Session 7

Introduction to Syntactic Analysis

Opening Exercise: Finding Tokens

We have been talking about scanning, and today we talk about parsing. So perhaps you won't mind scanning and parsing a little Java for me.

What is the output of this snippet of code?

How many tokens does the Java scanner produce for Line 6? Line 8?

01 int price = 75; 02 int discount = -25; 03 System.out.println( "Price is " + price + discount + " dollars" ); 04 System.out.println( "Price is " + price - discount + " dollars" ); 05 System.out.println( "Price is " + price + - + discount + " dollars" ); 06 System.out.println( "Price is " + price + - - discount + " dollars" ); 07 System.out.println( "Price is " + price+-+discount + " dollars" ); 08 System.out.println( "Price is " + price+--discount + " dollars" );

If an expression causes an exception, write ERROR

for that line and assume that the rest of the code executes

normally.

See Code Run

Let's compile the code and run it:

$ javac StringCatTest.java

StringCatTest.java:8: error: bad operand types for binary operator '-'

System.out.println( "Price is " + price - discount + " dollars" );

^

first type: String

second type: int

1 error

Ah, an error on Line 04 of the code. Comment it out, compile, and run:

03 | Price is 75-25 dollars 04 | ERROR 05 | Price is 7525 dollars 06 | Price is 75-25 dollars 07 | Price is 7525 dollars 08 | Price is 75-26 dollars

The first thing to recall is that Java's binary +

is overloaded: it performs both numeric addition and

string concatenation. When the left operand to +

is a string, Java's parser chooses the string concatenation

operator. (Well, that's close enough for now.)

The second thing to recall is that both + and

- are also unary operators in Java. In

Lines 5-7, these operators apply to the value of

discount, and the resulting values are printed.

From our discussion of scanning, you should understand why the

+ that follows price in Line 7 is

treated as an operator. Like Klein operators, Java operators

are self-delimiting, so the scanner does not require

that they be surrounded by whitespace.

The scanner knows only that that + is an operator.

How does the parser know to treat it as a binary

operator, not unary? This unit will help us understand how.

The third thing to recall, from as recently as

our last session,

should help you figure out why the Line 8 generates a different

result than the Line 6... The scanner matches the longest token

possible, and -- is also a unary prefix

operator in Java!

What happens if we parenthesize the

price op(s) discount

expressions? Arithmetic ensues.

Do we face any issue like this in Klein? We do. While Klein

does not have + or -- as unary

prefix operators, it does have a unary prefix -

to go with the usual binary operators + and

-. That means that these are legal Klein

expressions, with or without whitespace:

x + - y

x - - y

- x + - y

- x - - y

- - x - - y

but not x - + y. I just gave you

a few test cases for Project 2! Some of these cases are also

ripe for simple optimizations, too...

Feel free to play around with the the original Java program and its parenthesized twin. They are in today's code zip file.

Ironically, these programs grew out of a discussion Prof. Schafer and I had many years ago, after one of his Intro to Computing students asked a question in class — the day before we began our discussion of parsing in this course. The timing was perfect then and perfect now, given that you are writing a scanner and asking questions about negative numbers and expressions without whitespace in Klein. Of course, the CS1 students probably did not appreciate the subtlety of the lexical issues as well you all do.

The Four Levels of Success

As you write your scanners, please keep in mind that there are many levels of success in programming. Here are four levels of increasing success I will consider as I review your code:

- does not compile (or loads with errors)

- compiles (or loads silently), but tests break

- tests run but fail

- tests pass

In an ideal world, all of the tests pass. This can be a challenge when we are writing a large, complex program. We might not even have thought of all the cases we need to test So, we work to make our program a little better each day.

However, we should under all circumstances strive to produce code that compiles, or loads silently, and runs the tests to completion. If our code does not compile, then it has lexical, syntactic, or semantic errors in it. If the tests break, then our code does not satisfy the minimal specification of the task.

When we first learn to program, Level 1 feels like success. However, reaching Level 3 is, as a matter of professionalism, the minimum bar. It shows that we care about our code. Reaching Level 4 is how we succeed.

Module 1: Your Scanner for Klein

How are things going? It is possible! Your state machines will show you the way. Testing the code will help you find bugs that sneak in when our state machines are missing something important. When I wrote my scanner, some tests reminded me that EOF delimits a token, too — but it is unlike other delimiters, which we may need to be part of the next token requested.

