Session 17

Type Expressions and Type Checking

Where Are We?

We are now past the middle of the term on the calendar, and we have crossed over into the second half of the compiler project as well. After Project 3, your team has a parser that accepts syntactically legal Klein programs and produces abstract syntax trees for them. However, we know that your parser does not accept only legal programs, because the parser could not enforce requirements outside of the context-free grammar.

In Session 15 and Session 16, we began our discussion of semantic analysis, the phase of the compiler that determines whether a program "makes sense" according to the meanings of the language's constructs. It checks for elements of syntactic correctness that are beyond the capability of the parser and checks for elements of semantic correctness defined outside the grammar. Like syntactic analysis, semantic analysis also performs a pragmatic second task: annotating the AST with information that will assist in code generation.

Our primary focus for semantic analysis in this course is on type correctness, a semantic check that ensures variables, expressions, function calls, and statements behave in the ways specified by their types and the operations on them. That is our primary topic for the day.

Today, we look in more detail at the kind of type checking that

a Klein compiler must do, in particular if

expressions and functions. Then we will take a brief look back

at the semantic checker for Fizzbuzz, to see what type checking

looks like in code. This will finish our discussion of semantic

analysis.

First, though, let's spend a few minutes thinking about the other parts of semantic analysis. That might be helpful, as your Klein semantic checker has to do more than type checking!

Quick Notes

Next session, we move onto the synthesis of target code in the TM assembly language. A short reading and lab exercise will prepare you to use the TM virtual machine. Be sure to work through the assignment before our next class!

The slides for this session are available as a PDF file, if you'd like to see a brief version of the algorithms you will want to implement in your semantic checker.

Language Requirements Outside the Grammar

Part of verifying a program's semantic correctness is to show that the program satisfies all of the non-grammatical requirements of the language. Your assignment for Module 4 identifies at least five such requirements that can be found in the Klein language spec.

Three of the five deal with function names at the global level. We can implement each of these checks with a loop over the list of program definitions that make up the program. For example:

for f in list of function defs

if f.name = "print"

then addError("user-defined function named 'print'")

A similar loop can check to see if there is a function named 'main'. A third loop can check to see if all function names are unique.

All three of these checks can be done with a single loop, if we do a little bookkeeping:

f_named_main = false

list_of_names = []

for f in list of function defs

if f.name = "print"

then addError("user-defined function named 'print'")

if f.name = "main"

then f_named_main = true

if f.name in list_of_names

then addError("duplicate function named", f.name)

else add f.name to list_of_names

if !f_named_main

then addError("no user-defined function named 'main'")

This approach walks the list of function definitions only once.

The other two requirements work at the level of individual functions. They, too, can be checked in a single pass over the list of function definitions, by examining each function's parameter list and then walking its body to find variable references.

This kind of semantic analysis does not require any new ideas from the course, just a little programming.

The Basic Idea of Type Checking

Now for type checking. The basic idea here is relatively simple, too.

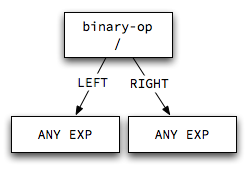

Consider a typical node for, say, a Klein division expression:

According to

the language grammar,

the left and right operands to the / operator can

be any expression. They might be an integer literal, an

identifier that holds an integer, a call to a function that

returns an integer, or another arithmetic expression. They

could also be boolean values or expressions that evaluate to

booleans. If both operands are integers, then this node is

legal. If either operand is not an integer, then this node is

invalid.

To type-check this or any other node, a semantic checker needs to...

- Type-check its parts.

- Apply a type rule to the results.

The type rule for the divide operator, or all binary arithmetic operators, is something like this:

if type(left operand) == integer and type(right operand) == integer then type of node = integer else type of node = error

This process performs a post-order walk of the abstract syntax tree using structural recursion.

Type Checking if Expressions

In the usual case, assigning a type expression to an

if is pretty straightforward. Consider:

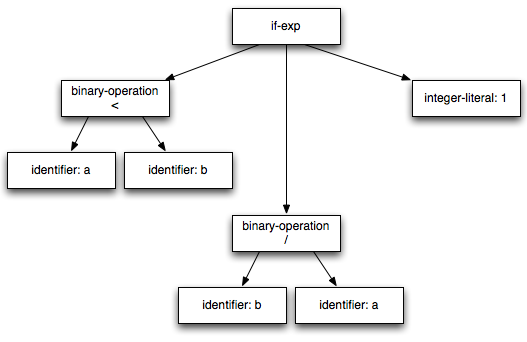

if (a < b) then b / a else 1

The AST for this expression looks something like this:

To type-check a compound expression, we have to type-check the

expression's parts and use those results to type-check the

expression. An if expression's test must be a

boolean; if it isn't, then there is a semantic error. The

"then" and "else" clauses ordinarily must return the same type.

In this case, that type is integer.

The type rule might be written as:

if type(condition) == boolean and type(then) == type(else) then type(if-exp) = type(then) else type(if-exp) = error

A Familiar Question

I alluded to this last time, so now let's take it on...

if (a < b) then b / a else false

What if we change a < b to true?

I can think of at least two possibilities. Ask yourself: Is there any context in which a Klein programmer could reasonably use this expression?

This Type or That: A Union Type

Applying the type rule for if expressions given

above, the type of:

if (a < b) then b / a else false

is in error. We can't use it as a value in a typed program.

If it is the body of a function, then it has to produce a value of a specific type. If it is part of a larger arithmetic or boolean expression, then its value will be used by an operator or function call that expects a value of a specific type. So, in general, the then and else clauses have the same type.

