Session 8

Top-Down Parsing

Recap: Ambiguity in a Grammar

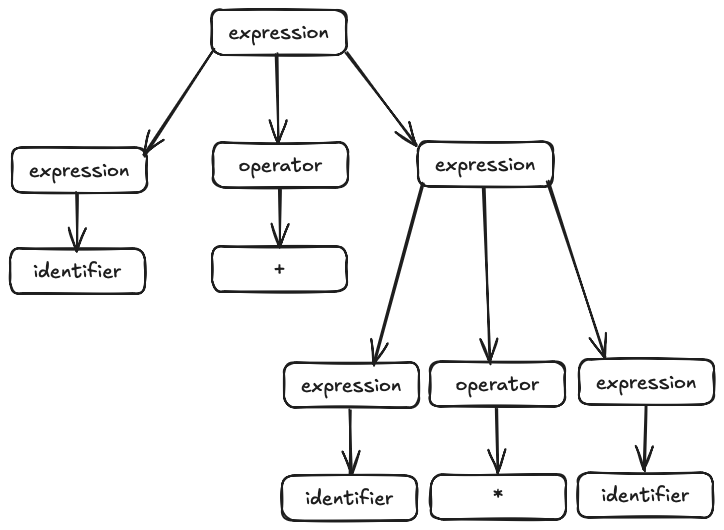

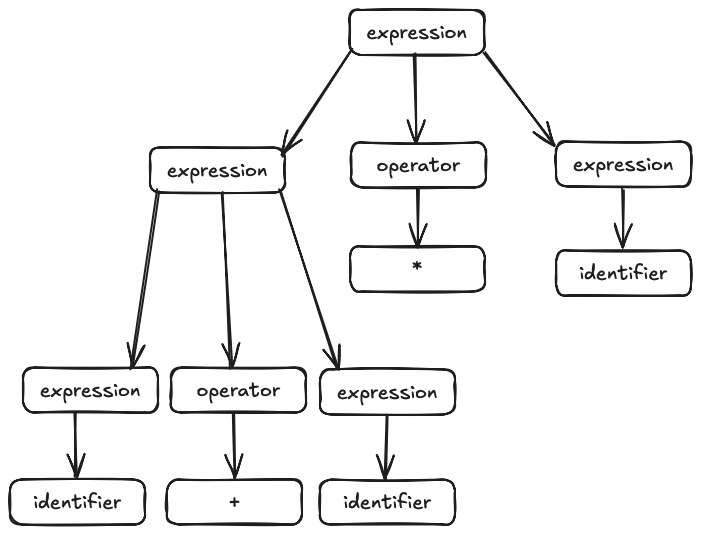

In our final example last session, the same sentence had two different but valid parse trees.

When this is possible, we say that the grammar is ambiguous. Committing to a leftmost or rightmost derivation does not avoid all of the ambiguities, because our second choice, of which substitution rule to use, creates another form of non-determinism.

Theoretically, this sort of ambiguity may not matter much. If all we need to do is answer the question, Is this sentence in the language?, then ambiguity is not a problem. If a sentence has two legal derivations, then it is certainly a member of the language.

Practically, though, it matters a lot. Different parse

trees give different meanings for the underlying program. In

our example above, the first tree binds the * more

tightly than the +; the second binds the

+ more tightly than the *. If we

intend for our language to follow the standard precedence rule,

then we want the first parse tree.

Unfortunately, the precedence rule isn't the reason that we arrived at the desired result. That was just an accident. Our parsers must use an approach that generates the correct abstract syntax tree for all programs.

We need to eliminate the ambiguity from the grammar.

Eliminating Ambiguity from a Grammar

Introduction

Often, we can eliminate ambiguity by refactoring the grammar: that is, by restructuring it in a way that does not change the set of strings it describes. We can use two common techniques to refactor a grammar in a way that eliminates ambiguity:

- eliminating left recursion

- left factoring

Eliminating left recursion

Allowing recursion in a grammar creates a practical problem for parsers. Consider this grammar:

A := Aa | b

This grammar is left-recursive because A occurs as the first symbol on the right hand side of a rule that defines A.

Why is that a problem for a parser? It has to decide which rule to use when it expands an A, based on the next token in the stream. If you think about these two rules for a minute, though, you will realize that all possible instances of A must begin with b; otherwise the recursion will never terminate. So b is the "lead" symbol for both rules.

When the parser sees a b and tries to decide which rule to apply, it faces the fact that both rules apply. Any algorithm that uses this grammar to recognize its language will be nondeterministic.

The solution to the problem is to rule out left recursion. This restriction turns out not to be much of a problem in practice, because we can always rewrite a rule that uses left recursion in a form that doesn't use it.

