Session 16

Semantic Analysis

Opening Exercise

Here is a Klein function used in two "excellent number" programs [ 1 | 2 ], which occasionally comes in handy:

function length(n: integer): integer

if (n < 10)

then 1

else 1 + length(n / 10)

It is syntactically and semantically correct. The parser tells us that it is syntactically correct, but last time we saw four different ways that a function like this can be wrong:

- gives the wrong type of value to a primitive operator

- passes the wrong type of argument to a function

- refers to a variable that doesn't exist

- returns a value of the wrong type

If you can't think of four, consider issues that can arise when there are multiple formal parameters or when a file contains multiple functions.

Each of things on your list points to a test case: we can change one token or one grammatical unit of the program and have a new program that is semantically incorrect but still passes the parser.

Semantic Features to Check

Including the four kinds of error we saw last time, here are a few errors that we could find in a function definition like this one:

- a function returns the wrong type of value

- an expression uses a variable that doesn't exist

- an expression gives the wrong type of value to an operator

- a function call passes the wrong types of arguments

- a function call passes the wrong number of arguments

-

the condition on an

ifexpression is not a boolean -

the then and else clauses of an

ifexpression have different types (?)

(We will consider the last item again later.)

If we step up to functions with multiple parameters and programs with multiple functions, we also have:

- two or more formal parameters on the same function have the same name

- an expression calls a function that does not exist

- two or more functions have the same name

-

there is not function named

main -

there is a function named

print

If we loosen our definition of "wrong", there can be even more:

- presence of a variable that is never used

- presence of a function that is never used

- presence of an unnecessary function

- presence of a code path that can never execute

- presence of code that never terminates

(That last one can be hard to recognize...)

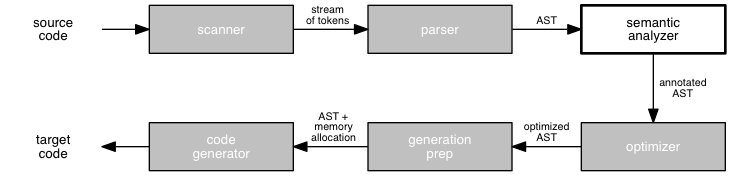

Where Are We?

The parser can guarantee a syntactically correct program, but it cannot guarantee a semantically correct one. You may recall at least two reasons for this from our discussion of syntactic analysis. First, programs are context-sensitive objects, but we use a context-free grammar to model the language. Second, we occasionally leave even some context-free properties out of the grammar in order to simplify the parsing process.

So: we must check the abstract syntax tree produced by the parser to verify that it is semantically correct. We refer to this step as semantic analysis. The same sort of analysis can also add other kinds of value by helping the programmer to make the program better.

Last time, we briefly considered the task of semantic analysis. We saw that this stage of the compiler has two primary goals:

- to ensure semantic correctness, and

- to prepare the abstract syntax tree for code generation.

and can provide a third service:

- to inform the programmer of things that are legal but perhaps unintended.

We then took a quick look at some of the issues involved in semantic analysis to ensure correctness.

Today, we will consider briefly the other kinds of semantic analysis that a compiler can do and return our attention to ensuring correctness, specifically checking type correctness.

As we discuss semantic analysis, you may want occasionally to

ask yourself,

How many of these features does Klein have?

The answer will give you an idea of what your semantic analyzer

for Klein will need to be able to do.

Beyond Program Correctness

Semantic analysis can achieve more than simply ensuring that a program in semantically correct.

Semantic Analysis to Help the Code Generator

The second goal of semantic analysis is pragmatic: to prepare the abstract syntax tree for code generation. To satisfy this goal, the semantic analysis phase usually produces two kinds of output:

- It adds information to the AST that makes it easier to optimize the program and generate target code. A common annotation to the AST is the addition of type information about identifiers and expressions to the corresponding nodes in the tree.

