Session 27

Introduction to Optimization

Where Are We?

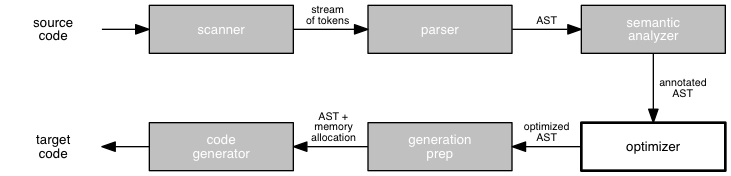

For the last few weeks, we have been talking about the synthesis phase of a compiler, which converts a semantically-valid abstract syntax tree into an equivalent program in the target language. This involves building a run-time system to support the execution of a program in target code, perhaps translating the AST into an intermediate representation such as three-address code along the way, and generating code in the target language.

Most recently, we learned a basic algorithm for generating target code, including register selection and backpatching jump targets. Last time, we learned about a way to improve register selection using next use information. Then we looked at code for a complete code generator, Louden's code generator for "Tiny C".

In this session, we move on to the final topic of the course, optimization. But first, let's take a quick look at a practical matter: giving boolean command-line arguments to a TM program.

Klein Command Line Arguments and TM

Now that you are writing

a code generator

for the entire Klein language, you face the practical matter

of testing boolean arguments to main(). The

challenge is that, while Klein supports both integer and

boolean values, TM supports only integers.

I wrote this TM program that echoes its argument:

0: LD 0,1(0) 1: OUT 0,0,0 2: HALT 0,0,0

How does it behave with non-integer arguments?

$ tm-cli-go echo.tm 2 OUT instruction prints: 2 $ tm-cli-go echo.tm s (null) is not a valid command line argument true, false or integer values are valid arguments $ tm-cli-go echo.tm true OUT instruction prints: 1 $ tm-cli-go echo.tm false OUT instruction prints: 0

So: We can use Klein's boolean literals true

and false as command-line arguments to TM.

Thanks again to Mike Volz, CS 4550 Class of 2007, for this

extension to TM.

On to Optimization

This semester, we have learned basic techniques for building a compiler that converts a semantically-valid program written in a source language into an abstract syntax tree, and then into an equivalent program in a target language. While a source program is usually written best when it communicates well with human readers, an executable program is usually written best when it meets the needs of the target machine, is small, and runs fast. How can we produce such a target program?

In this session, we consider briefly some of the key ideas in the area of code optimization. Optimization can happen at any stage of a compilation:

- optimizing the AST before generating IR

- optimizing the IR before generating target code

- optimizing target code directly

You may be surprised at how easily we can optimize your Klein-to-TM compiler using these ideas. Even if you do not have time to implement them in your compiler, you can appreciate the ideas and the process.

Optimizing Code

As we have learned TM assembly language and code generation this semester, we've often seen that the TM programs we wrote by hand were shorter and more efficient than the TM programs produced by our code generation techniques. Why is that?

The main reason is that our code generation techniques focus on a single IR statement or a single AST node at a time, while we could keep the entire program in our head at one time and reason about it as a whole.

Ideally, we would like for our compilers to generate target code that is as good as or better than the code we could write by hand. A good optimization stage can help our compiler do better.

What Is Optimization?

The term optimization is a misnomer, really, because showing that a piece of code is optimal is undecidable. More accurately, an optimizer simply improves the code in some objective way.

Actually, we have already improved the quality of target code

in an objective way several times during the course. For

example, in Session 25, we saw that

implementing a better getregister() utility

and using a memory map could help

the basic code generation algorithm

produce more efficient code. However, these kinds of

improvement do not change the content of the program itself;

they change the internal mechanisms of the compiler. So we

would not call them "optimizations".

That said, there is no bright line between the techniques we call optimizations and the techniques we think of as simply writing a better compiler. Perhaps when a technique becomes so standard that "everyone does it", it is no longer considered an optimization.

Some optimizations are independent of the target machine, as they manipulate the computation being done by the program in some way. Others take advantage of the target machine's features to generate code that runs more efficiently on that machine only. Many machine-independent transformations can be done on the intermediate representation, prior to code generation. Machine-dependent transformations are best accomplished when generating target code.

Whatever the nature of an optimization:

- It must preserve the meaning of the input program. The modified program should behave in essentially the same way as the original program.

- It should improve the speed, the size, or some other feature of the resulting program.

