Session 26

Code for Generating Target Code

Producing Better Error Messages

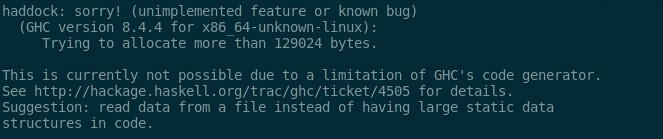

A few years back, a compiler researcher tweeted a snapshot of a compiler error message from the Haskell world:

This message contains two very nice bits of text:

- "(unimplemented feature or known bug)"

- "This is currently not possible due to a limitation in GHC's code generator."

If you still have bugs or unimplemented features in your code generator when you submit Module 6, either of these phrases can serve as the basis for a good error message. You could even point readers to your project's README file!

As you have learned, generating good error messages in the face of lexical, syntactic, and semantic errors is difficult. The machinery of a compiler rarely matches the mental model of the programmer.

How can we do better? If you are interested, check out the details box. The takeaway idea is both simple and not especially difficult to implement. Like so many good ideas, it just takes time.

Generating Targeted Error Messages

This blog entry introduced me to this research paper, which contains a really cool idea for a way to do better. The paper describes a program that takes as arguments:

- a list of syntactically incorrect programs, and

- a list of error messages for each of them

It then figures out the parser states that cause the error in each program. The error entry for that state in the parse table can then be modified to print the corresponding message. This program automates error message generation from examples!

We are not likely in any position to write such a tool this semester, but that doesn't mean we can't learn from the idea. The Klein program directory contains error test cases for our lexical, syntactic, and semantic errors. We could...

- write the perfect error message for each test case,

- modify the checker temporarily to print its state on an error, if it doesn't already,

- run each test case against the checker see what state the test causes,

- modify the checker to look up the error message when it reaches an error state.

One way to implement this would be to have the scanner and parser maintain a separate dictionary that maps error states onto error messages. Another would be to record the parser's error messages in the parse table.

Even with a pretty good set of Klein test cases, this would not take all that long, and the benefit in the usability of our compiler would be immense. Consider this as a possibility when we get to Module 7 and you have an opportunity to make an improvement to your compiler.

Of course, automating the process, as the research paper that inspired this idea did, is just what a computer scientist would think to do!

Where We Are?

We have been looking at ways to generate target code from an

intermediate rep or an abstract syntax tree. Last session,

we generated 3AC and assembly code for

a specific if expression

that served as an exemplar for a more general code template,

examined

a simple algorithm

for generating target code, and considered some

techniques for selecting registers

to use in a code template.

In those activities, we can find at least two lessons:

- If we are not concerned with the size or speed of our target code, we can generate assembly code for basic operations in a straightforward way with surprisingly little effort: load data into registers, operate on it, and write data back to memory.

- If we would like to generate more efficient code, there are a number of small modifications we can make to the basic algorithm. These require the generator to store data that help it make better decisions: a register map, information about each object's next use, or both.

If we really care about efficiency, we could create a whole new course out the things we haven't learned yet.

This time, we wrap up our discussion of code generation with one item that completes the story from last time:

- a more detailed look at how to use "next use" information, including a little exercise to experiment with the idea — and to create code that you can use in your own project.

And two pragmatic items to help you with your code generator:

- a look at some of the issues involved in generating code for functions and function calls. This may seem more complex, but at one level it's quite similar to techniques for other statements: we create a template for each of the activities required.

- a quick look at a tiny example, Louden's code generator for his Tiny C language. It will show us that most features of Klein can be handled using the simple techniques we have been learning.

Using Next Use Data in Register Selection

Collecting "next use" information enables the code generator to

produce much more efficient code. Here is an algorithm to

select a register for x in the instruction

x := y op z, taking advantage of "next use"

information:

-

If

yis in a register that holds no other values andyhas no next use, then:-

update the register map to indicate that

yis no longer in the register, and -

return

y's register.

z. -

update the register map to indicate that

- If there is an empty register available, then select one of them.