For example, in this case, we could simply use repetition:

A := ba*

In other cases, we can factor the common behavior into a separate rule and rewrite the original rules. Consider this subset of our arithmetic grammar from earlier:

expression := identifier

| expression operator expression

We can eliminate the left recursion by moving

identifier to the left of the rule for

expression and creating a second rule for the

"tail" of the expression:

expression := identifier expression-tail

expression-tail := operator expression

| ε

The new grammar generates the same set of sentences as the original two rules, without left recursion.

Actually, if these rules are part of a larger grammar, then the grammar may still be ambiguous. Something else must be true in order for the new rules to work. Can you figure out what that is? We will see the answer, and a way to detect the ambiguity, soon.

Left factoring

Another source of ambiguity is when two rules start with the

same token. Consider the common case of the optional

else clause:

statement := if expression

then statement

else statement

| if expression

then statement

This creates the same sort of problem for our parser as above. When it sees an if token next in the stream, it finds that both rules apply. The parser would have to look ahead at least four tokens — and likely many more than that! — in order to see the else, or not.

To remove this sort of ambiguity, we can use one of the techniques we used for left recursion: factor the common start of the two rules into one new rule:

statement := if expression

then statement

statement-rest

statement-rest := else statement

| ε

The choice now becomes part of the second rule, which the parser does not encounter until after having matched the common "prefix".

But doesn't the ε rule create a new form of nondeterminism? In this case, never. If the parser sees an else token next in the stream, it uses the first rule. If not, it uses the second. That won't be a problem in any language I know, because an else token cannot start a new statement.

In general, though, this does create a potential problem. In

most languages, we are able to make the choice

deterministically by peeking ahead to what can follow

a statement. We will learn more about this idea

soon.

Note that this technique is much like factoring duplication out of code and isolating it in a new function. It's just that here, we create a new grammar rule!

This factoring technique creates a new non-terminal in order to eliminate an ambiguity. It is an instance of a more general strategy of creating 'marker' non-terminals that help a grammar remember higher-level structures. We won't look at more general uses of this idea this semester, but the Klein grammar uses marker non-terminals to ensure the language's precedence rules.

Exercise: An Ambiguous Grammar

S := ( L ) | a L := L , S | S

This grammar is ambiguous, which makes it hard to write a deterministic parser for the language.

Eliminate the ambiguity.

What language does this grammar specify?

If you aren't sure, try running this random string generator that follows the grammar.

Solution: An Unambiguous Grammar

First, eliminate the left recursion that allows a parser to recur infinitely:

S := ( L ) | a L := S , L | S

That is a simple change, huh? It requires a little thinking,

though, about what can be derived from L.

Then, left factor the resulting grammar that allows a parser to choose non-deterministically:

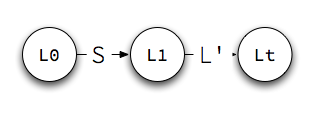

S := ( L )

| a

L := S L'

L' := , L

| ε

By examining the rest of the grammar, we can see that

whenever we use the ε substitution, the next character in

the string must be a ). All that really matters,

though, is that it cannot be a ,. This

assures us that the parser can choose deterministically.

Now we have a grammar for the same language in a form that we can use to build a simpler parser for it.

Creating a random Klein program generator like the one above would be a fun exercise — and open the door to some interesting ways to test our compilers using a technique called fuzzing.

Recap: Building a Parser

We are discussing the syntax analysis phase of a compiler. Last time, we learned a few things about languages and grammars that will help us build parsers.

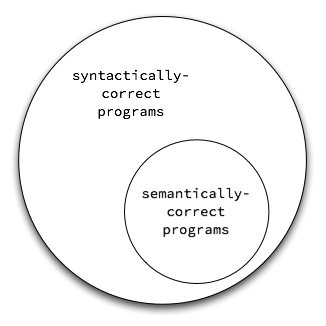

First, programming languages are context-sensitive. Unfortunately, context-sensitive grammars are difficult to parse, making them inefficient.

To avoid this, we model programming languages with context-free grammars and augment the grammar with notes about the context-sensitive features of the language. When we use a context-free grammar as a model for a programming language, the set of syntactically-correct programs is a superset of the set of legal programs. To address this issue, we will follow the parsing step with a semantic check.

Second, some grammars are ambiguous, because a legal program has two different but valid parse trees. Such ambiguities make it difficult for a parser to know how to proceed without the risk of having to backtrack. In order to make the grammar unambiguous, and our parsers more efficient, we eliminate these ambiguities.

We can think of the techniques we saw early in this session as

removing ambiguities from the beginnings of grammar rules.

They often introduce potential ambiguities at the ends of the

rules with ε's. We'll have to make sure that

there are no ambiguities there before we have a way to implement

a parser that can proceed efficiently.

With a context-free grammar as our model of the syntax of programming languages, we will use a pushdown automaton to model the recognizer for a language.

