Session 30

Course Wrap-Up

Final Opening Exercise

In lieu of Homework 11, let's use a little class time to reflect on language design and compiler construction.

Compilers in the World

A Little History

Sixty-nine years ago, a team at IBM changed the computing world forever when it published the first programmer's reference manual [ PDF ] for Fortran, "The IBM Mathematical Formula Translating System". Fortran was simultaneously a high-level programming language and a program that translated programs written in the new language into the machine language. A compiler.

Just think: the first commercial compiler was created around the time your grandparents were born. (My mom was not yet a teenager.)

The idea itself isn't much older. The first compiler of any kind was written by Corrado Böhm in 1951 for his Ph.D. dissertation, long before computer science programs existed at universities. But the academic study of computer science was already taking off. Soon students were required to learn how to write a compiler as a part of their undergraduate studies. The compiler was both a necessary tool and one of the two or three essential pieces of system software that every computer scientist needed to understand.

Some university CS departments began to drop their compiler writing courses twenty or thirty years ago. As the discipline grew, so grew the demands on the undergraduate curriculum. Compilers had become so common that they could be taken for granted as infrastructure, and for a while it seemed that not many new languages were being created.

Resurgence

But the 1990s saw a resurgence in the creation of new languages that has continued through today, from Lua, Python, and Ruby to Scala, Rust, Zig, and Elixir. When programmers create a new language, they have to build compilers, editors, debuggers, and profilers. Building these tools requires compiler technology.

Sometimes, programmers want to re-target a huge mass of existing code to a new platform (say, from Java to Javascript), so they build tools like the Google Web Toolkit to automate the port. Or maybe they want to help programmers using an existing language work in a new environment. Continuation Passing C (CPC) is a relatively new language that was designed for writing concurrent systems more reliably in a C environment. Building these tools requires compiler technology.

And, yes, some programmers want to make their mainstream languages better or more widely useful. Take Ruby, for example. In an interview fifteen years ago this month, Chad Fowler talked about the diversity of Ruby compilers available at the time:

There's Matz's Ruby (1.8), YARV (1.8 + a new VM and syntax for 1.9), JRuby, Rubinius, Maglev, IronRuby, MacRuby, Rite, and others in development. All of them can run real Ruby code. All of them provide advantages over the others. Each implementation is faster for some things than the current state-of-the-art canonical Ruby implementation.

Since then, Ruby 1 and Ruby 2 have reached their final resting place, and Ruby 3.3.10 has been released. Programmers never sit still for long.

Building these compilers... well, that requires building a compiler.

Self-Hosting Compilers

For many programming languages, the ultimate test is to become "self hosting". One of the best ways to demonstrate that a language is ready for prime time is to write a compiler for the language in that language itself, and then use to use the compiler to compile itself.

This serves as a test of the language's features, of course, but it also has a practical effect: it makes it possible to port the compiler to a new target machine by writing only a new code generator and compiling it with the existing compiler!

The first self-hosting compiler was NELIAC, a dialect of ALGOL 58, though:

- Lisp is better known for being self-hosting in 1962, and

- Böhm — again — had defined the compiler for his 1951 PhD dissertation in the very same language it compiled. Impressive.

Of course, this creates a "chicken and egg" problem that we considered back in Session 3. Do you remember this image?

What does this diagram show?

This idea is not simply a theoretical exercise. The same process is used to build first compilers all the time. One of my favorite stories is this write-up by the creator of Guile, an embeddable scripting language, who bootstraps his entire compiler from one interpreter file and the barest of C interpreters:

In the end, though, you have to have a Scheme compiler to compileeval.scmitself, so we do end up keeping around an evaluator in C. Its only purpose is to interpret the compiler, so we can compileeval.scm: then the compiled version ofeval.scmcompiles the rest of Guile, including the compiler.

And here's a wild digression, beyond the content of this course, but perhaps in its spirit: Bootstrapping is not just for programmers any more.

And Then There Was Klein...

What is the smallest set of features we would have to add to the Klein programming language to make it powerful enough to write a self-hosting compiler in Klein?

While we are fantasizing about Klein, here are two more fantasies:

I think it would be way cool to build a random Klein program generator a lá Csmith, both for testing our compilers and for kicks.

Could we morph our table-driven parser into a table-driven code generator?

Instead of compiling to TM, how about if we target wasm, "a binary format to run programs at native speed in the browser"? Wasm has already begun to disrupt end-user apps as we know them, from MS Office to Photoshop to games.

A professor can dream, especially at the end of the semester.

The Final Recap

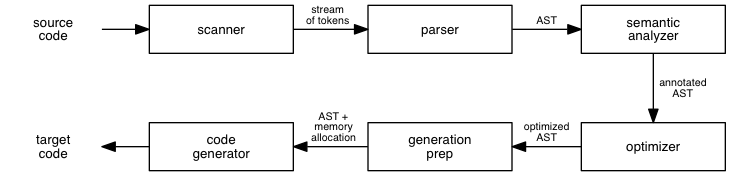

We have learned about the analysis phase of a compiler: taking a program written in a source language as a stream of characters, doing lexical analysis to generate a stream of tokens, doing syntactic analysis to produce an abstract syntax tree, and doing semantic analysis to ensure that the AST satisfies the language definition.