-

Find an occupied register

R, preferably one holding objects that have no next use. Store the value inRto the memory location(s) associated with those objects. Update the register map to indicate thatxis now inR, and returnR.

TM requires that all arithmetic operations be done on registers. Not all machines do. If a target machine allows operations on memory locations, we can add a Step 4 to our algorithm that doesn't return a register at all:

-

If no registers are available, select the memory

location of

xas the target.

Memory operations are usually much slower than register operations, so many compilers reserve this as a last option. However, there may be circumstances in which this step might be preferred to Step 3, in order to save storing and re-loading another object.

Let's consider how getRegister() might work when

generating code for this example:

k := (i + j) - (i + h) - (i + h)

Let's assume that h, i,

j, and k are in memory locations

0, 4, 8, and 12, respectively, past the status pointer (R5).

| STATEMENT | CODE GENERATED | REGISTER MAP |

|---|---|---|

t1 := i + j |

LD 1, 4(5)LD 2, 8(5)ADD 3, 1, 2

|

(R1: i)(R3: t1)

|

t2 := i + h |

LD 2, 0(5)ADD 4, 1, 2

|

(R1: i)(R2: h)(R3: t1)(R4: t2)

|

t3 := i + h |

ADD 1, 1, 2 |

(R1: t3)(R3: t1)(R4: t2)

|

t4 := t1 - t2 |

SUB 3, 3, 4 |

(R1: t3)(R3: t4)

|

t5 := t4 - t3 |

SUB 3, 3, 1 |

(R3: t5) |

k := t5 |

ST 3, 12(5) |

(R3: t5, k) |

Note that...

-

In the second and third steps, the code generator can take

advantage of the fact that

iis already inR1. -

In the third step, the code generator can take advantage of

the fact that

iis inR1but has no next use in the code block. -

In the first step and all steps beginning with the third,

the code generator can take advantage that some items in

registers do not have next uses, so the register can be

freed. The first dead object is

j, inR2for the first addition.

Because k is live at the end of this block, the

code generator stores its value into memory. That way,

downstream statements can load the correct value for

k when needed. The code generator could be even

more efficient by maintaining a memory map that shows

the current location of each object's value. In this way, it

can allow k's location in memory to be out of

date across templates.

There are many other strategies for improving efficiency that a code generator can use when allocating registers. For example, it might identify an object that is used frequently in the block and make a global assignment of a register to that object. On machines with plenty of registers, this approach can work quite nicely.

"Plenty" is relative to the kind of source code being translated. For example, functions in a pure functional programming language tend to be small, because those languages don't allow sequences of statements. As a result, the number of objects used by any given function tends to be small. So a target machine with even a small number of registers may make global assignment feasible.

Even in a language like Klein, we can sometimes use fixed

register assignments for a chunk of code. Consider, for

example, the divisibleByDifference function in

the divisible-by-seven program

from the Klein catalog:

function divisibleByDifference( diff : integer ) : boolean

if ((diff = 7) or (diff = 0) or (diff = -7) or (diff = -14)) then

true

else

if diff < 14 then

false

else

main(diff)

The parameter diff is is used seven times

throughout the function and never changed. Parking it in a

register will simplify the generated code.

Even from this short discussion, using the two simple extensions introduced above, you can see that what the 'red' edition of the Dragon book says is true. Paraphrased:

A great deal of effort can be expended in implementing

[the getRegister() procedure]

to produce a perspicacious choice.

"perspicacious" — wut?

"perspicacious" is a great old word. Check it out! . :-)For your compiler, make choices that are simple enough for you to implement but detailed enough for you to generate code you are proud of. Start with simple code that works and add features as you have time.

Exercise: Computing Next Use Information

Computing next use information is not all that difficult.

Let's assume that we are using quadruples of the form

[operator, arg1, arg2, result] to represent 3AC

statements, as we saw in

Session 23.

