Session 1

An Introduction to Compilers

Opening Exercise

Welcome to CS 4550! I am very happy to have you in class. I think we will have a great semester together.

Let's start with a few thoughts about programming languages...

In your experience, which of these languages is the easiest to use? The hardest? Why?

Which of these languages do you imagine is the easiest to compile? The hardest? Why?

Is there a relationship between how difficult a language is to use and how difficult it is to compile? Why or why not?

After this course, I hope that you will have developed new intuitions about how your programming languages work. Oh, and you will have written a compiler.

Welcome to the Course

Welcome to CS 4550, formally titled Translation of Programming Languages. You and I will usually just call it "compilers", for reasons that will be obvious by the time you leave today, if not already.

This is one of the great courses in any computer science

curriculum. Some of you studied the concepts underlying all

programming languages in

CS 3540,

a course I called a pivotal point in your computer science

education

. Others have studied the theory of computation

in CS 3810, in which you learned about the relationship between

languages, machines, and computation. Still others come here

from CS 3530, where you learn that there are many kinds of

algorithms for many kinds of problem. Now you are ready to more

fully understand these concepts and relationships. And to write

a real program.

I am Eugene Wallingford, and I am your instructor for the course. You may find the course challenging, but I also hope that you find it fascinating. My greatest hope is that it changes how you think about programming languages, the language processors we use, and what it is like to write a large program.

This an exciting course because it is where the "high priests of computer science" reveal the rest of their secrets. A course in programming languages teaches us that the tools we use to process our programs are just programs, like any others. There, we study some of the basic concepts of programming languages by working with a simple form of a language processing program, an interpreter. A course in theory teaches us how our programs relate to more abstract mathematical concepts, and what those concepts can tell us about programs. There, we learn that computation is possible by implementing "machines" that transform strings into other strings. A course in algorithms teaches us that data structures and algorithms, taken together, can help us implement solutions to just about any problem.

This course is a natural continuation of these courses.

But the interpreters you see in Programming Languages often avoid important details of language by simplifying the problem they address. The machines you see in Theory of Computation are theoretical constructs only, far removed from the languages in which real people write real programs. The algorithms you see in Design and Analysis of Algorithms are also mostly theoretical, studied in the abstract, and not focused on any particular problem.

This semester, we attack the full complexity of processing a language head-on by studying and implementing a program that translates other programs into an executable form. This translator must generally deal with the full range of issues involved in executing a program on a digital computer — from processing syntax, through processing abstract syntax and semantics, to generating code for a target machine.

Along the way, we will consider other issues such as handling syntactic abstractions, processing a broader class of languages, and optimizing the execution of generated programs. As we do, you will come to appreciate at a new level the role of language in computing, the mathematical foundations of computation, and the interaction between program and machine. Along the way, you will come to appreciate in a new way the value of good programming practice.

What is a Compiler?

"A compiler is a function that turns

a sequence into a tree, that tree

into a graph, and that graph

back into a sequence."

Programmers write programs using what we call a source language. The result is the source code of the program. In older days, programmers used to speak of "writing a new code" when they were writing a program. You can still hear such language from non-programmers, especially in TV and movies, such as The Imitation Game. My mathematician and physicist friends sometimes speak this way; I often hear my British colleagues speak of "a source code" or "the codes".

Of course, we create source languages for human programmers to use and understand, not for computers. Like so many things in computing, though, this is an oversimplification. Over the course this semester, you will see many ways in which our programming languages compromise between what is good for people and what is good for computers.

