Session 21

The Calling and Return Sequences

Bonus "In The News": A Compiler Vulnerability

Is Klein vulnerable to this compiler-driven security flaw ?

Recap: Run-Time Systems

The Recap

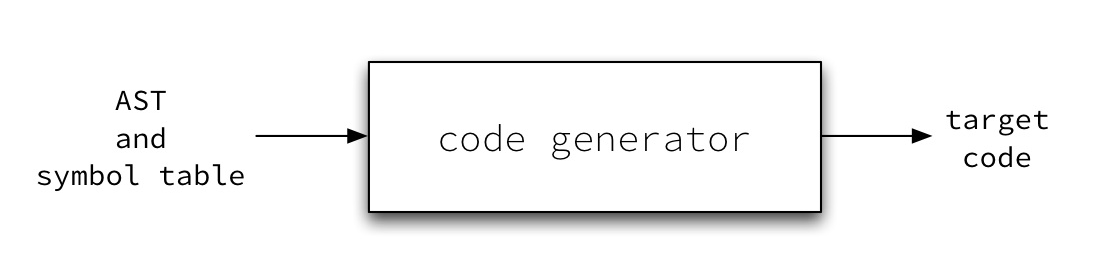

Where are we? We are now studying the final stage of a compiler, the code generator:

But consider the simplest Klein program, a contraction of print-one.kln :

function main(): integer

1

Even a Klein program with no if expressions, no

compound arithmetic or boolean expressions, no excess function

definitions, and no function calls requires machinery to

execute the main program and print its value. This code is

common to all programs.

So we have spent the last few sessions studying how to design the run-time system required for all target code. The run-time includes routines that are loaded at run-time in addition to the target code generated for a specific source program. It enables the target code to execute in the fashion defined by the language.

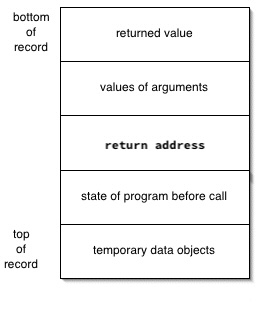

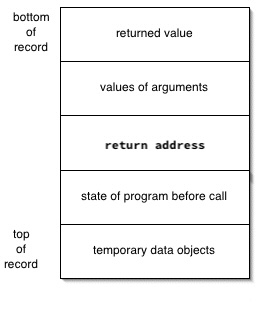

Last time, we learned a bit about how to organize the run-time storage for a program as it executes, including how to organize the activation records that appear on the control stack and how to allocate storage for static data objects. For Klein programs, we can distill the typical stack frame down to something even simpler:

Now that we know how to organize activation records, we can consider how to allocate them. That is our main topic for today: the calling and return sequences that animate the execution of functions called at run-time. The processes by which one piece of code calls a function and by which that function returns control to the caller is one of the great divisions of labor in programming.

We will conclude our discussion of the run-time system by taking a quick look at an issue that arises when compiling any language: how to make symbol tables more efficient. You implemented a symbol table as part of your semantic analyzer, and you'll be extending and using it for the rest of the project.

This Week's Reading

The course homepage page links to a handout as reading for this week. This book chapter (5MB pdf) describes the theory and practice of implementing a run-time environments. I think you will find Section 7.3 (stack-based environments) and Section 7.6 (a simple implementation in C) to be relevant and perhaps useful in creating a run-time system for Klein.

Implementing a Run-Time System: Project 5

Module 5

asks you to implement the simplest code generator possible for

Klein: a program that takes the AST of print-one

and produces a run-time system around a single integer value.

Design Hints

Some hints specific to the project:

Design DMEM and the stack frame.

What is the simplest thing that will work? Slots for the return value, a single argument, and a return address. What if you put the return value in a designated register?

Design IMEM.

We saw a program that is quite similar to the goal output of Project 5 when we first studied TM a few sessions back: the solution to Exercise 5. This TM program consists of a prologue that calls the main function, a main function that calls a square function, and a square function.

The run-time system is of fixed size.

+

Then put print(), which is of fixed size.

Finally, put main(). The jumps are predictable.

That will change when we expand the code generator to handle programs with command-line arguments.

Programming Hints

Some hints about the programming process:

- Think about the sections of code generator one at a time.

-

When something comes up that you need to handle, think

about it immediately or defer it to a specific time.

Example: setting the top pointer (r6?) in the prologue. -

When something comes up that you will need later,

make a note.

Example: how to choose a register to work with, especially inprint() - When in doubt, decompose the problem into smaller steps. Make a helper function, have it return a constant value for now, and fill in more complex details later.

