Session 24

From Intermediate Representation to Target Code

Opening Exercise

Last time, we looked at a method for generating three-address code using templates for each kind of node in the language's abstract syntax. Here is a list of four common templates: two for compound expressions (from last time) and two for the atomic expressions identifier and literal.

This generation method walks the AST, making recursive calls for subexpressions until it reaches the leaves.

Now you try it...

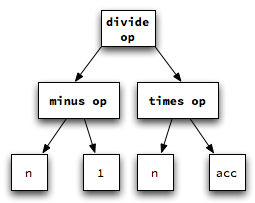

Generate three-address code for the AST at the right.

This tree corresponds to the Klein expression

(n-1) / (n*acc).

The templates for the binary operators - and

/ are of the same form as the template for

+ and *. That will be

true for all binary operators.

After you have written your 3AC program, take a look at my solution. How do they compare?

Like many of the techniques we have learned in the course, this technique is sturdy, reliable, and verbose. With a little knowledge, a code generator can make more efficient choices and generate better code.

Our templates thus far for generating three-address code handle

several basic kind of AST nodes. We have not yet considered

two other kinds of expression present in Klein and most other

programming languages: control structures like if

and function calls. Let's look at templates for these now.

Three-Address Code for Control Structures

Most source languages have high-level control structures such

as if..then..else.. and for..in...

Three-address code represents such statements using code labels

and jumps, much like assembly language.

Loops

Consider a simple while statement:

S → while E do S1

First of all, we need to make a decision about the semantics of boolean values in our little language. What values of E count as true, and which count as false? For simplicity, let's define 0 as false and everything else as true.

Second, we need to create a new procedure in our code generator: a procedure that produces unique labels for use in the generated code. Unlike the case of temporary variables, we cannot reuse labels multiple times. They all exist in the same namespace, so they must be unique.

Let's assume the presence of a procedure named

makeNewLabel() that generates the sequence

of unique labels L1,

L2, L3, ....

Now we are ready to generate three-address code for the

while statement. This translation resembles

the one that you make when implementing a loop in assembly

language.

We need to generate code bodies for the expression E

and the statement S1, then use jumps to

ensure that the 3AC code has the same semantics as the

while statement. Here is a picture of what the

generated code might look like in memory:

So, we need to generate two labels and make recursive calls

to generate code for E and S1. The semantic

action for the while statement would look

something like this:

S → while E do S1

------------------

L1 = makeNewLabel()

L2 = makeNewLabel()

S.code := emitCode( L1, ": " )

[ E.code ]

emitCode( "if ", E.place, " = 0 goto ", L2 )

[ S1.code ]

emitCode( "goto ", L1 )

emitCode( L2, ": " )

Selection

Consider this form of if:

S → if E1 = E2 then S1

Not surprisingly, this turns out to be quite similar to the

semantic action for the while statement. An

if statement is a degenerate loop, in which

there is no branch back to the test. Here is a picture of

what the generated code might look like in memory:

The semantic action itself might look something like this:

S → if E1 = E2 then S1

-----------------------

L3 = makeNewLabel()

L4 = makeNewLabel()

S.code := [ E1.code ]

[ E2.code ]

emitCode( "if ", E1.place, " = ", E2.place, " goto ", L3 )

emitCode( "goto ", L4 )

emitCode( L3, ": " )

[ S1.code ]

emitCode( L4, ": " )

-

How would inverting the test condition to

if E1.place != E2.placechange the code to generate? -

How would adding an

elseclause change our semantic action to generate code?

Closing

Generating efficient three-address code for boolean

expressions creates some interesting challenges. For

example, how can we produce three-code code for

and and or expressions that "short

circuits" evaluation as soon as possible? What is the key

problem to be solved?

Three-Address Code for Function Calls

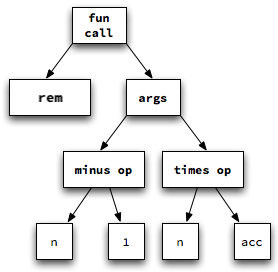

As simple as this technique for generating 3AC is, it scales quite nicely to handle larger grammars and more complex expressions. Consider, for example, this Klein expression:

rem(n-1, n*acc)

What do we need to generate 3AC for this AST? We need a

template for function calls like the ones for if.

We could define one something like this:

E → F(E1, ...)

------------

E.place := makeNewTemp()

E.code := [ E1.code ]

... code areas for other Ei

emitCode( "PARAM ", E1.place )

... PARAM entries for other Ei

emitCode( E.place, " = CALL ", F.place, " ", count )

This template computes the code for each of the arguments passed to the function and then emits code to pass the arguments and call the function.

Here is the three-address code produced for the AST :

t1 := 1 t2 := n - t1 t3 := n * acc PARAM t2 PARAM t3 t4 := CALL rem 2

This code use more temporary variables than necessary. We can certainly generate more frugal three-address code, or have the code generator optimize the 3AC code it generates with local improvements.

What do we know that would allow us to generate more efficient 3AC?