- It should be cost-effective. That is, the total value gained from the improvement to the code should exceed the total cost of implementing the optimizer and executing it on programs.

Optimizing Through Profiling

A common approach to designing an optimizer is to identify a set of typical target programs, find the most frequently executed code structures in them, and focus efforts to improve the compiler's performance on these common structures. This echoes the conventional wisdom of the 80/20 Rule, which says that 80% of some cost follows from 20% of the resources.

To implement such an approach, we might use a profiler to execute a program on an accepted suite of data and identify the hot spots in the program.

Finding or creating a widely accepted suite of input programs to use with a compiler can be difficult, though it has been done for many languages, including C, Tex, and Scheme. We have built a suite of Klein programs that can serve as a benchmark for compiler performance.

Optimizing Through Analysis

Another common approach to implementing an optimizer is to:

- Do static analysis of the code generated by the compiler, focusing on the flow of data or control through the program. Such an analysis builds a graph that 'chunks' the intermediate representation into blocks defined by transfers of control or changes in data objects.

- Apply one or more transformations to the code, motivated by the features of these chunks.

Common Optimizations

Common program transformations for optimization include eliminating subexpressions, copy propagation, eliminating dead code, and folding of constants directly into the code. Code elements that commonly benefit from optimization include loops, function calls, and address calculations.

In our time together, let's consider three common optimizations in some detail:

- unrolling loops,

- inlining function calls, and

- compiling tail calls, especially recursive calls, differently.

We'll look at loops today and functions next time.

Optimizing Loops

Loops are a common target for optimization. A few simple transformations to a loop can produce code that runs much faster on large inputs. The cost of such transformations is that they usually produce larger target programs. One example of this is unrolling a loop.

Consider this counted loop in C:

for (i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

s = s + i*i;

printf("%d\n", i*i);

}

The loop increments the counter i 1000000 times,

branches back to the top of the loop 1000000 times, and checks

the exit condition i < 1000000 1000001 times.

All of these operations are overhead to the actual work

being done: the computing and printing of a running sum.

We can reduce the overhead if we write a longer program, "unrolling" some of the loop iterations into explicit statements:

for (i = 0; i < n/5; i+=5) {

s = s + i*i;

printf("%d\n", i*i);

s = s + (i+1)*(i+1);

printf("%d\n", (i+1)*(i+1));

s = s + (i+2)*(i+2);

printf("%d\n", (i+2)*(i+2));

s = s + (i+3)*(i+3);

printf("%d\n", (i+3)*(i+3));

s = s + (i+4)*(i+4);

printf("%d\n", (i+4)*(i+4));

}

The unrolled loop increments the counter i only

200000 times, branches back to the top of the loop only 200000

times, and checks the exit condition only 200001 times.

Not surprisingly, the unrolled loop runs approximately 80% faster. Here are two typical runs on my MacBook Pro:

> time for-loop > /dev/null real 0m0.235s user 0m0.082s sys 0m0.009s > time for-loop-unrolled > /dev/null real 0m0.170s user 0m0.027s sys 0m0.005s

Redirecting standard output to /dev/null saves us

from having to see all of the output. It also saves the time

of writing all of the output to the screen. It does not affect

the magnitude of the speed-up.

Ordinarily, the tradeoff for this optimization is an increase in the size of the generated code. But check this out:

-rwxr-xr-x 1 wallingf staff 33432 Dec 2 11:22 for-loop -rwxr-xr-x 1 wallingf staff 33440 Dec 2 11:22 for-loop-unrolled

No change! Can you imagine why?

What happens, though, if we unroll the for loop

all the way?

Try it! If you do, try gcc -w to suppress

warnings related to

On my machine, the executable runs slower than the original loop, and the compiled code is over 4000 times larger. Can you imagine why the code runs slower?

Modern pipelining processors make the benefits of unrolling a loop harder to pin down. gcc has flags to control its loop-unrolling behavior and many other optimizations, but its default behavior is often what most programmers want most of the time.

The two smaller for-loop programs are in

today's zip file,

along with a Python program that generates the statements of

the completely unrolled loop. (I did not type that one by

hand!) If you want that program, too, download it separately:

for-loop-unrolled-all.c

.

It's big enough — nearly 58 MB — that I won't

saddle you with it unless you want it.

Wrap Up

Klein doesn't have a loop construct, so this optimization can't help us. Next time, we turn our attention to Klein's most important feature, the function call, and learn how we might optimize the code our compiler generates — which, ironically, might involve generating a loop!