A 3AC program can be a list of quadruples. In Python, we

might have something like this:

program = [ [t.NEGATE, 'c', t.EMPTY, 't1'], # t1 = - c

[t.TIMES, 'b', 't1', 't2'], # t2 = b * t1

[t.NEGATE, 'c', t.EMPTY, 't3'], # t3 = - c

[t.TIMES, 'b', 't3', 't4'], # t4 = b * t3

[t.PLUS, 't2', 't4', 't5'], # t5 = t2 + t4

[t.COPY, 't5', t.EMPTY, 'a' ] ] # a = t5

Note that the uses are in columns 1 and 2.

nextUse(identifier, program, currentLine).

nextUse returns the next statement

after statement currentLine that

uses identifier.

If identifier has no next use, return -1.

For example,

>>> nextUse('c', program, 0)

2

>>> nextUse('t1', program, 1)

-1

Feel free to write your code in Java, Racket, or any language you like. Assume a list in the appropriate form for that language.

Solution

Take a look at

my sample solution,

along with some simple test cases. Look how easy it is to

find the next use of a variable in a 3AC program! You

can implement an efficient

getRegister() function

using a function just like this.

Computing next uses from a given program line is easy, but doing it repeatedly seems wasteful. If you decide to go this route, you may want to compute all of the next uses of each identifier upfront. You can then store them with the identifier's entry in your symbol table, or in a new data structure in your code generator. My solution file contains a sample function that does this, too.

As complex a beast as a compiler is, many of the components we need are relatively simple to implement. Take heart!

Generating Code for Functions

Consider how we might translate this Klein function:

function double(n: integer): integer

2 * n

... into three-address code:

ENTRY double t01 := 2 t02 := n t03 := t01 * t02 RETURN t03 EXIT double

We can use 3AC instructions such as ENTRY and

EXIT to mark the boundaries of the function in a

program. Knowing these boundaries helps the code generator

perform several of its activities, including:

- determining the size of the target code, which is needed in order to compute the appropriate addresses to branch to and from

- determining where a block ends when deciding whether a variable or a register has another use in the block

Most importantly, ENTRY and EXIT

serve as signals to generate the called functions's portions

of the

calling

and

return

sequences. The TM templates for these instructions can

provide generalized versions of the two sequences.

When the code generator encounters a function definition, it must generate code for the body and store it in the selected location. Often, this is in the static section of the target code. But the target location could be in a temporary object stored on the stack or heap. Then it must record that location with the function's name in the symbol table.

In TM, of course, the code is written to the next region of IMEM.

Now consider this Klein expression, which calls

double:

if (threshold < double(count))

then value

else value*count

... which translates into this three-address code:

t01 := threshold BEGIN_CALL ; — these four lines PARAM count ; — implement CALL double 1 ; — t02 := double(count) RECEIVE t02 ; — IF t01 ≥ t02 GOTO label_one ; invert test to jump then t03 := value GOTO label_two LABEL label_one t04 := value t05 := count t03 := t04 * t05 LABEL label_two [ ... return or use t03 ... ]

The code template for CALL must implement the

caller's side of calling sequence. Who or what is responsible

for the caller's side of the return sequence? The code

template for CALL might be responsible for that

as well!

That shouldn't be too surprising. To the calling code, the

call and the return look like a single unit of computation.

When the called function branches back, the very next thing

to do is handle the return value and continue. We could even

create a CALL operator in 3AC that takes the

location of the returned value as one of the three addresses,

say CALL double 1 t02 or

t02 := CALL double 1.

Consider what the calling sequence part of

CALL double might look like:

return_address := (contents of r7) + (size of this code) * * allocate an activation record for double * ... size = 1 + 1 + 1 + 6 + 3 * * evaluate args and store in activation record * LD r1, count ST r1, argument slot of activation record * * store return address * LD r1, return address ST r1, return address slot of activation record * * store status and top pointers * LD 5, fifth slot in register region of activation record ST 6, sixth slot in register region of activation record * * branch to double * LDC 7, address of double

(What do the other three templates for the calling and return sequences look like?)