- It produces other artifacts that can support the rest of the compiler. One such artifact is a symbol table that records information about the identifiers used throughout the program.

This analysis is not necessary in order ensure that the program satisfies the language specification, but it can make later stages of the compiler more effective.

For example:

- If the semantic analyzer can determine that a value will be an integer rather than a floating-point, then the code generator can select more efficient assembly language instructions.

- If the semantic analyzer can determine that a value is constant rather than variable, then the code generator can store the value in a register and reuse it.

Semantic Analysis to Help Programmers

In addition to these two primary goals, semantic analysis can help programmers in other ways. Consider this Klein function:

function MOD(m: integer, n: integer): integer m - m*(m/m)

This program passes the parser and a type checker, but is it

semantically correct? Perhaps the programmer intended to use

the n but made a mistake. Perhaps the

programmer would like to delete the argument's second

function. Or perhaps this is exactly what the programmer

intended! In any case, a semantic analyzer can recognize

anomalous code and let the programmer know about it.

Semantic analysis can check features that are desirable but not strictly necessary to a program's correct execution. For example, it might:

- identify "dead code", which can never be reached

- identify variables that are never used

-

point out more idiomatic usage, such as the use of

i++instead ofi=i+1

The last of these gives rise to an entire class of tools: static analyzers that check style, portability, and idiom. The first and best known program of this sort is Lint, which was created at Bell Labs in the 1970s to flag "suspicious" C code and report potential portability problems. Lately, I have been applying the Python linter pycodestyle to most of new Python programs in an effort to learn standard Python style (and to break my mind out of stylistic blinders).

Tools such as Lint and pycodestyle can be built for any language, even Klein. They can identify bad style and other kinds of non-standard code. This sort of semantic analysis can be built right into a compiler, but it is often built in to editors and IDEs or done by stand-alone tools.

A Moment in History

Speaking of Lint: October 8 was the anniversary of

Dennis Ritchie's death.

Ritchie created the C programming language and wrote the

first C compiler. As we have discussed a few times, C is the

foundation for much of the work in the world of compilers, if

only because most compilers are initially written in, or

compile to, C. In addition, C and Unix (which Ritchie

co-created with his lab partner, Ken Thompson) set the stage

for open systems and portable software. Lint was written by

one of Ritchie's colleagues at Bell Labs.

We can take this idea one step further. One of the common uses of semantic analyzers in contemporary programming environments is in tools that support automated refactoring. Even the simplest refactorings — say, renaming a variable or a method — require semantic analysis to ensure that the new name does not create a conflict with an existing name in the same scope. A semantic analyzer can check for conflicts that human programmers might miss, especially in large code bases.

Implementing Semantic Analysis

In this course, we focus our semantic efforts on verifying type information and building the symbol table. These can be done using straightforward structural recursion over the abstract syntax, either pre- or post-order traversal.

Many other static checks can be implemented using the same technique and can even done at the same time as checking types or building the symbol table. For example, the compiler can verify uniqueness of names at the time each entry is made in the symbol table.