To run your scanner, I will cd into your project

directory, follow your instructions to build the compiler, and

then type

kleins /full_path _to_a_klein_program/.

Be sure that this process works before you submit your final

version of Module 1.

$ kleins euclid.kln

That output is different from the output your scanner will produce; more on that soon.

A couple of notes on your scanner:

- The states of your DFAs should be obvious in the code of your scanner, or in its comments.

- Process one character at a time! That is how we ensure correctness and scan the code as efficiently as possible.

What happens if we run the scanner on a program that contains a lexical error?

$ kleins error_case.kln

The client program catches the error and fails gracefully.

Your kleins should, too.

Token Frequency Analysis in Klein

So, I created this thing...

While implementing my scanner, I decided to write a more interesting client program to exercise it. I was curious about which tokens occur most often in Klein programs, and what the relative counts were. If I were inclined, I could use this information to improve my scanner.

So I wrote token_frequencies.py. Its

tally_from(scanner, count_of) function takes two

arguments, a scanner on a source file and dictionary of

token-type counts, and updates the dictionary based on the

tokens in the source file. The rest of the program is

machinery to accept one or more Klein source filenames on the

command line and to count the tokens in all of those files.

When I run my token analysis program on the current set of files in the Klein collection, I get:

$ python3 token_frequencies.py klein-programs/* | sort -r 1614 TokenType.IDENTIFIER 545 TokenType.TYPENAME 545 TokenType.COLON 514 TokenType.COMMA 512 TokenType.RIGHT_PAREN 512 TokenType.LEFT_PAREN 286 TokenType.INTEGER 183 TokenType.FUNCTION 96 TokenType.THEN 96 TokenType.IF 96 TokenType.ELSE 63 TokenType.PLUS 60 TokenType.DIVIDE 57 TokenType.TIMES 54 TokenType.MINUS 53 TokenType.LESS_THAN 52 TokenType.EQUALS 18 TokenType.BOOLEAN 14 TokenType.OR 12 TokenType.AND 8 TokenType.NOT

We notice some good things here: the left and right parens

balance, and every if has a matching

else. So I haven't made those obvious lexical

errors in my Klein programs. Some of the data — say,

the low number of boolean operators or the roughly equal

numbers of arithmetic operators — may be a result of my

style, though some of the programs were produced largely by

former students.

How might we use this information to make a smarter or more efficient scanner?

The Context

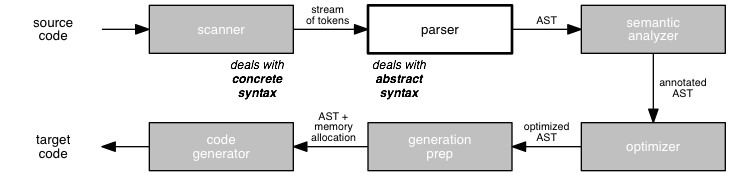

We now turn our attention to syntactic analysis. Recall the context:

The scanner provides a public interface that allows clients to consume the next token in recognizing an abstract syntax expression and to peek at the next token without consuming it. Keep in mind: The parser never sees the text of the program, only the sequence of tokens produced by the scanner.

Regular Languages Are Not Enough to Model Syntax

In our study of lexical analysis, we used regular languages as a theoretical model for the "concrete syntax" of a programming language, its tokens. Regular languages are the subset of context-free languages that do not allow recursion. A regular language can be defined using only repetition of a fixed structure. That suffices for concrete syntax, which has a relatively simple structure.

But the abstract syntax of programming languages requires the full power of a context-free language. Recursion is essential. Consider even this grammar for simple arithmetic expressions:

expression := identifier

| expression + expression

We cannot use substitution to eliminate the recursion, because

each substitution of expression in the + arm

creates a longer sentence — with more occurrences of the

symbol that is being replaced. Repetition is not enough,

because this is not a regular language.

Or consider this little grammar:

expression := identifier

| ( expression )

How can a DFA that accepts this grammar know that an expression

has the same number of ) on the right as it has

( on the left? We can hardcode any specific

number n by adding 2n+1 states to the DFA, but

this grammar allows any number of parentheses. No finite state

machine can be enough.

We saw in our study of lexical analysis that the set of languages recognized by a finite state machine is equivalent to the set of regular languages. So it shouldn't surprise us that, if a regular expression is insufficient for modeling abstract syntax, then a DFA is insufficient for implementing a recognizer for abstract syntax, too.

