Session 28

Code Optimization

A Quick Challenge: Improve a Loop

Introduction

Consider this little snippet of C, which operates on a string

str. Let's assume that str is

really long.

for (int i = 0; i < strlen(str); i++) {

process(str[i]);

}

Last time, we learned that most compilers will generate more efficient code by "unrolling" the loop:

for (int i = 0; i < strlen(str); i+=5 ) {

process(str[i]);

process(str[i+1]);

process(str[i+2]);

process(str[i+3]);

process(str[i+4]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < strlen(str); i++) {

process(str[i]);

}

A New Loop Optimization

The strlen() function is called

strlen(str) times! In C, this is especially

costly, because strings are zero-terminated arrays of

indeterminate length. As

James Hague points out,

we have an unintentional O(n²) loop!

So, our compiler can optimize the loop by making the call once before entering the loop:

int len = strlen(str);

for (int i = 0; i < len; i++) {

process(str[i]);

}

This is an example of a more general class of optimizations: move loop-invariant code outside of the loop. This is sometimes called code hoisting.

Alas, in the case of C function calls, the compiler may

not be able to move the call to strlen(str).

Hague notes:

As it turns out, this is much trickier to automate than may first appear. It's only safe if it can be guaranteed that the body of the loop doesn't modify the string, and that guarantee in C is hard to come by.

str is a pointer, and process()

might modify the string. Hague gives a bit more on why it

it can be hard to prove that process() doesn't

modify the string.

Freedom to Improve Code

Depending on the semantics of the source language, even simple improvements to code can be hard to implement automatically in a compiler. This helps us appreciate even more the ways in which compilers do optimize our code.

Note that this particular issue — does the loop modify the string? — is less of a problem in Java, because a string is an immutable object that stores its length in an instance variable.

Even without the O(n) walk down the string to find the

string's length, though, this optimization yields substantial

savings. Check out

this Java file.

The len-optimized loop runs 4-5 times faster for

the short string and ~2 times faster for the much longer

string. Here's a typical run:

| original version |

optimized version |

|

|---|---|---|

| short string |

3958 | 1084 |

| long string |

840583 | 492292 |

An Unexpected Compiler Moment

While researching the opening exercise a while back, I came across an article about why we use zero as the starting point of arrays and loops in computer science. The accepted folklore is that zero-based arrays are mathematically more elegant, or that they reduce execution time. Mike Hoye went on an archeological dig and found out that... (Emphasis mine.)

... the reason we started using zero-indexed arrays was because it shaved a couple of processor cycles off of a program's compilation time. Not execution time; compile time.

How could that be? When compiling BCPL on an IBM 7094 running CTSS...

... none of the offset-calculations we're supposedly economizing are calculated at execution time. All that work is done ahead of time by the compiler.

Why does that matter to us now? BCPL is a language from the late 1960s that was intended to be used to write compilers for other languages. It begat B, which Thompson and Ritchie used as their starting point when they created their new language: C.

Hoye's article is a fascinating read. Eugene sez: Check it out.

Where Are We?

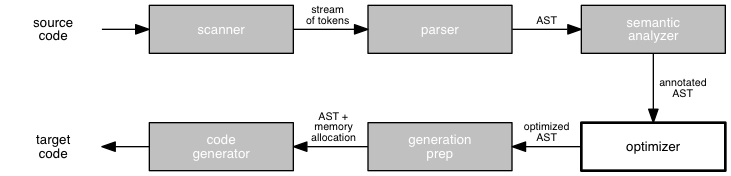

We are wrapping up our study of how to build a compiler by considering one last stage in the process: optimization.

Last session, we briefly considered some of the key ideas in the area of code optimization. An optimization must preserve the meaning of the input program, it should improve some measurable feature of the resulting program, and it should be cost-effective. Profiling and static analysis are two common ways to identify parts of the code that would benefit from optimization.