Strategies for Parsing

The next question is practical: how can we use a pushdown automaton operating over a context-free grammar to write the parser for a language?

There are two basic strategies in practice:

-

Make it the parser's goal to recognize an expression that

matches the start symbol. If we encounter a non-terminal

in the process of doing this match, then the parser creates

a subgoal: recognize an expression that matches the

non-terminal. It must satisfy the subgoal before proceeding.

If we reach the end of the stream and have satisfied all the

subgoals, then we have recognized a valid program.

This is goal-oriented parsing. If we look at the hierarchy of goals that this process creates, we see non-terminals at the internal nodes of the tree, with symbols encountered early in the search higher in the tree than symbols encountered late in the search. As a result, this strategy is usually called top-down parsing. -

Read the token stream without pursuing a specific goal.

After each step, check to see if the text read thus far

matches the right hand side of any production rule. If it

does, replace the matching subsequence with the

corresponding non-terminal symbol. If we reach the end of

the stream and have replaced all the symbols sitting in the

stream with the start symbol, then we have recognized a

valid program.

This is opportunistic parsing. If we look at the hierarchy of non-terminals recognized in the process, we see low-level symbols matched first, and only lower in the tree do we see the symbols that 'contain' them. Thus, this strategy is usually called bottom-up parsing.

There is a third general class of parsing techniques called universal parsing. These include the Cocke-Younger-Kasami and Earley algorithms, which use a form of dynamic programming in addition to other tools. Universal parsing techniques work for a wide variety of context-free grammars, but they are too inefficient and too opaque to use in a production compiler. The more efficient top-down and bottom-up algorithms work only for a subset of grammars, but they are sufficient for the purpose of compiling programming languages.

In both top-down and bottom-up algorithms, the parser may want to peek ahead some number of tokens in order to choose its next step. In principle, a parser might look ahead any number of tokens. However, the more tokens it looks ahead, the less efficient it will be. It turns out that we can create efficient parsers that look ahead only one token and are able to recognize the programming languages that most people can understand and use. From now on, we will consider only algorithms that require a lookahead of only one token.

Bottom-up algorithms are complex enough that writing them by hand is rather difficult. As a result, most parsers written by hand work top-down. Parsers generated by tools may parse either top-down or bottom-up.

For reasons of both time constraints and complexity, we will focus our attention on top-down parsing in this course.

Recursive Descent Parsing

The simplest kind of top-down parser uses a technique called recursive descent. This is the strategy we saw in the Fizzbuzz compiler (zip) we studied earlier in the course.

Recursive descent follows two basic ideas:

- Begin with the goal of matching the start symbol to the stream of tokens, and work toward the terminal symbols it contains.

- Match each non-terminal by calling a procedure that implements a finite-state machine.

To build a recursive descent parser, we write one function for each non-terminal. The task of each function is to determine if the sequence of tokens being processed is an instance of that non-terminal.

- When it encounters a terminal token, it can match the token directly, often by testing for equivalence.

- When it encounters a non-terminal, it calls the function that recognizes that non-terminal.

Thus, the matching process "descends" down the goal tree by making function calls. Eventually, it reaches the leaves of the tree, which are themselves terminals.

While simple, recursive descent is powerful enough to be used to write parsers by hand for many interesting programming languages.

As an example, take a look at the functions defined in the Fizzbuzz parser:

-

match non-terminals

parse_program()parse_range()parse_assignments()parse_assignment()

-

match terminals

match()match_number()match_word()

There is one procedure for each non-terminal in the grammar.

parse_assignments() is recursive. There are

three match???() procedures, which directly match

the terminal tokens in a grammar rule.

In general, recursive-descent procedures may be recursive, or

mutually recursive with other procedures, because one kind of

statement can contain another instance of the same kind of

statement (for example, a nested if).

By making recursive calls within the implementing language, we do not have to implement and manage our own stack. The mechanics of recursive procedures creates and manages the stack of calls, saving the state of the caller when it tries to match a non-terminal and restoring the state of the caller when a called procedure returns. In other words, we use our implementing language's compiler's run-time system to implement a pushdown automaton for us!

This convenience comes at a heavy price: inefficiency in both space and time, related to the creation of activation records. Production compilers can be much more efficient, as long as they can choose their next action unambiguously. How?

Implementing a Predictive Parser Using State Machines

The Idea

Recursive descent is not the only way to write a predictive parser. We can implement a non-recursive parser using a collection of finite-state machines, by implementing and maintaining our own stack of states.

As is often the case, careful construction of a pushdown automaton by hand can create a more efficient parser than what is produced implicitly by executing recursive procedures in the implementing language.

To implement such a parser, we build a state machine for each non-terminal in this way:

- Create a start state and a terminal state. The terminal state is the state from which the machine can return to the machine that called it.