Recursion is the strength of the context-free languages. Can they serve as our theoretical model for abstract syntax, or do we need more power?

Context-Free Grammars Are Not Enough to Model Syntax, But...

BNF notation is the standard notation for describing languages, and the set of languages describable using BNF is equivalent to the set of context-free languages.

What does context-free mean here? The context in which

a symbol appears does not affect how it can be expanded. In

our first grammar above,

each occurrence of expression in the second

production rule of can be replaced by the right hand side of

any production rule for expression, regardless of

which symbols come before or after expression

in the containing expression.

In our second grammar,

each occurrence of expression in the second

rule of can be replaced with another parenthesized expression.

This freedom makes context-free grammars a tempting solution for describing the syntax of a programming language. However, there are certain constraints we want in our languages that cannot be expressed in a context-free way. Here are two:

- An identifier must be declared or imported before it can be used.

- The number of arguments passed to a function must equal the number of parameters declared for the function.

These rules are sensitive to the context in which the constrained token appears. For a call to a function with two arguments to be legal, the function must be declared elsewhere to accept two arguments. A grammar that captured such a constraint would have to have rules with more complicated left hand sides. Consider:

S := sAt

| xAy

sA := Sa

| b

Ay := SaS

| b

The left hand side of the second rule requires that it be used to replace As only in conjunction with preceding s's. The third rule applies only when an A is followed by a y.

In a context-sensitive language, the left hand side of a rule can specify context information that restricts a substitution. This enables us to represent more elements of a programming language than a context-free language, including the practical constraints listed above.

Unfortunately, processing a context-sensitive grammar is considerably more complex and considerably less efficient than processing a context-free grammar. When writing compilers, these costs are not worth the benefits they bring, because they apply to only a few isolated elements of programming language syntax.

So: we will use a two-part strategy to recognize programs at the syntactic level:

- use a context-free grammar to model the abstract syntax of a programming language, and

- perform semantic analysis of the parser's output to enforce the context-sensitive rules of the language.

This means that, strictly speaking, the set of programs accepted by a context-free parser is a superset of the set of valid programs. An invalid sequence of tokens can pass the parser successfully.

Building a Machine that Recognizes Programs

When we move from describing lexical information to describing syntactic information, we generalize from regular languages to context-free languages.

Likewise, when we move from recognizing tokens to recognizing sentences, we generalize from a finite-state machine to a set of finite state machines. Each machine can call the others — and itself. That's recursion!

In order for this process to work, the state of the calling machine must be resumed when the called machine terminates. To do this, the parser must save the state of the calling machine. The machine calls are nested, which means that a stack can do the trick.

Just as regular languages find their complement in finite state machines, so, too, do context-free languages find their complement in pushdown automata. Because a pushdown automaton provides an arbitrarily deep stack, it is able to handle nested expressions of arbitrary depth.

Like FSMs, the topic of pushdown automata is understood so well that the theory of computation can help us write programs that recognize context-free languages. We call these programs parsers. The same theory that helps us write parsers also enables us to generate parsers automatically from grammars.

Deriving a Program Using a Grammar

We use BNF to write a context-free grammar for a language. The terminals of the grammar are tokens, and the non-terminals are the abstract components of programs.

You are working closely with such a context-free grammar as you build your compiler, that of the Klein programming language. As another example, take a look at the grammar for Python 3. Notice the format of this grammar: it can be read by a Python program! (You might consider creating a "readable grammar" for Klein...)

There are several ways to think about at how a grammar defines the sentences in its language. One particularly useful way is derivation, in which we construct a sequence of BNF rule applications that leads to a valid sentence. Derivation is closely related to the substitution model used to evaluate expressions in functional languages such as Racket.

Derivation treats the grammar's production rules as rules for rewriting an expressions in an equivalent form. Consider this more complete arithmetic expression grammar:

1 expression := identifier 2 | expression operator expression 3 | ( expression ) 4 | - expression 5 operator := + | - | * | / | ^

We can use this grammar to derive the sentence

-(identifier + identifier) in this way:

expression => -expression using rule 4

=> -(expression) using rule 3

=> -(expression operator expression) using rule 2

=> -(identifier operator expression) using rule 1

=> -(identifier + expression) using rule 5a

=> -(identifier + identifier) using rule 1

The theory underlying context-free grammars and derivation is understood well enough that we can do induction proofs to show that:

- any sentence in a language can be derived from its grammar, and

- any sentence that can be derived from the grammar is in the language.