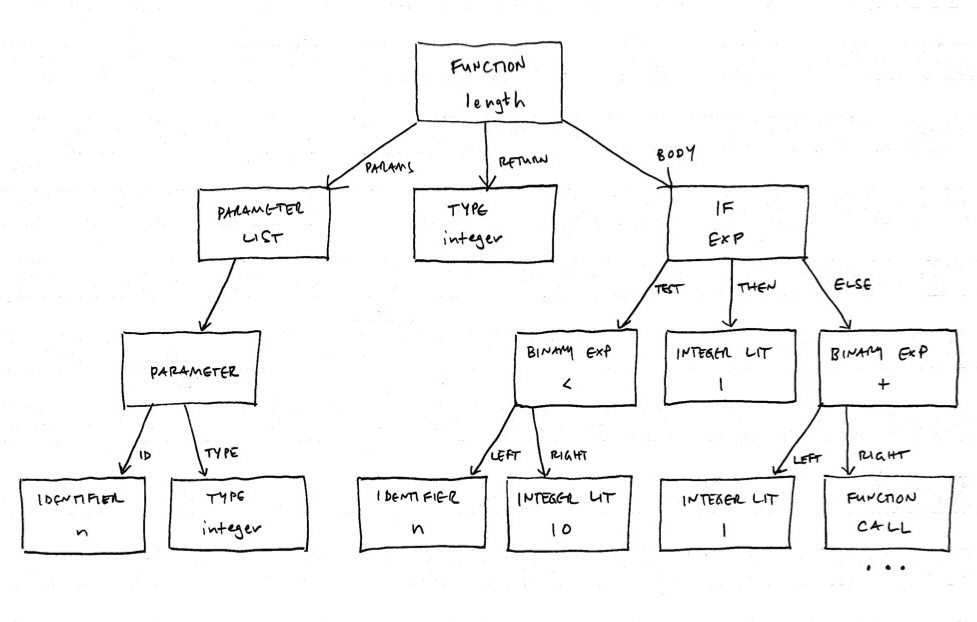

Let's now explore some of the key ideas and techniques behind

type checking. We will use the length function:

function length(n: integer): integer

if (n < 10)

then 1

else 1 + length(n / 10)

and its AST to illustrate the ideas:

Quick review question: Now that the parser has produced an abstract syntax tree, we apply semantic analysis to the AST, not the source code or sequence of tokens. Why?

Type Checking

A type checker verifies that the type of some program component matches what the program expects where the component occurs. Here are some examples of expectations that must be verified:

- Operators expect arguments of a specific type.

- Function calls require a specific number of arguments, each of a specific type.

- Assignment statements require that the value match the type of the variable being assigned.

- Only an array variable can be indexed.

- Only a pointer can be dereferenced.

Type checking can also be of assistance to the code generator. Many target languages, including assembly languages, support different operations for similar but different types, such as integers and real numbers. Knowing that a particular expression is an integer means that the compiler can generate code using the more efficient integer operation.

When an operator such as + can be used with

arguments of different types, we say that the operator is

overloaded. You may be familiar with overloading from

languages such as Java and C++. For example, in Java,

+ works on strings

as well as numbers.

Not only do these languages include overloaded built-in operators, but we can also write methods of the same name that take different types and numbers of arguments. For example, in Java, a class can have multiple constructors, as long as each has a unique argument signature.

In C++, programmers can even overload built-in operators by

writing methods for their classes. For instance, a class for

rational numbers might support addition using the same

+ operator as all other numbers. Or a list class

might support + for concatenation in the same way

as a string. Semantic analysis can identify the context in

which an operator or function operates and record that

information for later use.

To build a type checker, we use:

- information from the language's grammar, which specifies the syntactic constructs that can appear in a program, and

- rules for assigning types to each construct.

For example, the Java language specification says that, when both operands to a binary arithmetic operator are integers, the type of the result is also an integer. This kind of rule points out that every expression has a type associated with it.

The Java spec also tells us that we can create an array of

values by following a type name T with [].

The result is a new type, array of T. This kind of rule

points out that types have structure, because they can

be constructed out of other types.

Type Expressions

In many languages, a type can be basic or constructed.

-

A basic type is one provided as a primitive in the

language, such as

int,char, andboolean. - A constructed type is one created by the programmer, either implicitly or explicitly, out of other types.

For example, an array is typically a homogeneous aggregate of other, and its type reflects that. In languages that support explicit pointers, such as C and Ada, a pointer is a type constructed from another type, too. Just as we can create an array of T for some T, we can also create a pointer to T.

We can also think of the signature of a user-defined function

as specifying a type. For the Klein length

function:

function length(n: integer): integer

A call to length produces an integer value for use

in the calling expression. The function header also creates

an expectation for the call: that it passes an

integer as its only argument. We might think of

this function as having the type:

integer → integer

Compilers that need to reason about higher-order functions, and even verify their types, use function types of this sort. Haskell and Scala are languages that do amazing things with function types, including inferring automatically the types of untyped expressions. But even compilers for more conventional languages such as Java or even Klein can use function types effectively to verify that calls to a function are legal.