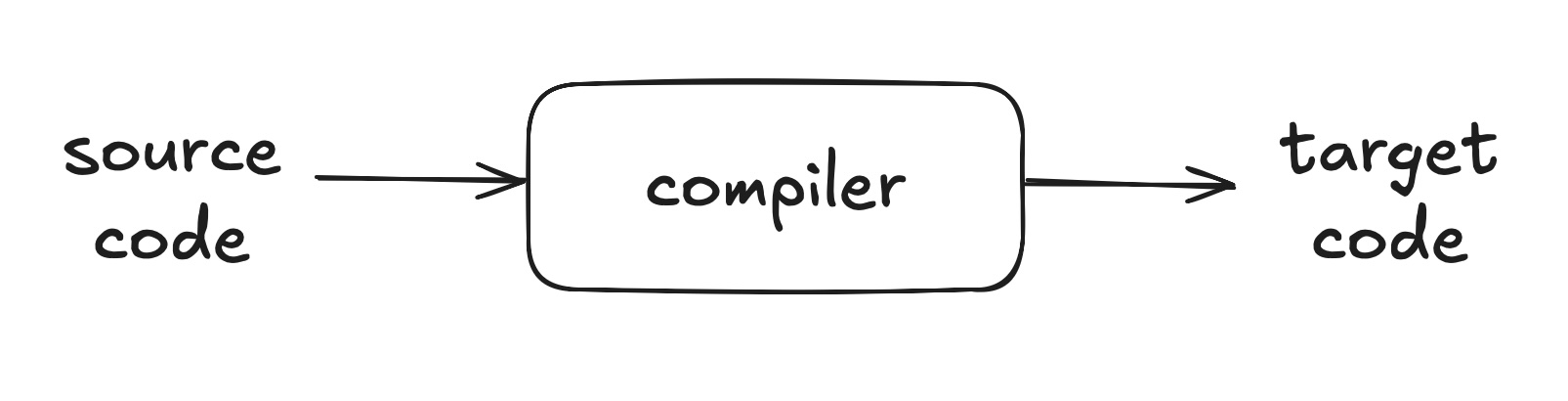

Compiler as Black Box

Someone or something must transform the source code into a code the computer can execute:

In the original and most specific sense of the term, that's what a compiler does: translate the source code of a program into machine language, which is run directly on a machine, on "bare metal".

In practice, there are many other kinds of program that behave like a compiler, translating source code into target code. For example, the target code needs to be executable in some sense, but it doesn't really need to be machine language.

- A compiler can generate code for a virtual machine, such as the Java virtual machine (JVM) or the Parrot VM.

- It may generate target code in another high-level programming language, such as C. Compiling to C is a common strategy for implementors of new languages, because C is small, relatively low level, and highly portable. The result is that the new language can be made quickly available in efficient form on a wide variety of machines.