- You have all the programming tools you've learned at your disposal. Use what you know!

Demystifying the Code Generator

Your code generator will be a program that produces lines of TM code as its output. That's just text. Don't make it any bigger in your mind than it is.

Any program that produces a TM program is a code generator. Let's look at three.

- Some of the lines can be hardcoded — example 1.

- Others depend on variables, such as a value or an operation — example 2 (value), example 3 (value and op code).

- Later, still others depend on other kinds of variables, such as the number of arguments. Sometimes, this will generate code that is longer.

Our discussion today of the calling and return sequences

should help you get started. They tell us what code our

prologue needs in order to call main() —

and what code main() needs in order to call

print() — and what those functions need to

do in order to return. That's the code your project must

produce!

Thinking Ahead

Your Project 6 code generator will produce code for arbitrary expressions and arbitrary function calls. By then, you'll understand much better what to do there. For now, stay focused on the simple AST your code generator will receive!

The Calling and Return Sequences

Recall the layout of a typical Klein stack frame, shown at the right.

As we noted last time, modern compilers often deviate from the typical stack frame layout we saw last time, for a variety of reasons. Some source languages do not require the optional links. Many modern target architectures offer so many registers that a compiler can use them to pass data values into and out of many procedures. This approach simplifies the stack frame that the run-time system must construct and use.

Even so, there is considerable complexity in creating and using stack frames. How does a compiler implement a procedure call?

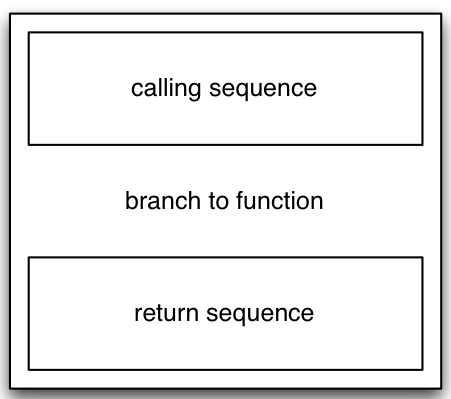

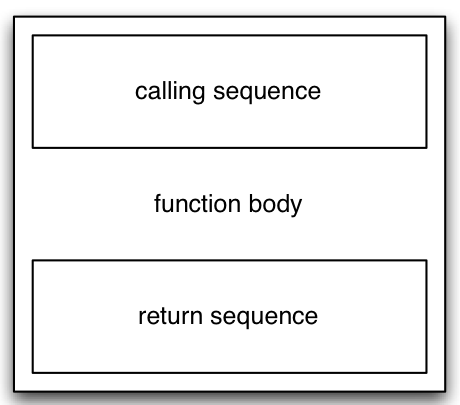

Each procedure call requires a sequence of instructions to allocate an activation record and then store some initial information there. This is called the calling sequence.

When the procedure is finished executing, the compiler invokes a complementary return sequence to restore the state of the machine so that the calling procedure can complete its execution.

The instructions in both the calling sequence and the return sequences are usually shared between the calling procedure and the called procedure. Requirements imposed by the target language and perhaps by the operating system determine much of the split between the two.

Quick Exercise. In general, we would like for the called procedure to do as much of the work as possible. Why?

Consider the case in which a procedure is called from n

different places, say a utility function such as Klein's

MOD() function or a method in a commonly-used data

structure. Any instructions for the calling sequence that are

executed by the callers will be generated n times, once

for each caller. The instructions that are part of the called

procedure will be generated only once!

The caller usually computes the values of arguments passed to the called procedure, because each call has its own specific values. These are typically stored at the bottom of the activation record, so that the caller can access them without having to know the layout of the rest of record.

Temporary data objects pose something of a problem. While their size and number can be known at compile time, they may not be fixed at the time the record is allocated. Later phases of the compiler, especially the optimizer, may change their number or size as a part of their tasks. So they typically come at the top of the frame, where they do not affect the caller or the offsets computed for the rest of the record's fields.

This is another motivation for implementing a stack frame abstraction in the code generator. The stack frame class or generator can take care of details not available to other parts of the code generator.

The Calling Sequence

Here is a typical calling sequence. Assume that there

is a register named status pointing to the

beginning of the region labeled

state of program before call in the typical stack

frame shown above. The caller can initialize all the fields

below this pointer, using addresses computed as negative

offsets from it, while the called procedure can initialize and

access the fields above the pointer using positive offsets.

