Session 15

An Introduction to Semantic Analysis

Setting Up the Day

Tomorrow marks the middle of the semester, and thus the end of the first half of the course. It has gone quickly! You have learned a lot and are nearing the midpoint of the compiler project.

Today we preview the next unit of the course and take stock of the project. Our activities will be:

- begin to study the next stage of the compiler

- complete a short survey on the state of the project

- break out so that I can meet with each team individually, if desired

Opening Exercise

This Klein program is syntactically correct. A complete and sound Klein parser will accept it and return an abstract syntax tree. But the program does not meet the language specification.

Hint: there is one error in each of the non-library functions.

Finding the Errors

I see five different kinds of error:

-

the wrong type of value given to a primitive operator

not MOD(n, x)

-

a (potentially?) a wrong return type

bit = n

-

a variable that doesn't exist

if (n == 0) ... to_binary(n/2) + MOD(n,2)

-

the wrong type of argument passed to a function

divides(count(true, binary_n), n) divides(count(false, binary_n), n)

-

a wrong return type

apply_definition(to_binary(n), n)

A couple of those may be hard to recognize. Our experience with other languages may mislead us, and some characters look like others.

Remember why this exercise is possible: Our parser uses a context-free grammar to model programs, but Klein — like most languages — is a context-sensitive language. After all the work we've done on our parsers, they accept invalid programs!

Semantic Analysis

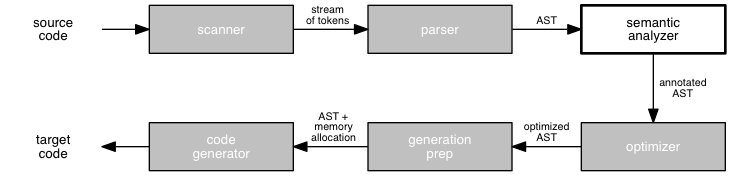

We have just finished studying syntactic analysis of programs and learned how to build a parser that can produce an abstract syntax tree of a program. This tree serves as input to the next phase of the compiler, semantic analysis.

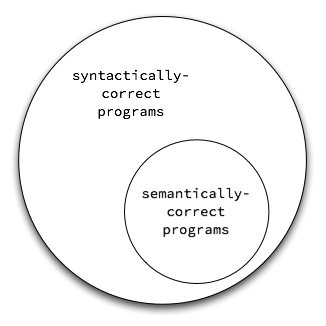

The parser verifies that a program is syntactically correct, which means that it follows the context-free grammar rules of the language. But it cannot tell us that the program is semantically correct, which means that it "makes sense" according to the meaning of the language's constructs. That is the province of semantic analysis.

Much like syntactic analysis, semantic analysis has two primary goals:

- to ensure semantic correctness, and

- to prepare the abstract syntax tree for code generation.

Semantic analysis can also perform a third kind of service:

- to inform the programmer of things that are legal but perhaps unintended.

In this stage, the compiler does static analysis of the program: it verifies only those features that can be observed by looking at a representation of the program. In contrast, there are some features that can be verified only by executing the program, or by simulating its execution. This is called dynamic analysis.

Why not do more dynamic analysis?

Historically, the costs of dynamic analysis have been too high to implement in the typical compiler. In recent years, we have begun to see compilers do more aggressive static analysis in this stage, in an effort to generate more efficient code for more dynamic languages. But with faster computers, some also do dynamic analysis, such as trying all or random values for a variable and running the program to see what happens. As the world changes, we don't want to limit ourselves to solutions from an older world.With static analysis, a compiler can enforce features of a program that are essential in order for the program to be correct but that the parser cannot check. It can also examine features of a program that are not essential to correctness but which programmers might want to know, yet cannot be verified by the parser.

These days, once one has a working compiler, much of the effort in making it better goes into more effective static analysis. It is somewhat ironic that we will only spend a week or so on semantic analysis...