Common program transformations for optimization include elimination of subexpressions, copy propagation, elimination of dead code, and the folding of constants directly into the code. Code elements that commonly benefit from optimization include loops, function calls, and address calculations.

In this session, let's consider three common optimizations in some detail:

- unrolling

whileloops, - inlining function calls, and

- compiling tail calls, especially recursive calls, differently.

Optimizing while Loops

Last time, we studied how a compiler can "unroll" a

for loop by doing the computation of multiple

passes through the original loop in a single pass of the

optimized loop, as illustrated in

the example earlier in the session.

A while loop seems to present a bigger challenge

for an optimizer, because the compiler usually can't determine

how many times it will execute before terminating. But we can

use similar ideas about branching to improve the generated

code.

The bottom of a while loop is effectively an

unconditional jump to the top of the loop. We might convert

this statement:

while comparison do

statement

... into this:

top: while comparison do

begin

statement

if not comparison then goto next

statement

if not comparison then goto next

statement

end

next: ...

... and eliminate 2/3 of the unconditional jumps. The cost is, of course, a longer program and thus a larger executable.

But we can do even better! Recall that the three-address code

for a while loop looks something like this:

top: if not comparison goto next

statement

goto top

next: ...

We can convert the while loop into an

if statement wrapped around a

repeat-until loop:

if not comparison then goto next

top: statement

if comparison then goto top

next: ...

The resulting code has no unconditional jumps at all!

Like many topics in compiler writing, unrolling loops and otherwise optimizing them has more depth and breadth than we can do justice to in a single course, let alone a single week. We can only get a glimpse of what is possible. Even so, we can use even a simple idea like unrolling to improve the run-time efficiency of the code our compiler generates.

Inlining Function Calls

Introduction

Now let's look at a way to improve the efficiency of target code for function calls. This is especially valuable in a language such as Klein where function calls play such a central role in solving most problems.

There is a long of history of compiler writers optimizing function calls to improve the speed of executable code. One common technique is inline expansion of the function call in languages such as C++. Consider this C++ snippet:

int sum_of_squares(int x, int y)

{

return x*x + y*y;

}

...

result = sum_of_squares(location, 2) + 2;

The sum_of_squares function may add value to

the program in many ways, but it slows down execution of

the program. By adding the inline keyword

to the function definition:

inline int sum_of_squares(int x, int y)

{

return x*x + y*y;

}

... the programmer instructs the compiler to generate target code as if the function body were used instead of the function call:

result = (location*location + 2*2) + 2;

This technique is particularly useful for accessor methods in object-oriented programs. Programmers write these methods in order to make the code easier to maintain and modify (which are programming-time concerns), not more efficient (which is a run-time concern). The compiler can inline the calls and leave programmers with the best of both worlds.

We see a similar trade-off with named constants. We create named constants so that readers know the meaning of a value when it appears in the program. This makes it easier to maintain and modify the code. But at run-time, each reference to a named constant requires a memory look-up, which slows down the program.

A compiler can replace each reference to the constant with its value, improving the run-time speed of the code without hurting its readability. This optimization is called constant propagation.

The mechanism for inlining functions resembles the evaluation model in functional programming. A language interpreter evaluates expressions by repeatedly substituting computed values into compound expressions. Functional programmers often use this technique themselves in the form of program derivation as a refactoring technique.

An Example of Inlining in Klein

Inline expansion can be of great benefit in a language such as Klein, which does not have sequences or assignment statements. As a result, function calls are the only way a Klein programmer can name a value or prevent an expression from being evaluated multiple times. Yet stack space is precious, and these calls limit the size of the computations our programs can do.

Expanding a function call inline can balance these forces, but doing so requires more than just textually plugging in values as we did in the C++ example we just looked at.