The calling procedure

- creates the new activation record

- evaluates the arguments to pass to the called procedure and stores them in the designated locations of the activation record

- stores the return address in the control link field

-

stores the current value of

statusin the access link field -

sets the value of

statusto the appropriate position in the new activation record, past the calling procedure's local and temporary data and the called procedure's parameter and link fields - adjusts the value of

top

The called procedure

- saves the values of the program counter and registers

- initializes its local data objects, perhaps allocating them first

- begins execution

The Return Sequence

The corresponding return sequence might look like this.

The called procedure

- stores its return value, if any, in the designated location of the activation record

-

restores the program counter, the machine registers from

the stack frame, and the value of

status -

adjusts

top, effectively deallocating the activation record

The calling procedure

- copies the return value from the old activation record into the appropriate data object, whether local or temporary

- resumes execution

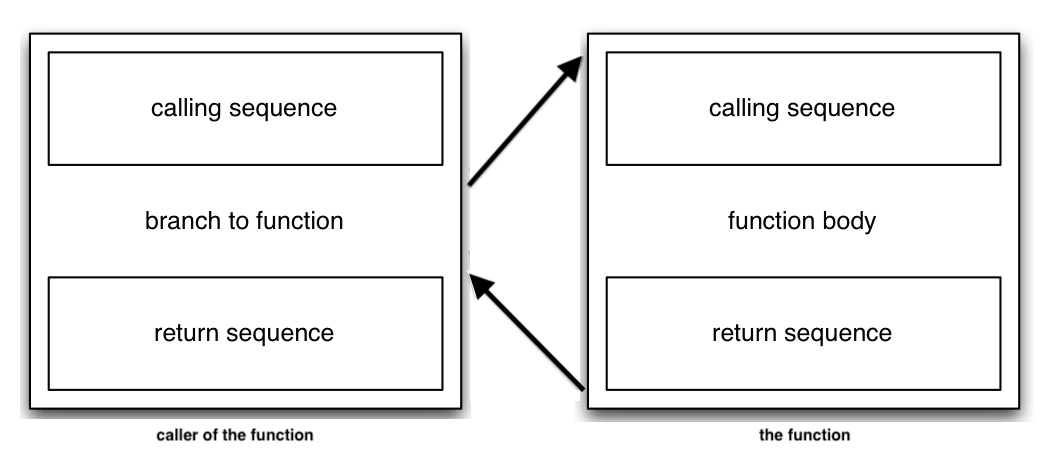

Putting the Sequences Together

When we take into account the calling and return sequences, the target code for a function call in the calling procedure looks something like this:

... and the target code for the function itself looks something like this:

Consider this example:

i := sos(2, a);

...

int sos(int x, int y)

{

return x*x + y*y;

}

A round trip for the function call looks something like this:

This technique works whenever a stack is suitable for recording the activations of procedures. However, if either of these conditions is true:

- the value of a local name outlives the procedure activation

- the called activation outlives the calling activation

then we cannot use a stack to implement the flow of control, because control cannot be modeled as a last-in, first-out process. The compiler must use another way to organize storage, such as a heap. (Think about how Racket might work when it returns a closure.)

Implementing Symbol Tables

The symbol table is an important part of the run-time system, as it tells the compiler what object a particular name refers to. As we've seen, this affects when and how new objects are allocated. Though we can generate a symbol table as early as the lexical analysis phase, the run-time system places particular demands on the table.

For example +, the definition of a stack frame may depend on knowing the nesting depth of a reference. Such changes mean that the symbol table must either be updated during semantic analysis or built at a later stage.

See the optional readings available for today.

Because the symbol table may contain many objects and may be referred to by the compiler many, many times, compiler writers would like for symbol tables to be as efficient as possible at storing and retrieving items. Much work on efficient data structures and algorithms for symbol tables has been motivated by compiler construction, including:

- The representation of identifiers: How can an identifier of an arbitrary length be represented unambiguously in a fixed-sized field?

- The implementation of hash tables: The goal is to create a function that distributes a set of strings uniformly over a structure that uses the smallest amount of space possible. Because the items to be stored in the table are always structures keyed by identifiers, we can pursue problem-specific solutions, ones that take advantage of identifier representation (if only as strings) and the fact that identifiers in programs share some common features. Knowing as much as we do about the domain, we can often construct nearly perfect hashing algorithms!

This topic is too big for us to consider it any deeper in one semester. For your compiler, choose a suitably efficient data structure and implementation in your source language.

Optional Readings

I leave three other issues as optional readings:

- how to pass parameters, which relates directly back to our discussion of the activation record

- how to access names that are not declared locally,

- how to allocate and deallocate dynamic data objects

These are important parts of compiler construction, but they are not especially relevant for compiling Klein. If you've ever wandered what we mean by "garbage collection", though, you might want to read the section on dynamic data objects.