Session 11

Toward Abstract Syntax in the Parser

Success: My First New Klein Program This Semester

Last time, I mentioned an idea for a new Klein program to convert any fraction fraction m/n into an Egyptian fraction of the form 1/k1 + 1/k2 + ....

I love to write code, which means that fun programming ideas

rarely sit untried for long. Here is

egyptian-fractions.kln.

It demonstrates a couple of Klein design patterns, including the

use of a "print-and-continue" function that works around Klein's

limitation of allowing print expressions only at the top of

functions.

As I said last time: Please write a Klein compiler so that I can run my programs!

Opening Exercise

In Session 2, we studied a compiler for Fizzbuzz, a simple language. That compiler came with a recursive-descent parser. We now know how to build a fast, efficient, table-driven parser for Fizzbuzz. It's not very big... Let's build one.

program is the

start symbol:

program ::= range assignments

range ::= number ELLIPSIS number

assignments ::= assignment assignments

| ε

assignment ::= word EQUALS number

word ::= WORD

number ::= NUMBER

Step 2. Use the FIRST and FOLLOW sets to build a parsing table for the grammar. The main step in the table construction algorithm is:

For each productionA := α...

- For each terminal a in FIRST(α), add

A := αto table entry M[A, a].- If ε is in FIRST(α), add

A := αto table entry M[A, b] for each terminal b in FOLLOW(A).

Check out my answers if you have any questions. Fizzbuzz is a simple language, so its parsing table is pretty simple, too.

Implementing a Table-Driven Parser

For the last few sessions, we have been learning how to construct a table-driven parser. This style of parser consists of a language-neutral algorithm operating over a parsing table that encodes the grammar of a particular language. During execution, the parser uses a stack of grammar symbols yet to be matched.

Last time, we closed with a discussion of some of the issues we face when implementing a table-driven parser in code. This includes the table itself as well as grammar rules and the grammar symbols they contain.

To demonstrate one way to implement a table-driven parser, I used the answers from our opening exercise to write a new parser for Fizzbuzz. Let's take a look at:

- the code for representing non-terminals

- the code for the parsing rules and the parsing table

- operators for manipulating the parse stack

- the

parse()function itself

Here is

the new Fizzbuzz directory

[

zip file

]. The parser is in file

td_parser.py,

and the file

fizzbuzzf

drives the parser.

I try to be reasonably Pythonic + in style, to the point of using dead lists to represent parse rules. However, I did create stack operators that let me think in terms of the parse stack and not the underlying lists. With more time and a more OOP mood, I might add more object thinking to my blend. Experience has taught me to be skeptical of primitive obsession +.

For more on what "Pythonic" means, check out

this classic post

from the Python world.

"Primitive obsession" is a name for using a primitive data type

in your language instead of a creating domain-specific type or

value. For more on what "primitive obsession" means, check out

this old post of mine.

I strongly encourage your team to think through the issues and design a parser you understand well and are comfortable with. You will be spending a lot of time inside the parser code for the next few weeks, and you'll need to be able to maintain it for the rest of the project. Use my examples only as an inspiration.

The Demands on a Parser

The first job of a parser is to determine whether a program is

syntactically correct. This is a boolean decision: yes,

the program is legal

, or no, the program is not

legal

. The parsing techniques we've looked at so far do

this.

But in the context of a compiler, the parser must also produce information used by the rest of the program:

- The semantic analyzer needs to be able to verify various static features of the program, such as types of variables.

- An optimizer needs to be able to manipulate the program in ways that make it better along some dimension, such as execution time.

- The code generator needs to be able to produce equivalent code in the target language.

These phases of the compiler need to know the structure of the source program as well as the semantic values of the identifiers and literals it contains.

To support these tasks, the parser could produce a parse tree. A parse tree records the derivation done by the parser. Consider this expression from our simple grammar in Sessions 9 and 10:

x + y

The parse tree for this expression looks something like this:

Yikes! That is a lot of tree for not much expression. By

showing the full derivation, a parse tree records unnecessary

information, including non-terminals rewritten as other

non-terminals (such as when factor becomes

identifier), the marker non-terminals that

we added solely to make the grammar deterministic (such as

expression'), and even non-terminals that

disappear when rewritten as ε (such as both instances

of term').