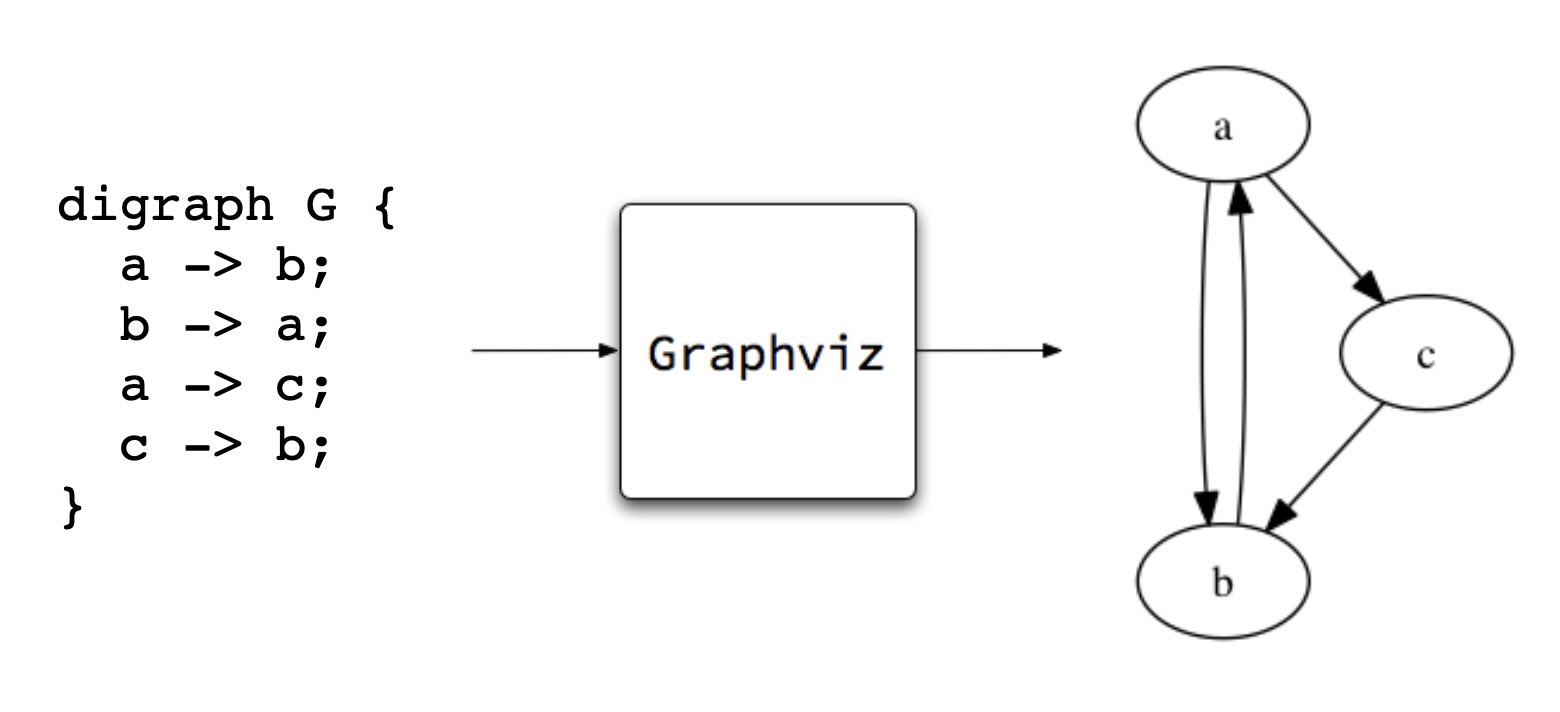

We can also loosen the definition of a compiler on the input side. The source code processed by a language translator need not be a programming language in the traditional sense. Humans create and use small, special-purpose languages all the time in order to express specific intentions, such as creating graphics. Consider Dot, a plain text language for describing graphs, and Graphviz, a compiler for Dot:

The Unix philosophy is built on the notion of little Languages that do one specific task very well. Languages that process text into graphics, bibliographic formats, and camera-ready documents were among the earliest programs added to Unix.

Under the hood, a compiler usually implements a sequence of transformations on the way to its result. This sequence of transformations generally consists of many of the same techniques and algorithms, whether the source language is a full-blown programming language or a special-purpose description language. In this course, we learn in detail what goes on inside that black box.

This session, we consider at a high level what a compiler does. Next session, we will turn our attention to the basics of how a compiler does what it does.

Compiler as Two Stages

If we look inside the compiler as a black box, we see that a compiler performs two basic tasks as part of any transformation:

- analysis — understand the components of the source programmer

- synthesis — generate the components of the target program

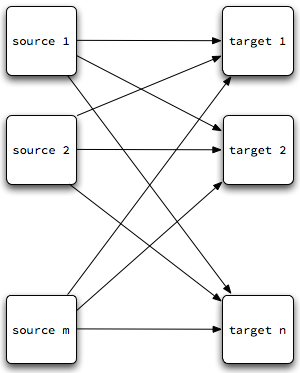

Why break the main task into these two stage? Early compilers sometimes did not separate them, or at least tightly coupled them. One result of such coupling is that writing compilers for m languages on n platforms requires m x n different compilers:

Each line in that diagram is a different compiler!

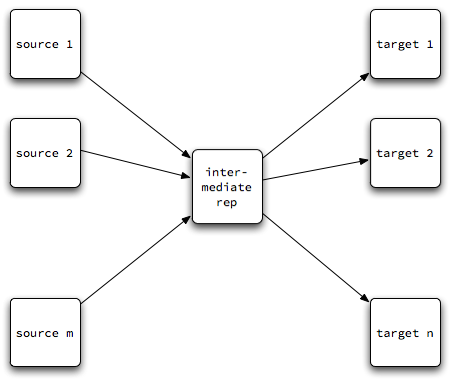

If we decouple the two stages by introducing a middle step, an intermediate representation, perhaps we can simplify both. In this way, writing compilers for m languages on n platforms might require only m "front ends" + n "back ends":

Analysis uses knowledge of the source language to decompose the source program into its meaningful parts. An abstract syntax tree can serve as a simple intermediate representation. Each line on the left side of this diagram is an analyzer.

Synthesis uses knowledge of the target language to translate structures in the intermediate representation into meaningful expressions in the target. Each line on the right side of the diagram is a synthesizer.