Consider these two functions from generate-excellent.kln, a program that generates excellent numbers:

function aLoop1(a : integer,

n : integer,

upper : integer,

det : integer) : boolean

aLoop2(a, n, upper, det, SQRT(det))

function aLoop2(a : integer,

n : integer,

upper : integer,

det : integer,

root : integer) : boolean

aLoop3(a, n, upper, det, root, a * EXP(10, n) + ((root + 1) / 2))

I wrote these loops to simulate a sequence of assignment

statements inside a loop that looks for candidate

a's and b's. In Klein,

SQRT is expensive: it is a call to a recursive

function, not a built-in operator. I don't want to compute

the same value twice, so I compute it once and pass it to a

function that uses it to compute another value.

An optimizer might inline the call to aLoop2.

It would first compute the value of all the arguments that

aLoop1 passes to aLoop2, including

the creation of a new temporary variable:

t1 := SQRT(det)

and associate it with the formal parameter root.

aLoop2(a, n, upper, det, t1)

It could then replace the call to aLoop2 with a

call to aLoop3. This requires computing the

value of all the arguments that aLoop2 passes

to aLoop3, including the creation of a second

temporary variable:

t2 := a * EXP(10, n) + ((root + 1) / 2)

Now it is ready to substitute the call to aLoop3

in place of the call to aLoop2, leaving:

{ code for function aLoop1 }

t1 := SQRT(det)

t2 := a * EXP(10, n) + ((t1 + 1) / 2)

// code to call aLoop3(a, n, upper, det, t1, t2)

This sort of transformation works best on three-address code, which has the ability to sequence statements and use new temporary variables. But it could also be performed on the program's abstract syntax tree.

Other Loop Optimizations

The gcc compiler that comes with most Unix OSes can optimize function calls in many ways. As noted above, it can inline function calls, but it can do a lot more. Here are two examples:

- If the compiler sees a call to a function that passes a constant as one of the arguments, it will clone the function. The second copy hard-codes the constant value in the function body. When the clone is called, the compiler passes one fewer argument. We end up with larger executables that are faster and use less space at run-time.

- If the compiler sees that a function that does not use a register, then it does not save them in the stack frame. This results in faster programs and smaller run-time stacks.

For more about these function call optimizations and a slew of others, check out Interprocedural Optimization in GCC.

Optimizing Tail Calls

Introduction

Another way to optimize function calls is to improve the behavior of the calls on the run-time stack. This issue arises occasionally in public technical debate, as it did in 2009 when Guido van Rossum announced that Python would continue not to optimize for recursion and others explained why it might be worth the effort. Let's consider the issue in the context of Klein.

In our study of how programs typically work at run-time, we learned that...

-

A function call creates a new activation record for the

function on the call stack.

This record, also called a 'stack frame', contains the values of the arguments to the function, the state of the machine's registers at the time of the call, and space for any local variables. These local objects are the bindings created while executing the function, including any temporary objects not explicitly mentioned in the program. -

When the function returns, its activation record is

popped from the stack.

Before that happens, though, its return value is copied to the correct location in the caller, and the state of the machine's registers is restored. In practice, of course, nothing is really "popped". The top and status pointers are set back to the previous frames, and the function's return value is still accessible in the first slot just past the activation record on top of the stack.

The existence of a stack frame makes it possible to implement

recursive function calls, because now the compiler can create

a copy of the local variables, including arguments, for each

activation of the function. Thus, in this Klein program,

each invocation of this factorial function:

function factorial(n: integer): integer

if (n < 2)

then 1

else n * factorial(n-1)

... will have its own stack frame, with its own copy of the

formal parameter n. Written in this form, the

separate copies of n are essential, because they

are different and used upon return from the function.