Parse trees expose details of the concrete syntax of the language to compiler stages downstream, such as punctuation and terminators. The semantic analyzer and the code generator operate on the meaning of the program, not on its syntactic form, and leaking such details couples those stages of the compiler to information outside their concern. We would like to implement those stages independent of the language grammar.

Instead, we prefer to have the parser generate an abstract

syntax tree that records only the essential information

embodied in the program. A programmer looking at the

expression above might think,

That's an addition expression

. We could represent that

idea with this abstract syntax tree:

Or perhaps a programmer used to working at a higher level might

think, That's a binary expression with a

We might represent that idea with this abstract

syntax tree:

+

operator."

Either one is much better than the original parse tree. These trees record the information needed by the semantic analyzer, optimizer, and code generator to do their jobs — and no more.

There is one more thing we'd like our parser to be able to do. When it encounters an errors, we would like for it to provide messages that the programmer can use to find and fix the errors. If we want the parser to be able to handle errors in a graceful way and report them to the programmer, we need to add one more bit of information to our AST: the position of element in the original source file. This information can also be useful for other kinds of downstream processing, such as refactoring and unparsing.

The abstract syntax tree (AST) serves as the primary input to all later phases in the compiler.

Defining the Abstract Syntax of a Language

We experience the idea of abstract syntax every time we learn a new language and see new concrete syntax for a construct we already know from another language.

For example, in Intro to Computing you learn about

if statements in Python:

if condition: then-clause else: else-clause

There is another way to write if statements in

Python, too:

then-clause if condition else else-clause

Then, in Intermediate Computing, you learn that Java has an

if statement of this form:

if (condition) then-clause else else-clause

If you take Programming Languages, you will see Racket's version

of if:

(if condition then-clause else-clause)

The lucky among you may have heard me talk about the

if expression in Smalltalk:

condition ifTrue: then-clause ifFalse: else-clause

Finally, Klein has an if expression in the

tradition of Pascal and its offspring:

if condition then then-clause else else-clause

These statements and expressions use different keywords, different punctuation, and even some whitespace. But all contain three essential elements:

- a test condition

- a then-clause

- an else-clause

These are the components in the abstract syntax of

an if statement.

Consider Fizzbuzz. What are the essential kinds of expression in this language? What values does each contain? We can see what I as programmer thought by examining the nodes that can be created in the Fizzbuzz compiler's ASTs : a program node, a range node, and an assignment node.

(In a sad moment of laziness, I used a Python list for assignments, rather than creating an assignment-list node. Primitive obsession rears its ugly head.)

Consider again the simple expression grammar that we have been using as a running example. What are the essential kinds of expression in this language? What values does each contain?

Abstract syntax represents the essential kinds of expression in the language. For each kind of expression, it records the values that make any instance of the expression unique. The type of expression is defined in the kind of node used.

When we implement ASTs in a programming language, we may create interfaces or abstract superclasses that help us to unify ideas such as "an expression" for the purposes of static typing or code hygiene.

Now let's consider Klein. What are the essential kinds of expression in this language? What values does each contain?

Building Abstract Syntax in a Table-Driven Parser

What is the challenge in extending a parser to build and return an abstract syntax tree?

Recall our table-driven algorithm for top-down parsing. The parser acts on the basis of the next token in the input stream, t, and the symbol on top of the stack, A, until it reaches the end of the input stream, denoted by $.

This algorithm allows a parser to recognize a legal program and to signal an error when it encounters an illegal construction. But it does not construct the abstract syntax tree that is the desired output of a parser. At Step 3.2.1, when the parser expands a non-terminal according to a grammar, we could add a hook for taking some action associated with a newly-expanded rule, but... What kind of action would that be?

What we need is the ability to associate a command to construct a node for the abstract syntax with certain productions. For example, consider again our refactored expression grammar:

-

If we are successful at expanding a factor

into an identifier, the parser can create an

identifiernode for the program's AST. -

If we are successful at expanding an expression'

with a

+operator and a term, the parser can create anaddition-expnode for the program's AST.

We call a command like this, one that creates a node for the AST, a semantic action.

We saw an example of semantic actions in our Fizzbuzz compiler during Session 2. Whenever that program's ad hoc recursive descent parser reached the end of a state machine successfully, it built and returned an appropriate node for the AST. The semantic actions in this parser are the calls to the constructors. I inserted these actions at the point in the recursive descent where the parser has successfully expanded a non-terminal. Using Python's run-time stack hides the state of a growing AST behind the function calls.