As noted earlier, the target languages can be:

- the machine language for a particular architecture — pure, or augmented with OS calls.

- the language of a virtual machine. This is 'machine code', but the machine is really another program — an interpreter! Smalltalk pioneered this idea, Pascal's P-code brought the idea into the mainstream, and Java capitalized on the idea.

- another high-level language. In such cases, we sometimes call the program a translator or a cross-compiler.

Many of the most successful programs are not compilers in the "translate to executable machine code" sense, but they rely on many of the basic techniques of a compiler. This is one of the reasons we named this course Translation of Programming Languages and not "Compilers". The latter is more traditional and is great shorthand, but there is so much more to what we learn than that.

Another Exercise

- Which part of the compiler do you think is harder to write, analysis or synthesis? Why?

- What do you hope to learn in this course?

- What is your biggest worry about the course at this point?

Don't be worried about having questions or concerns. I have been doing this a long time, and I have both.

A Quick Tour of the Course Details

The course syllabus contains basic information about me and the course. If you have had me for a course before, then this may look familiar. The course home page contains links to all of our activities, including lecture notes, the compiler project, and resources that we can use this semester. Bookmark the course web page in your favorite web browser. You never know when the urge to do CS 4550 will strike you!

I ask that you study the syllabus carefully. It lists the policies by which we will run this course. If you have had me for a course before, many of these will look familiar. You will want to know these policies and when they apply. A few highlights for now, starting from the course home page:

- The best ways to contact me are by e-mail and during my office hours. I am often in my office at other times as well. Some office hours may be virtual, and I'm sometimes available more often if you can meet virtually, too.

-

We have a course mailing list,

cs-4550-01-fall@uni.edu, through which we can discuss course topics, ask and answer questions, and so on. By default, you are subscribed to this listserv from youruni.edue-mail address. If you intend to read and write mail from some other address on a regular basis, please subscribe from that address. -

I suggest readings from a textbook that is available free

online, both on

its own website

and as

a pdf file on the course website.

Suggested readings will link directly to chapters on the

website. It offers one view of how to build a modern

compiler.

To be honest, this course doesn't rely much on the textbook. My lectures draw on several books and resources, and we will often go deeper on a topic than the Thain text. The lecture notes for the course are quite extensive, and I will sometimes provide handouts. Having a textbook to refer to can be comforting, though, so use it as source for basic context. You may certainly use other textbooks as supplements for the course, but you shouldn't need to. Read whatever you find helpful and ask questions. - The course homepage gives a tentative schedule for the semester, including project and homework dates. As the semester progresses, it will have links to notes for each class session as well as project assignments and any outside reading assignments.

- I have the same "Late homework is not accepted for grading." policy as in all of my courses, but a project course is different. We have several major milestones for the project, which I will evaluate and grade at the time. But the final product is more important than any of the individual milestones, and teams are encouraged to improve all phases of their compiler as they move ahead. We will talk more about the project in coming sessions.

Now, back to compilers...

What Does a Compiler Do?

Introduction

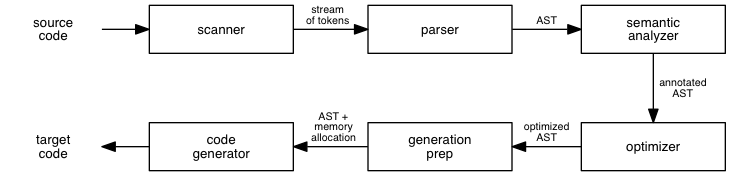

Earlier, we began our look at what a compiler does by decomposing the compiler as a single black box into a compiler with two black boxes: analysis and synthesis. Now, let's go farther and think of a compiler as a sequence of processes:

This is a simplification, much like the waterfall process in software engineering. The stages of compilation can interact with one another, so the process isn't always a pure sequence. The interaction between scanning and parsing is so strong that many compilers are parser-driven: the parser is the initial stage, and it calls the scanner whenever it wants another token.

(For you object-oriented programmers, this approach fits nicely with the notion that the scanner is an input stream, a decorator that produces tokens out of an underlying character stream.)

The order of the latter stages differs from textbook to textbook and from approach to approach. The most common differences involve the existence and ordering of preparation for code generation, initial code generation, and optimization. The Thain text includes all code generation in a single stage, with optimization out of the main sequence, where it can be iterated over multiple times.