Part of the reason is that we do not have a working compiler yet. Another reason relates to the role of the course in our major: the programming part of basic static analysis is much more straightforward, given your experience working with data structures and tree algorithms. While we have a lot we could se could learn about semantic analysis from a programming languages perspective, we don't have quite as much to learn about it from a software development perspective.

Today, let's introduce the primary goal of semantic analysis, program correctness. Next time, we will consider briefly other goals of semantic analysis and the focus our attention on a specific kind of correctness: checking type correctness.

As we discuss semantic analysis, you may want occasionally to

ask yourself, How many of these features does Klein have?

The answer will give you an idea of what your semantic analyzer

for Klein might be able to do.

Semantic Analysis for Correctness

Static analysis of semantic rules can report errors that are fatal to program execution but which cannot be detected in earlier stages of the compiler. As we discussed in Session 7, some features of a programming language are context sensitive, not context free. A canonical example is matching the number of arguments in a function call to the number of formal parameters in a function definition. A context-free parser cannot make this connection, because function calls happen at a distance, grammatically speaking, from function definitions.

An even simpler example in Klein is using a variable that is out of scope or does not exist at all. Our parser ensures that identifiers are used only in legal locations, but it does not consider which identifiers are being used where.

Rather than ask the parser to process a context-sensitive grammar, which can be expensive and for which we have less helpful theoretical support, we:

- use a simpler context free grammar to model as much of the language definition as possible, and

- specify context-sensitive features as annotations outside the grammar.

This requires a post-processing step after parsing to verify that the rest of the language specification is satisfied.

Here are two Klein length functions that parse

correctly but violate

the language specification":

function length(n: integer): integer

if m < 10

then 1

else 1 + length(n / 10)

function length(n: integer): integer

n = 0

The former uses an identifier that is not in scope. The latter

computes a boolean, but the function is declared as integer.

It would also violate the spec if it returned false

or a call to a boolean function. Semantic analysis must find

all these cases.

What sorts of static features can a compiler reliably check for correctness? Here are a few:

- type correctness of assignments, operations applied to expressions, function calls, and the like

-

correctness of control flow, ensuring that

statements such as

return,break, andcontinuedo not occur outside of the appropriate constructs - initialization of variables prior to use

- uniqueness of identifiers, including labels and the names of functions, parameters, variables, and fields

By tracing the flow of control and data through a program, a semantic analyzer can discover and record a remarkable amount of useful information about a program.

Taking Stock in Project

Whenever I ask questions like "What's not going well?", I always think of this scene from the The Replacements, a 2000 Keanu Reeves movie that is a guilty pleasure of mine.

Not everyone wants to admit that they face challenges, let alone describe those challenges out loud to others. But a project of this scale almost always presents challenges that we have to handle if we are to succeed in building a working piece of software.

Even experienced developers sometimes feel uncomfortable dealing with problems. Don't worry; it is normal. Many professionals have to learn skills for recognizing and communicating challenges.

Share with your teammates, if you are comfortable doing so. If not, feel free to share with me; I have a lot of experience with the feelings from both sides of the table.

One challenge I hear about most semesters is that students often find that they don't know their implementation language as well as they thought they did coming into the course. Again, don't worry; this is normal. Doing projects like this is how we learn, and especially how we go deeper with a language than we ever have before.

Project Survey and Team Meetings

This is a chance for us to talk: to make sure that I'm in sync where your team is and to explore ways we can help you succeed.

While other teams are meeting with me, take a few minutes to answer these questions individually:

- What things are going well for the team?

- What things are challenges for your team?

- What things could I do to help your team?

- What, if anything, stands in the way of completing Project 3 on time?

Your answers to the first two items can be along any dimension: process, tools, teamwork, ....

If you are comfortable doing so, you should probably discuss these questions with your teammates, as well as any other questions you think are valuable. Managing a big project and working as a team bring us new kinds of challenges, and the best way to confront them is usually together.