We will use these ideas to drive our construction of parsers. They will use derivation of a sentence as a model.

At each point in a derivation, we generally face two choices:

- which non-terminal to replace

- which rule to use when doing so

In the derivation of -(identifier + identifier)

above, I always chose the leftmost non-terminal as the symbol

to replace. The result is called a left derivation.

Similarly, I could have generated a right derivation by always choosing the rightmost non-terminal to replace:

expression => -expression using rule 4

=> -(expression) using rule 3

=> -(expression operator expression) using rule 2

=> -(expression operator identifier) using rule 1

=> -(expression + identifier) using rule 5a

=> -(identifier + identifier) using rule 1

Does it matter which of these selection rules we use, or if we use some other rule? Let's see.

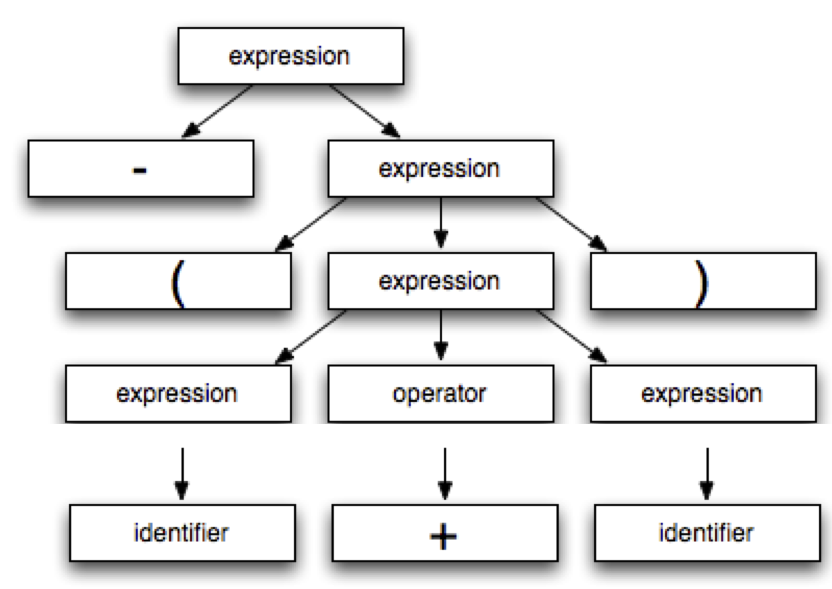

Parse Trees

We can use derivation to generate a tree that shows the

structure of the derived sentence. This is called a parse

tree. The parse tree for

-(identifier + identifier) looks like this:

Parse trees are useful as intermediate data structures in syntax analysis and also as the motivation for parsing algorithms.

Quick Exercise: Draw the parse tree for a left derivation of this sentence:

identifier + identifier * identifier

Here's a solution:

expression

/ | \

expression operator expression

| | / | \

identifier + / | \

/ | \

expression operator expression

| | |

identifier * identifier

I created it by expanding the left expression

using Rule 1 of the grammar.

expression => expression operator expression using rule 2

=> identifier operator expression using rule 1

=> identifier + expression using rule 5a

...

But wait... Here is a parse tree for another left derivation of the same sentence:

expression

/ | \

expression operator expression

/ | \ | |

/ | \ * identifier

/ | \

expression operator expression

| | |

identifier + identifier

I created this one by expanding the left expression

using Rule 2 of the grammar, instead of Rule 1.

expression => exp op exp using rule 2

=> exp op exp op exp using rule 2

=> identifier op exp op exp using rule 1

=> identifier + exp op exp using rule 5a

...

Recall that, at each point in a derivation, we may have two choices to make: which non-terminal to replace and which rule to use. The left/right derivation process fixes the choice of non-terminal, but we still have to choose a rule to use. Sometimes, more than one rule applies.

We now see that the choice of rule does matter. Different rules can produce different parse trees. We can also see the value of using a tree to record a derivation: it demonstrates the structure of a derivation more readily than a text derivation.

When the same sentence has two different but valid parse trees, we say that the grammar is ambiguous. Theoretically, this sort of ambiguity may not matter much, but practically it matters a lot.

In our next session, we will consider why ambiguity matters and then look at ways to eliminate ambiguity from a grammar before building a parser.