If the compiler uses a register to hold its return values, then these templates change a bit. As we've discussed, this choice makes a tradeoff of using less stack space for potentially slower programs: Fewer free registers may mean writing temps to memory more frequently. Then again, if our templates save objects immediately to memory anyway, we are already paying that price.

Louden's Tiny C Code Generator

For some ideas of how to implement parts of a code generator, let's consider an example from the creator of TM. In his textbook, Louden implements a compiler for Tiny C, a subset of the C programming language that includes assignment statements and global variables but not functions. (He leaves functions as an exercise for the reader.) His implementing language is also C.

The code generator consists of two modules, code

and cGen.

The code module implements functions for emitting

the various kinds of TM instructions.

code.h

gives headers for these code-emitting functions, but it also

defines aliases for a number of registers, including:

-

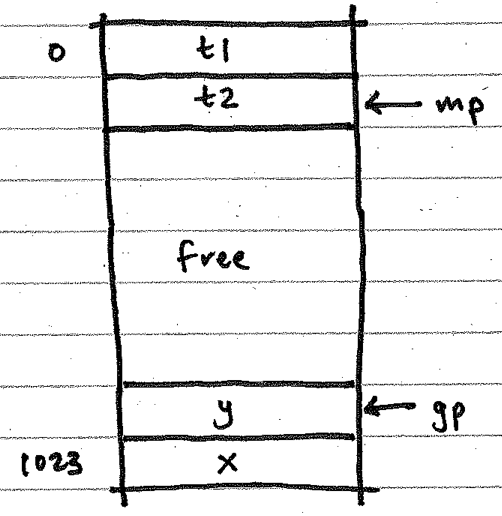

gp, a pointer to the top of the stack in data memory where global variables are allocated, and -

mp, a pointer to the top of the stack in data memory where global temporaries are allocated.

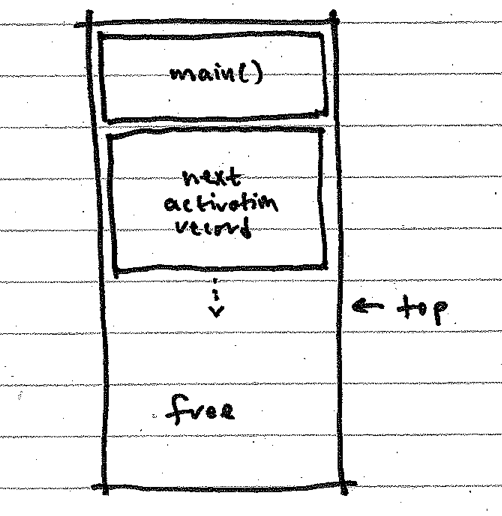

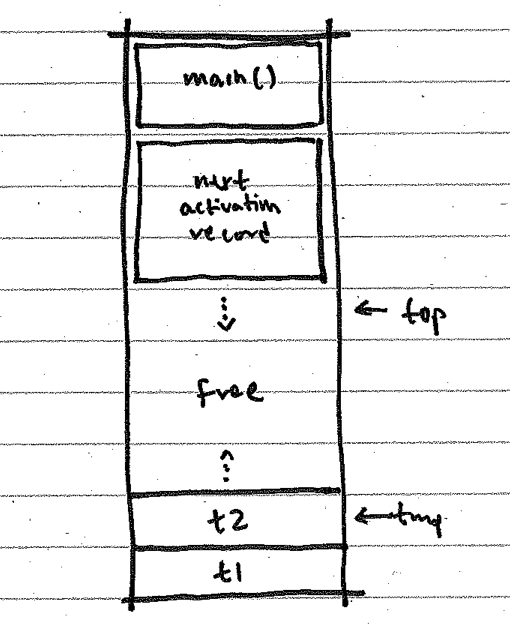

This works for Tiny C because it has no need for a stack of activation records. Klein, on the other hand, has functions but no global variables. It does have command-line arguments, though, that are stored initially at the bottom of data memory. You could base your activation stack at the first free slot past the base values and let the stack grow upward:

However, you have many options when implementing data memory in your compiler. For instance, you might allocate any number of the temporary variables used by your run-time system at the top of the memory, and let your stack grow toward them from the bottom:

Louden uses two of TM's registers, 5 and 6, to store Tiny's memory pointers. He then uses two more registers, 0 and 1, as the working space for all of his code generation routines. He never uses registers 2, 3, or 4 at all! They are all "0 registers". Again, the best parts of his compiler are left for his readers to implement as part of a project.

code.c

defines the methods that generate the various kinds of TM

instruction, including RO instructions,

RM instructions, and TM comments. These are

called from the code generator itself, which now doesn't have

to worry about the format of instructions, instruction memory,

or issues related to debug utilities. Louden handles jump

targets in a more complex way than we saw

in our example

last time and so has a larger set of functions for the process.

The cGen module defines the code generator

itself, a procedure named codeGen. The public

interface to the generator is specified in the

cgen.h

header file. When we examine the implementation file

cgen.c,

we see that codeGen is an interface procedure.

It produces standard code at the beginning and end of the

target file, wrapped around a call to cGen, the

procedure that does the real work.

cGen itself is pretty simple. It uses structural

recursion to examine its argument, a tree node, and calls the

appropriate helper method to generate assembly instructions

for each of the kinds of statement and expression in Tiny C.

Here are two code samples:

-

the template for expressions with binary operators,

y op zp1 = tree->child[0]; /* node for left arg */ p2 = tree->child[1]; /* node for right arg */ cGen(p1); /* code for left arg */ emitRM("ST",ac,tmpOffset--,mp,"op: push left"); /* push left operand */ cGen(p2); /* code for right arg */ emitRM("LD",ac1,++tmpOffset,mp,"op: load left"); /* reload left operand */ switch (tree->attr.op) { case PLUS : ... case MINUS: ... ...The generator has to "push" and reload the left operand becausecGenuses the same two registers to do all of its work, the ones aliased asacandac1. -

the sub-template for the less-than operator,

y < zemitRO("SUB",ac,ac1,ac,"op <") ; emitRM("JLT",ac,2,pc,"branch if true") ; emitRM("LDC",ac,0,ac,"false case") ; emitRM("LDA",pc,1,pc,"unconditional jmp") ; emitRM("LDC",ac,1,ac,"true case") ;Recall from above that the left operand is now inac1, and the right operand is inac.

The idea for our project is the same, even if the code is different. You will want to create a code template for each kind of expression in Klein. Louden's templates can often serve as examples from which to work, if you'd like.

Louden's code generator offers a good demonstration of how you

can use abstraction layers to simplify a complex piece of code.

codeGen is made easier to understand by deferring

the statement-specific complexities to cGen.

cGen itself is made simpler by using helper

functions to produce the strings that make up the target

program.

Does this approach make it easier to generate target code for another machine? Why or why not? If not, could we do anything to make the generator easier to re-target?

In closing, recall that all of the code for Louden's compiler is available from his website and also as a local mirror in the Course Resources folder. If you would like to look at just the code generator files, you can grab these files which are included in this session's zip file.

In Closing

The Project

Your project, in particular the code generator, is your only task at this point in the course. It will take time for you to write a complete code generator, but the effort is worth it. You will eventually see your compiler produce TM code from a Klein program, and we will watch the TM code run!

Module 7

The code generator is due at the end of Week 14. This gives you a week to fix errors, clean up your code, prepare your final project submission, and improve the compiler in some way (optimize some part of the code, produce better error messages, etc.). We'll discuss this more after break.

Final Sessions

After break, we have four sessions. I have a couple of things I plan for us to talk about, especially the one part of a compiler we have bypassed thus far: optimization. I can think of many things we might look at, among them virtual machines, garbage collection, and what it would take to expand the Klein language and our compiler.

What would you like to learn about? Please include a note in your status check this week letting me know what you would like to do in those final sessions.