Tail Recursion

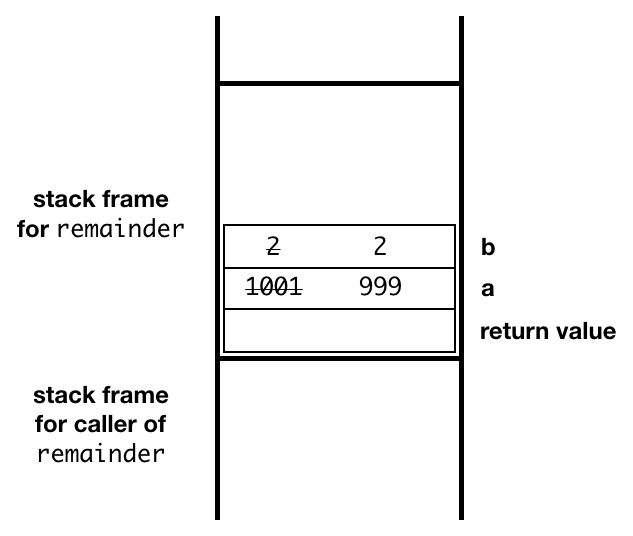

But some functions have a peculiar shape. Consider this function, from euclid.kln, which implements Euclid's algorithm:

function remainder(a: integer, b: integer): integer

if a < b

then a

else remainder(a-b, b)

Unlike factorial, which stores the result of the

recursive call in a temporary object for use in computing

its answer, remainder simply returns the result

of the recursive call as its own answer. There is no need

for temporary storage, and no further computation to do.

Think about what happens at run-time, when a call to

remainder(10001,2) reaches its base case.

1 will be returned as the answer from a call to

remainder(1,2) to an invocation of

remainder(3,2), which will immediately return 1

as the answer to an invocation of remainder(5,2),

which will immediately return 1 as the answer to an

invocation of remainder(7,2), ... and so on

— for 5000 stack frames, with no new computation

done.

This is an example of tail recursion, in which the recursive function call is the last statement executed by the function. With a tail-recursive function, the extra stack frames add no value. This is the insight we need to optimize:

We can reuse the original stack frame for all of the calls!

Instead of creating a new activation record, the new arguments

can be written into the argument slots of the existing record,

and the program can jump back to the top of the procedure.

Conceptually, we can think of remainder as doing

this:

function remainder(a: integer, b: integer): integer

top:

if a < b then

a

else

begin

a := a - b;

b := b;

goto top

The compiled code can write directly into the corresponding slots of the current stack frame.

Klein doesn't have assignment statements and gotos, but our compiler's three-address code does, and assembly language supports both with move and jump operations.

Suppose that our code generator has converted the Klein AST into a 3AC program of this form:

L1: IF a >= b THEN GOTO L2 T1 := a GOTO L3 L2: T2 := a - b PARAM T2 PARAM b T1 := CALL remainder 2 L3: RETURN T1

Optimizing the call away by turning into a loop is as simple as this:

L1: IF a >= b THEN GOTO L2 T1 := a GOTO L3 L2: T2 := a - b a = T2 # PARAM T1 b = b # PARAM b GOTO L1 # T1 := CALL remainder 2 L3: RETURN T1

We can prove that this change to the code does not change its

value, only how the value is computed. If Klein included a

goto statement, we can imagine programmers

making this kind of change to their own code, in an effort

to make it more efficient — but only if they knew that

the compiler couldn't do it for them!

This optimization is sometimes called eliminating tail recursion. It can be applied in cases where the recursive call is in the tail position of the function, that is, the value of the recursive call is the value of the calling function. A code generator, or a separate semantic analyzer running before code generation, can recognize tail-recursive calls without much effort and generate more space-efficient code.

Can you imagine how useful this would be in a Klein compiler? Take a look at some of the programs in the Klein collection. How many include tail-recursive functions?

Looking Ahead to Module 7

Module 7, the final stage of the project, goes live tomorrow. It will include three main tasks. The first two involve putting your project into a final professional form. The third is an improvement to the system.

- Make sure your system meets all functional requirements: fix any remaining bugs, catch any remaining errors, etc.

-

Make sure your project directory presents a professional

compiler for Klein programmers to use: a

READMEsuitable for new users,doc/files with clear names, etc. - Add one improvement to the system: an optimization, a better component for one of the existing modules, etc.