-

After we compute

t2, we are done witht1. We can reuset1to store the result of the operation. -

After we put

t1andt2on the run-time stack, we are done with both of them. We can re-use one of them in place oft4.

The idea here is of the next use for a value. If the code has no next use for the value stored in a variable, then the code generator can reuse the variable in which it is stored.

A 3AC generator that records next-use information might create a more efficient solution for the function call AST:

t1 := 1 t1 := n - t1 t2 := n * acc PARAM t2 PARAM t1 t1 := CALL rem 2

Is there any other information a 3AC generator could keep track of in order to be more efficient?

We will look at these ideas a bit more next week, when we consider the related task of selecting registers for the target code we generate. Better information enables a code generator to produce better code.

On to Target Code

... finally! We are ready to consider the task of generating code for the target machine.

After the compiler translates the AST of a source program into an intermediate representation such as three-address code, it must then translate the 3AC into target code. A code generator can do this in a couple of different ways:

- generate target code in real time as it generates 3AC

- make a second pass over the 3AC that translates it into target code

Whether our compiler translates the AST into an intermediate program and then into target code, translates the AST directly into target code, or even generates target code immediately during the parsing phase, it will typically follow a common pattern:

generateCode( AST binary_tree ) // or 3AC statement

{

generate code to prepare for code of left subtree

generateCode( binary_tree.leftChild() );

generate code to prepare for code of right subtree

generateCode( binary_tree.rightChild() );

generate code to implement tree's behavior

}

This repeats and generalizes an idea that we have seen several times since we began looking at how to write three-address code. It is a post-order traversal of the tree, or of each instruction in a sequence. This traversal includes steps for generating code that must be inserted for the sub-expressions. The preparation code generally depends on the kind of tree being processed.

The best sort of intermediate representation as input to a code generator has data objects that map directly onto the primitives of the target machine. This includes the insertion of type conversion operators. (This is one of the things a semantic checker can do to add value to the AST.)

The output of the generator can be either absolute or relative.

- Absolute code has all of its addresses already computed and placed in the code. A program in this form can be loaded anywhere and executed immediately. The downside is that it requires compiling the entire program at the same time, which limits the flexibility available to programmers who use the compiler.

- Relative code uses addresses that are computed as offsets, which must be resolved at the time the program is loaded to execute. A program in this form offers the flexibility of separate compilation but requires the cost of linking modules and loading each time the program is run.

Klein does not have modules that can be compiled separately, and Klein programs are otherwise simple enough to compile all at once. This makes it possible for your code generator to produce absolute addresses.

A code generator that produces assembly language as the target language allows the compiler to rely on the assembler facilities of the target machine, which are often considerable. In contrast, a code generator that produces machine language directly must do all of the work that an assembler might already do — but perhaps can do it more efficiently.

We will see one of TM's facilities that helps us soon.

For your project, you are producing the assembly language of a simple, special-purpose machine for which we have a simulator. We rely on Louden's TM assembly language to provide several machine-specific primitives, including I/O primitives.

Code generation includes two important sub-tasks: target instruction selection and register allocation.

- Selecting target instructions is the essential element of code generation. The size and richness of the target machine's instruction set drives the selection process. The uniformity with which it treats data and control determines the complexity of the selection process.

- How well a compiler uses registers can have a large effect on the efficiency of the target program. Instructions that work with data in registers are typically shorter and much faster than ones that work only with data in memory. Machines that provide only a small number of registers generally require the code generator to produce more instructions.

Today, let's consider the selection of target instructions, and next time we will consider register allocation.