Because a type can now be more than just a name, we need to think more generally about type expressions. We will associate a type expression with each language construct that can have a type: identifiers and expressions.

We can specify type expressions more explicitly using this inductive definition:

-

A basic type is a type expression.

Basic types are those provided as primitives in the language. Different kinds of languages offer different kinds of basic types. Typical basic types includeinteger,char, andboolean. -

A type created by applying a type constructor

to one or more types is a type expression.

Arrays and pointers are examples of constructed types with which you are likely familiar. We explore type constructors in more detail in a reading assignment and in the next session. -

A type name given to a type expression is a type

expression.

In C, we can create astructconsisting of parts and name itaccount, soaccountis a type expression.typedef struct { int x, y; } Point;In Ada, we can create new type names explicitly in a program, such as naming an array of numbersHours. This is a type expression, too.

Much more is possible. For example, a type expression might contain variables whose values are type expressions. This is true for generic data types in Ada and Java, and in C++ templates. Consider this C++ template:

template <class T>

T max( T a, T b )

{

return (a > b) ? a : b;

}

The type of max is (T, T) → T, where

T is a type variable. In this expression,

T behaves as a variable ordinarily does —

it has the same value in all three occurrences.

This sort of definition specifies a family of types

that can be instantiated at compile time. In languages other

than C++, Java, and Ada, we could imagine instantiating the

type expression at run-time. Consider the type of a Racket

function like map...

Finally, when we implement a compiler, we often use a special

basic type expression error to indicate

mismatches that arise in type checking.

Type Systems

A type checker assigns a type expression to each expression in a program. The set of rules the checker uses to assign these types is called a type system.

A compiler or another program can implement any type system, even one different from the one specified by the language definition itself. Consider:

- Some compilers provide non-standard features. For example, some Pascal compilers allow a program to pass an array to a function without specifying its index set. This is less strict than the Pascal language definition, so we call such a compiler permissive.

-

Some tools impose style filters on code. As we

discussed earlier,

lintchecks a C program for potential bugs and non-idiomatic style. This can be more limiting than C's language definition. We call such a tool strict.

Of course, we know that a compiler may not do any type checking. However, the fact that the programs in a language are not type-checked at compile time does not mean that the language does not have a type system.

Any feature that can be verified statically can also be verified dynamically, at run time, as long as the target code carries with it the information needed to perform the check.

For example, each object in a program might use a few bits to record its type. At run-time, the interpreter can check types before applying operators, calling functions, or sending messages. This is how languages such as Racket, Scheme, and Smalltalk work. They are strongly typed, but dynamically typed. +

This is one reason that a well-known computer scientist once defined a virtual machine as "a tool for giving good error messages". He might well have said the same thing about a compiler!

The converse is not true. There are some checks that can be done only dynamically in many languages. Consider this Java-like example:

char[] table = new char[256]; int i; // ... later: foo( table[i] );

The compiler cannot guarantee that the attempt to access the

array table[i] will succeed at run-time, because

it cannot guarantee that i will lie in the range

[0..255]. A similar problem arises if we fix the range of

i but allow the program to assign an arbitrary

array to the variable (which is true of Java arrays). In a

language such as Ada, programmers can specify data types much

more rigorously, which enables the compiler to enforce the

definition strictly.

The compiler may be able to provide some help by doing data-flow analysis, another form of static analysis, to infer more about the values that a variable might take. Data-flow analysis can uncover a lot of information about a program, but it cannot check every case that we might like.

What Next?

Our definition of type expressions and our catalog of type constructors give us the tools we need to do type checking. As we will see, most complications in type checking result from constructed and named types. We will pick up our discussion of these issues in type checking next session.