For example, imagine that we were parsing the expression

A + B * 1 in Klein, Java, Python, or any

language with arithmetic operators. The AST would grow as

follows:

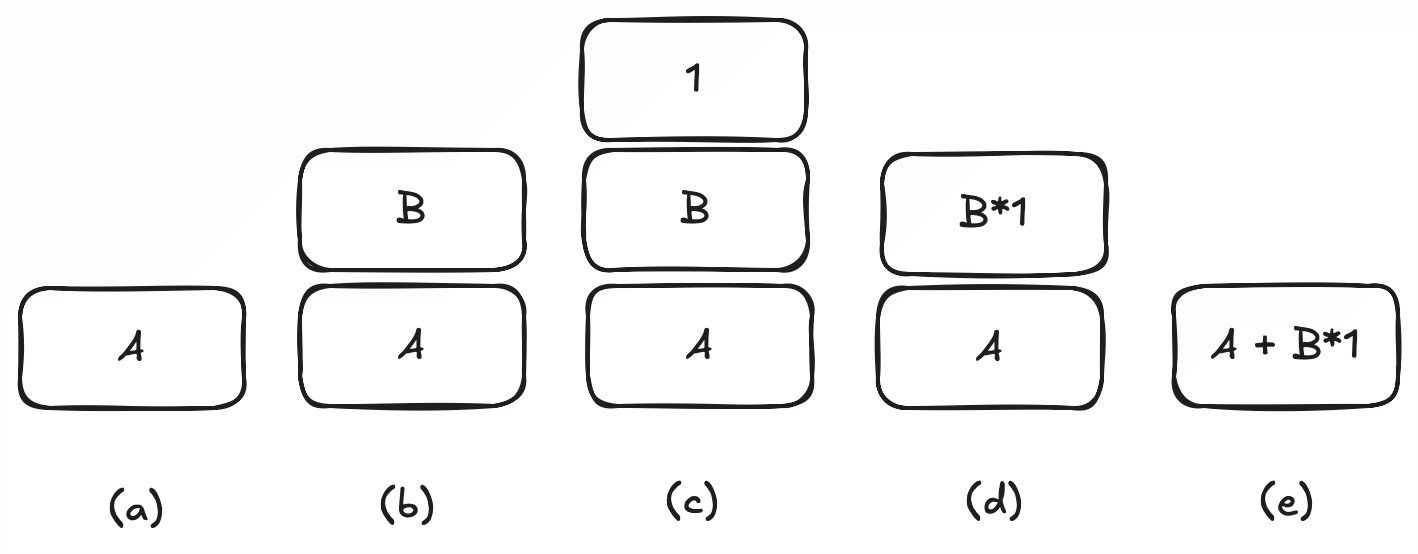

-

parseExpressiontries to parse the expression. -

(a)

parseValueproduces anIdentifierrecord forA. -

parseExpression'tries to continue and sees the plus operator. -

(b)

parseValueproduces anIdentifierrecord forB. -

parseExpression'tries to parse sees the times operator. -

(c)

parseValueproduces anIntegerValuerecord for1. -

(d)

parseExpression'produces anTimesExprecord forB * 1. -

(e)

parseExpressionproduces anPlusExprecord forA + B * 1.

Like recursive descent, a table-driven parser works top-down, too, so it performs a left derivation of its input stream. When the parser builds a node for the AST, it has to remember the result, because the node may be part of a higher-level expression that hasn't been encountered yet!

For example, a parser that is recognizing the expression

x + y will recognize the term x

before it even encounters the + token, which

will result in an AST node that contains the node for

x.

A recursive descent parser maintains this information on the call stack, along with the results of the procedure calls that create the node's subtrees. A table-driven parser will need a new data structure in which to store these partial results. We call this new stack the semantic stack. It holds pieces of the AST until such time as they are used to build a higher-level node in the tree.

Table-driven parsing introduces a new wrinkle. The parser expands non-terminals before their components are processed. By popping the expanded non-terminal from the stack, the parser loses record of the fact that the non-terminal ever existed — and thus of the need to produce an AST node for it. However we handle semantic actions, we need to iron this wrinkle out, too.

Next time, let's consider how to extend our parsing table with semantic actions and our parsing algorithm with a semantic stack. We'll iron out that wrinkle, too.