Techniques for Selecting Target Instructions

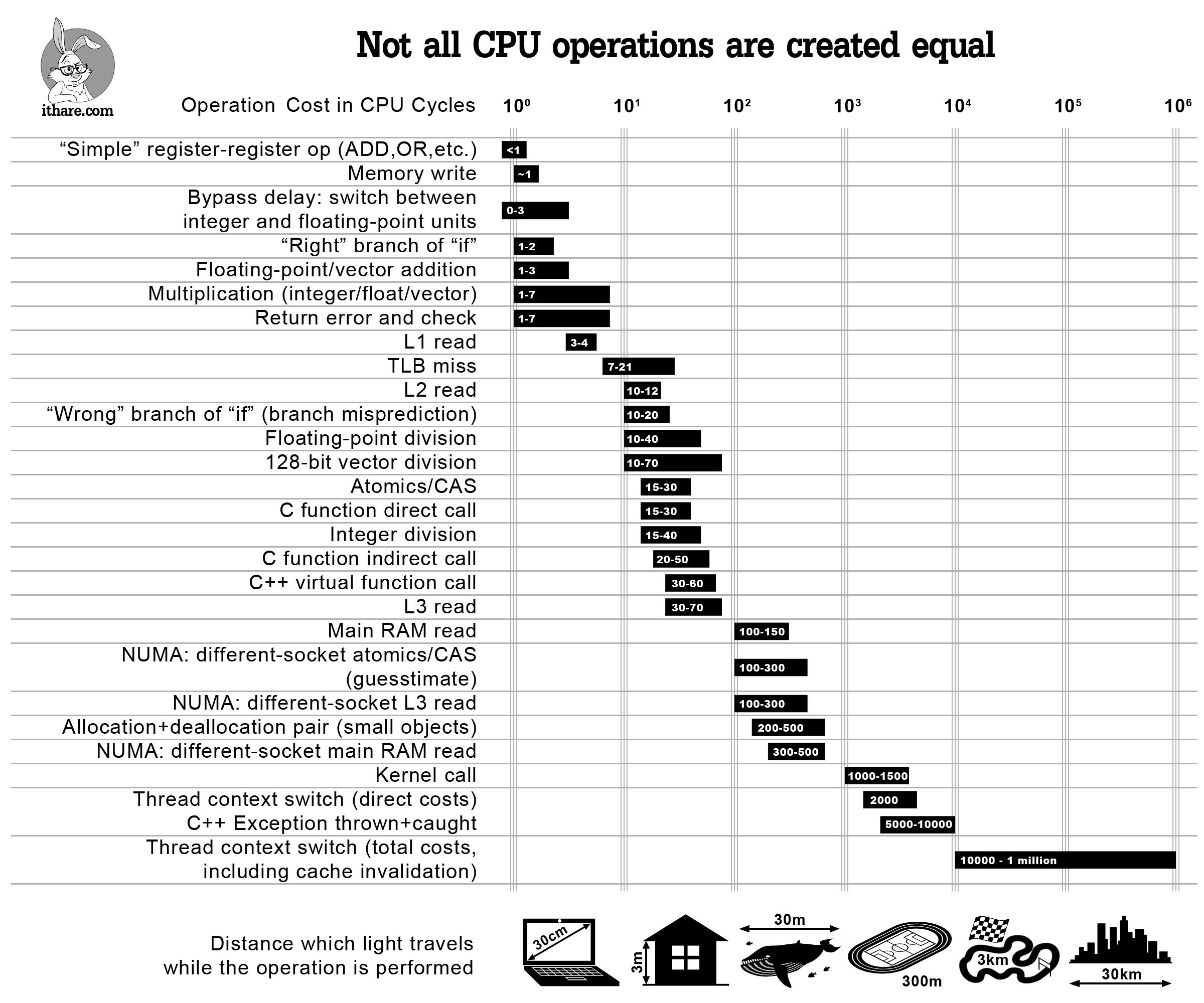

Selecting the best target instructions for a given expression can be a difficult task, but it can be worth the effort. Different classes of instruction have widely varying costs in terms of CPU cycles, as shown in this infographic:

To generate efficient target code, the compiler must take into account the speed of each target instruction and implement the idioms of the target machine. Unfortunately, accurate data about instruction speed is often hard to come by.

One of the oldest techniques for generating target code is static simulation, in which the code generator interprets the AST or the intermediate representation, generating target code at suitable points. Implementing this technique is quite similar to implementing any language interpreter, using a style similar to what you learn in a Programming Languages course. This approach works well when the constructs of the IR do not map very well onto the constructs of the target language, but it is not the most efficient way to generate target code.

Another technique is known as macro expansion, in which an expression is replaced with a lower-level representation of the same expression.

Some programming languages expose a macro expansion facility to programmers. C provides the simplest form of macro expansion possible, expanding text into text. More sophisticated macro facility, such as those in Rust or Racket, support more complex code generation. One can build an entire compiler as a long sequence of macro expansion-like code transformations.

For your project, I recommend that you use a simple form of macro expansion known as code skeletons, or templates. A code skeleton provides a simple way to generate a set of target instructions all at once. In this approach, the generator associates a template with each instruction in the intermediate language. Code skeletons do not generate the most efficient code, but the technique is simple to understand and implement.

Consider this generic three-address statement:

a := b + c. A compiler can expand this statement

into target code using the following TM assembly language

template:

LDA r1, a LD r2, b LD r3, c ADD r2, r2, r3 ST r2, 0(r1)

The registers ri are selected from the

pool of available registers. To complete the template, the

code generator replaces the identifiers a,

b, and c with the addresses of the

corresponding objects in memory, using expressions of the form

d(s). The objects may be in a static location,

in an activation record on the call stack, or somewhere else

computable by the code generator.

In this approach, each kind of 3AC statement will have its own template. The code generator expands each 3AC statement using its template and produces target code.

The first step for you in implementing your code generator is to define a TM code template for each kind of 3AC statement in your IR, or for each kind of node in your AST.

You can probably see how this would lead to inefficient code. Target code for each 3AC statement is generated independently of the statements around it, which misses out on opportunities to take advantage of relationships among those statements.

For example, if the next statement in our 3AC program is

d := a * f, it will immediately load

a back into a register:

LDA r1, a LD r2, b LD r3, c ADD r2, r2, r3 ST r2, 0(r1) ; store a LDA r1, d LD r2, a ; re-load a LD r3, f ADD r2, r2, r3 ST r2, 0(r1)

A generator of more efficient code might eliminate the

ST instruction from the + template

and the first LD instruction from the

* template.

An optimizer can also improve the target code generated at the boundary between two templates later.