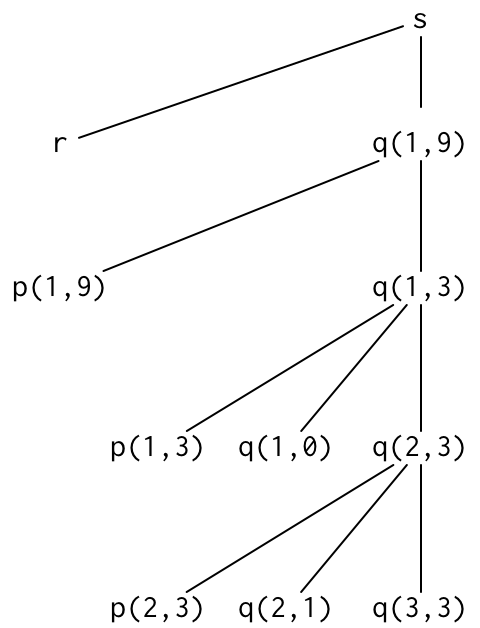

For example, consider this partial tree corresponding to the execution of the quicksort program:

Note: At run-time, there will another subtree

branching to q(5,9) from q(1,9).

Every time a procedure is called, its formal parameters are

initialized with the values of the actual parameters and the

statements in its body are executed. In the tree above, the

partition procedure is called three times: by the

first execution of quicksort and then by the two

recursive executions of quicksort from within

quicksort's body.

We call each of these executions an activation. The lifetime of an activation is the time spent executing the body of the procedure, including any procedure calls it makes. This sequence of steps is determined at run time.

Each time a called procedure finishes execution, it returns to the same point in the calling activation. This means that the lifetimes of any two procedure activations are either disjoint or nested. It also means that we can use a stack to manage the flow of control among procedures.

In this sense, recursive procedures are not really special. It's just that, on a recursive call, the nested activation is of the same program text as the calling activation. This leads us to an answer to the second question in the quick exercise above: Without recursion, we could simplify the allocation of memory by creating a single activation record for each function and then using it for all the calls to a function!

With recursion, though, we need distinct activation records

for each call to a function. Otherwise, the run-time system

will not be able to nest activations of the same procedure.

Re-consider the partial activation tree for a run of the

quicksort program shown above. At two points in the

execution, the program requires four distinct activations of

quicksort.

The run-time system does not contain all of the information in this tree at any time. To determine the flow of control at run-time, we can walk the tree in a depth-first manner. The state of the control stack during execution corresponds to paths in the tree as they are seen during the walk.

Variable Declarations

Let's return now to how memory is organized at run-time.

The declaration of a variable associates a name with some information. This is a static feature of the program. At run-time, the name will be associated with a piece of memory and the information used to govern its use. Such information can include type, scope, and modifiability.

In some languages, declarations are explicit, as in Pascal:

var i, j, x, v : integer; /* Line 9 in our example */

or in Java:

int i, j, x, v;

Other languages allow or even require implicit declarations, in which the programmer simply uses a name and the run-time system infers whatever information it can about the memory.

For example, in Ruby, this statement:

@foo = n

implicitly declares an instance variable named

@foo. The @ indicates the scope

of the variable, which is all the information the run-time

system needs to know. Ruby variables are dynamically typed,

so there is no need to infer type information.

In Fortran, this statement:

MAX = 50

implicitly declares an integer variable named MAX.

Any variable name that begins with a character in the range

[I..N] is assumed to denote an integer, unless the program

includes a prior declaration to the contrary. Fortran is a

much simpler language than Ruby, so there is no need to infer

scope information.

The scope of a declaration of a name is the part of program in which the declaration applies. When we refer to the program as a static entity, scope refers the portion of the text in which the name is visible and is sometimes called the region of the variable. When we refer to the program as a dynamic entity, in terms of its execution, scope means also the lifetime of the variable, the time during which the object exists in memory.

Many languages allow the same name to be used for different objects in a program. When there are multiple declarations with the same name, the language's scope rules are used to determine which object a particular reference refers to. This leads to a distinction between local objects, declared in the immediate scope, and non-local objects, declared in a scope that contains the immediate scope.

For example, our quicksort program reuses several names. It

declares the variable i three times, on Lines

4, 9, and 13. It also refers to variable a

locally once, on Line 6, and non-locally twice: on Line 22

and presumably, somewhere in the code elided as Line 10.

Some languages use naming conventions to assist the programmer and compiler in identifying the scope of an identifier. For example, the first character of a Ruby identifier provides scope information:

$— a global variable@— an instance variable-

[a-z]or_— a local variable

(A first character of [A-Z] indicates a

constant, which is neither type nor scope information, but

modifiability information.)

A symbol table, created either as part of semantic analysis or as preparation to generate code, is a tool that enables the compiler find the declaration that corresponds to a particular reference at compile time. In some languages, the symbol table can be built on the fly, as the compiler processes nested scopes. +

You may recall the stack of variable declarations constructed by the lexical addresser in your Programming Languages course.

Variable Bindings

At run-time, each name in a program will be bound to a particular data object during its lifetime. Such a binding connects the name to a storage location in memory, which holds a value. The same declaration of a name may be bound to different data objects at different times during execution, such as when a function is called multiple times.

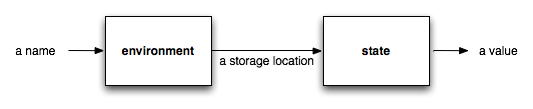

An environment is a function mapping names to storage locations. These locations can hold different values at different times during execution. The function mapping storage locations to values is called the state of the program.

Note that an assignment statement changes the state of

a program but not the environment. Line 22 in our quicksort

program changes the value of a[0] but

not the location at which it is stored. In functional

programming, we think of a name as referring directly to a

value, with little or no thought to the storage location

between them. This works fine, because we don't use assignment

statements to change the state of the program.

Creating a new binding changes the environment of the

program. Line 24 of the program calls the

quicksort procedure, which adds bindings for

m, n, and i to the

environment. The function call also changes the state of the

the program by assigning initial values 1 and 9, respectively,

to the two formal parameters.

What value does the state function hold for i

immediately after the call?

Static Versus Dynamic

We have now seen three variations of the interplay between static and dynamic features of a program. In each case, a static feature of a program's text corresponds to a dynamic feature of the program's execution:

| static feature | corresponding dynamic feature |

|---|---|

| the definition of a procedure | the activation of a procedure |

| the declaration of a variable | the binding of the name |

| the scope of a declaration | the lifetime of the name's binding |

The correspondence of a dynamic counterpart to each static feature of a program is one of the Big Ideas of computer science. Be on the look-out for it everywhere. Knowing about the correspondence of static to dynamic features, and understanding the distinction between them, will help you be a better programmer and computer scientist.

Understanding the distinction between static among dynamic features is essential to writing a compiler. Our target machine distinguishes between the memory that holds code and the memory that holds data, which will help us distinguish between the definition and activation of a function. The other two relationships will be managed within our compiler at compile time and implemented directly into the target instructions it produces.

If this sounds a little fuzzy, don't be concerned. Our next few sessions will make these distinctions clearer.