We have learned about the synthesis phase of a compiler, which converts a semantically-valid abstract syntax tree into an equivalent program in the target language: building a run-time system to support the execution of the target program, translating the AST through one or more intermediate representations such as three-address code, translating the final intermediate representation into code in the target language, and optimizing the code.

This made for a busy semester. On top of all this, you wrote a compiler of your own.

There is far more to learn about compilers and writing them. But take heart. Eli Bendersky has written a series of excellent blog posts on building a just-in-time compiler. In the final article of the series, he writes:

LLVM's ORC JIT looks formidable, but there's no magic to it. In its essence, it's just doing the thing my introduction to JITing describes, with many (many!) more layers on top.

This sentiment generalizes to what you have learned this semester. There is no magic to building a bigger, better compiler, just many more layers — and time. The magic is in the result, a system of many parts working together to perform an impressive task.

As much work as this course turned out to be, I think you probably learned an awful lot from writing such a large and complex program. In fact, that is probably the only way that we can really learn how to program.

Compiler Writing as Software Development

Introduction

Software engineering is what happens to programming when you add time and other programmers.

I'm sure you understand now, better than ever before, why this course satisfies the project requirement for the Computer Science major.

Our goal for the project courses is for students to have an experience using modern tools in a setting that is much like the "real world" as we can simulate in a fifteen-week course. These courses give you a significant project to include in your portfolio.

For all of the technical content of this course, writing a compiler is, at its core, a software development project. All of the issues that matter when we write any other large program matter when we write a compiler. Consider a few.

Project management

Project management has a huge effect on the implementation of any project as large as a compiler. This includes project planning, collaboration among teammates, and managing the work of a team of developers.

Programming Tools

Software developers depend on the quality and support of the programming tools they use. The same is true for compiler writers. These tools include the programming language used to implement the compiler and support tools such as IDE, profilers, build management tools, version control systems, scanner and parser generators, and more.

Testing

Testing is an essential component of any software development project. How did you test your compiler? Did you have a suite of test programs that exercised all of the important features of your scanner, parser, semantic analyzer, and code generator? Did you have any way to run your tests automatically?

Changing Specifications

Finally, software projects typically face the problem of changing specifications over time. Compiler developers must deal with the volatility of changes to the source language or target language. Klein and TM remained the same over the course of the semester, though we made two clarifications:

-

defining what

MAXINT()+1means - learning how TM represents booleans

But even mature languages such as Java and Python can undergo significant changes. Target machines evolve, too: The Java virtual machine, the target machine of choice for so many languages, underwent a major change of its own a few years ago.

Teamwork

Working with other people makes you more hirable!

We often think of "working on a team" as a skill that we need to work in industry. And it is something that we can practice and get better at. But there's more: working with other people makes us better programmers.

... a candidate who'd worked with lots of other people had been exposed to more code, more dilemmas, more challenges (technical and human), and they were not just more ready to work on a larger team but more knowledgeable. Even their individual skills were greater.

Hat tip to Brent Simmons.

Reinventing the Wheel

Yes, we reinvented the wheel this semester. The ground we covered in this course is well-understood. We did not work at the cutting-edge of compiler development.

There are many good reasons to reinvent the wheel. Here are three that are important when people :

- learn how wheels are made

- learn the tools needed to make wheels along the way

- learn a tiny slice of what it means to build a larger system

There are also good reasons to reinvent the wheel after you know a lot about wheels. Maybe you would like to build a better wheel. Maybe you want to be able to fix wheels when they break.

Reinvent for insight. Reuse for impact.

Hat tip to Matthias Endler.

Followup Questions

Did CS 3730 help? We could always spend more time in this course learning specifically about software engineering and project management, though that would mean eliminating some compiler material. Maybe what we need most is closer monitoring of the teams; most of you learn about software engineering best by writing a big program with a few other programmers.

How much did the software engineering aspect of this project affect your success? How much did the compiler content affect your success? How much was it the programming itself?

The Final Countdown

Our next session is the final exam period. As the course home page tells us, we won't have a final exam, but we will meet.

We will do three activities during the exam period:

- The teams will present their final projects.

- Individually, you will evaluate the other teams' presentations, your team's project, and the performance of your team.

- I will present some summary statistics about your compilers and about how they run, including on one or more new Klein programs.

Then, we part ways and enjoy our accomplishments.

See the specification page for more detail on the presentation and evaluations.

One quick note: Please demo the version of your project you submit as Module 7 unless you (1) get approval from me first and (2) explain the improvements you made after the official submission during your presentation.

See you next week!