This line of reasoning led one team in a previous semester to ask the question (a very short optional reading) that inspired the exercise. It's a great question, because it helps us determine how to implement a Klein semantic checker and helps us understand type checking at a deeper level.

Is there a way that we can use that if

expression in a valid Klein program? There is one context in

which it is valid: the value is passed as an argument to the

print function:

print(

if (a < b)

then b / a

else false

)

The language spec says that print() returns no

value, but it doesn't say anything about the type of the value

passed to it. print is omnivorous! Er, that

should say polymorphic. It can take this

if expression as an argument and print a value of

either type.

Can we support this behavior in our Klein type checker? We can, if we create a new kind of type expression:

OR(type1, type2)

An OR type says that a value will be of either

type1 or type2. The OR type may

be valid in some contexts, such as passing the value to a

polymorphic print function, and invalid in others

— just like any other type. Consider:

1 + if (a < b)

then b / a

else false

The type checker will determine its validity when it checks

the expression that contains the if expression.

The Klein language specification is fairly typical. It does

not define the type system as an entity in its own right, only

implicitly as a result of combining and using expressions.

print's looseness creates a potential problem

— or a potential opportunity.

For us, it is an opportunity. You get to create a structured type expression in your Klein compiler.

Types Have Structure

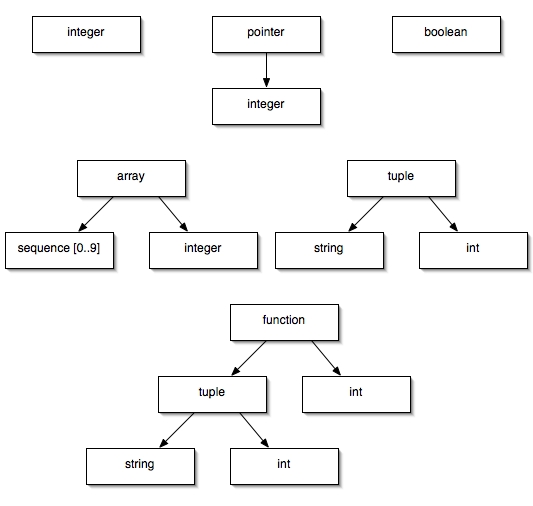

Last session, we encountered the idea that

types have structure.

That's because, in addition to the base types of atomic data

values, there are types associated with constructed types,

such as a pointer to an int or an array of

booleans. A semantic checker thus works with

type expressions,

which can be defined inductively as follows:

- A basic type is a type expression.

- A type created by applying a type constructor to one or more types is a type expression.

As we saw last time, though, the universe of type expressions is bigger than this. In addition to type constructors, some languages enable programmers to create type names or to use type variables when specifying types.

Trees are a useful representation for type expressions. Here are a few:

Type Checking Functions

The one structured type expression required by the Klein language spec is the function type. This type plays a role in checking recording the types associated with function definitions and function calls. Because functions can take different numbers of arguments, we can define the function type more simply if we define a tuple type, too.

The type rule we need to type-check a function definition looks like this:

if type of body == type of return type then type of function def = function(parameters type, return type) else type of function def = error

Assigning a type to a function call requires comparing the type of the arguments to the type expected by the function:

if type of function def = function(s, t) and type of argument list = s then type of function call = t else type of function call = error

Even with this simple and incomplete idea of functions, we can explore many of the interesting issues involved in type-checking functions.

- To allow functions of more than one argument, we generalize the s on the left hand side of the function type to be a tuple. You need this for Klein.

-

To allow higher-order functions, we allow one or both of:

- one of the types in the tuple to be a function type

- the type on the right hand side of the function type to be a function

mapprocedure as(s→t, list(s)) → list(t)

Algol, a statically-typed language, had this feature — way back in 1960! C has this feature in a more roundabout fashion, through its use of function pointers.

Klein does not allow higher-order functions. (Can you find evidence for this in the language spec?)

Type expressions such as these mean that determining whether two types are equal to one another is more complex than comparing to unitary values. We have to compare the parts of a constructed type expression by recursively comparing their structures.

A Look at a Type Checker in Action

Even a simple language can benefit from this sort of semantic analysis. Let's consider the semantic checker in the Fizzbuzz compiler we first saw in Week 1. It doesn't propagate types up through a tree of expressions, but it will give you a sense of how straightforward the code to check a program's semantics can be.

Note a few things:

- This type checker does not annotate the AST nodes. It needs only to ensure that each node meets the semantic requirements of the language.

- Each node is a compound expression that is checked based on the values of its parts. The value returned for the list of assignments is the conjunction of the values of each individual assignment.

- The type checker does build a symbol table, for use by the code generator. The checker itself uses the symbol table to check on the uniqueness of the program's words.

Quick exercise: Add a check to determine whether the same number is used in two different assignments. We should probably at least warn the programmer about such a case.

Wrap-Up

Can you believe that there is still a whole lot more to learn just about type checking, let alone semantic analysis more generally? There is. However, let's move on. We have a lot to learn about run-time systems and code generation!

Required Reading for Next Session

To prepare for our transition to code generation, work through this introduction to the TM simulator before Session 18.

If you do not have Linux or Unix running on your own

computer, you can do this work on the

student.cs.uni.edu server.

If you have any questions or need any help, please let me know.

Optional Readings

If you would like to read about type checking in more detail, check out this bonus reading on type checking a small language. The language in this reading has more features than Klein, so you get to see what type rules for other kinds of statement and expression might look like. The reading defines a complete type system for the language — and even has an exercise for you to do for practice!