-

For each production

A := X1 X2 ... Xn, create a path of states from the start state to the terminal state with the edges labeled by theXi.

A parser using these transition diagrams begins in the start state of the start symbol of the grammar. It changes from its current state s based on the next token:

-

If the next token is the terminal

a, and there is a transition out of state s onato state t, then consume the token and move into state t. -

If the next token does not match any terminal

athat leads from state s, then the parser follows a transition labeled with a non-terminalAto state t.

In doing this, it does not consume the token. Instead, it changes to the start state of the state machine forA. If the program ever reaches a terminal state ofA's machine, it "returns" to state t. In effect, this "reads" anAfrom the input stream by consuming tokens thatA's state machine consumes. - If there is a transition labeled with ε to state t, change to state t without consuming any tokens.

This approach works only if the state machine is deterministic. For example, note in Step 2 that there can be only one transition out of state s labeled with a non-terminal. If there were more than one, how would the parser know how to proceed? Such a grammar would need to be disambiguated before being converted to state machines.

An Example

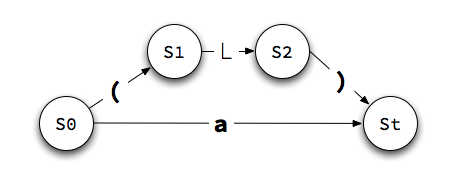

Let's see how this process works for the grammar you fixed up in our exercise, recognizing these strings:

(a)(a,(a))

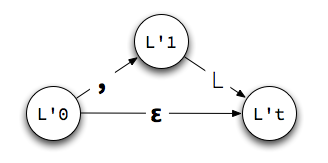

The state machines for the grammar at the right.

The process is mechanical and straightforward to follow. The only detail left to implement is the stack that keeps track of the state to return to when a machine reaches its terminal state.

Our left recursion and left factoring techniques often introduce ε-transitions, which can be a source of nondeterminism. Sometimes we can make an assumption that eliminates the non-determinism, if not the ε-transition itself.

For example, consider the state machine for L'. If we decide

that our parser will take the

, transition

whenever it can and take the ε-transition only when the

comma rule does not, we have eliminated the nondeterminism

with a rule outside the grammar.

This kind of assumption may affect the set of strings that can be recognized or the abstract syntax tree that the parser produces. We generally make sure that this doesn't happen before we decide to make the assumption.

But we often have a better alternative: For many languages, we can demonstrate that a ε-transition is not ambiguous, because the next token never conflicts with the other transition(s). This will be the approach we use to build a parser for your compiler. We will begin to learn this technique next time.

Table-Driven Parsers

The Idea

Given that this will be our approach — a top-down parser with deterministic state machines for each non-terminal and a stack for memory — how are we to implement our parser?

The main question to answer when implementing a parser using state machines and a stack is, What production rule should the the parser apply when faced with a transition labeled by a non-terminal? We will use a table to record how to make such decisions. The result is called a table-driven parser.

As a table-driven parser processes a stream of tokens, it uses two new data structures:

- a parsing table that records, for every combination of state and non-terminal, the production to apply, and

- a stack of states being processed at any given time.

The stack is dynamic, of course, growing and shrinking at run-time as the parser recognizes nested non-terminals. The table is static; it is built prior to processing and stays the same throughout each run of the parser.

We can think of the parsing table as a function

M that maps ordered pairs onto production rules.

The ordered pairs are of the form [N, t], where

N is a non-terminal and t is a

token.

When the parser is attempting to recognize an N

and the next input token is a t, it uses the

production rule recorded at M[N, t]. If

no production exists for the pair, then the table must

indicate an "error" value for that pair, either explicitly

or implicitly.

The Algorithm

Here is a simple table-driven algorithm. A parser using this algorithm refers to the current token t in the input stream and the symbol A on top of the stack, and continues until it reaches the end of the input stream, denoted by $.

- Push the end of stream symbol, $, onto the stack.

- Push the start symbol onto the stack.

-

Repeat:

-

A is a terminal.

If A == t, then- Pop A from the stack and consume t.

- Else we have a token mismatch. Fail.

-

A is a non-terminal.

If table entry [A, t] contains a ruleA := Y1 Y2 ... Yn, then- Pop A from the stack. Push Yn Yn-1 ... Y1 onto the stack, in that order.

- Else there is no transition for this pair. Fail.

-

A is a terminal.

This algorithm requires no recursion to recognize an input stream. It does not even make any function calls! Instead, it grows and shrinks a stack of states on its own and loops through entries in the table. The parse table embodies all of the knowledge that exists in the separate procedures of a recursive-descent parser.

This is the only algorithm we need to implement our parser. But it creates a subgoal for us, which is our next task: Learn how to construct the parsing table M.

We will learn that in our next two sessions.