Let's use the six-stage process above to help us understand what a compiler does, by tracing the process of compiling two simple lines of pseudo-code +:

I drew this code and much of the discussion in this section from Chapter 1 of Fundamentals of Compilers by Karen Lemone, CRC Press, 1992. It is available in the UNI library.

x1 = a + bb * 12; x2 = a/2 + bb *12;

Today, we will take a quick tour of the six stages to give you a better sense of what a compiler does. (In class, the tour is especially quick, just a feel for the stages. The notes below have more detail, which you can read on your own time.) Next time, we will look at an example of how a compiler implements the various stages, by looking at the code of a compiler for a small language. The rest of the semester then goes even deeper into each stage of the process.

Lexical Analysis

This stage of the compiler converts a stream of characters into a stream (or sequence) of tokens. A token is the smallest language unit that conveys meaning.

In our example code, the xs do not mean anything

at the level of the program, but x1 is a symbol

that acts as an identifier in the program. We might

guess from this code that x1 and

x2 are probably variables, but the

token-recognition process works only at the level of

individual units. The single

; character does

means something by itself: it terminates a statement. The

white space in the program does not mean anything; it merely

separates tokens.

Choosing tokens and spacing rules is an important part of language design, and doing it well depends much more on human psychology than on technical details of processing a language grammar.

The scanner reads the input stream until it identifies a token, and it then classifies the token by its type. The various token types available in common languages include:

-

literals, such as

12andtrue -

identifiers, such as

x1andScanner -

operators, such as

=,+andor -

punctuation, such as

;, and{, and) -

keywords, such as

whileandclass

So, a token is really an ordered pair consisting of its type and its value. The value may be optional if the token type conveys all the information we need to know about the token. The token is our compiler's first data structure!

Consider our example code. A scanner might convert this stream of characters:

x1 = a + bb * 12; x2 = a/2 + bb *12;

into this sequence of tokens:

IDENTIFIER x1 OPERATOR = IDENTIFIER a OPERATOR + IDENTIFIER bb OPERATOR * LITERAL 12 PUNCT ; IDENTIFIER x2 ... OPERATOR * ... notice, even though no space LITERAL 12 PUNCT ;

Now consider this example:

if newValue < 1 then ...

The tokens are a keyword, an identifier, an operator, a number

literal, another keyword, .... The scanner doesn't know that

newValue < 1 is a boolean condition;

it simply finds the tokens in the stream.

At this level, our compiler can find only the simplest lexical errors, such as misspellings. We could build, or at least begin to build, a table of the identifiers recognized (a symbol table), but this is usually done in a later stage, along with some related processing.

Syntax Analysis

The next stage of the compiler is syntax analysis. At its simplest, this stage determines whether a stream of tokens obeys the grammatical rules of the language. The output is a boolean value: yes or no. The result is a program that recognizes legal programs in a language.

A recognizer is of limited use if we want to execute the legal program it recognizes. So, this stage of the compiler converts the stream of tokens into an abstract syntax tree, or AST. The existence of the AST indicates that the program obeys the grammatical rules of the language, and the tree itself encodes the grammatical structure present in the program. The AST is our second data structure.

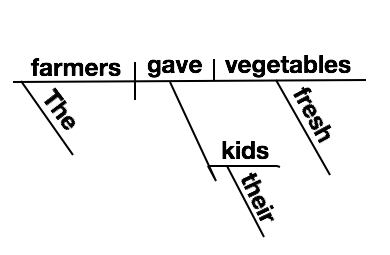

Parsing is like diagramming sentences in a natural language. In English, we can recognize a legal sentence by its composition as a noun phrase followed by a verb phrase. At this level, the compiler recognizes expressions, statements, blocks, procedures, classes, modules, and other meaningful units at the level above tokens.

We can parse a token stream using a number of different approaches, usually grouped as "top-down" and "bottom-up". Learning these techniques — and how to implement them — is a big part of a course on compilers.

A parse tree groups tokens into meaningful units but retains most of the syntactic detail, such as parentheses and statement terminators. It is the rawest way to begin grouping tokens into sentences.

An abstract syntax tree also groups tokens into sentences but retains only information about the statement or expression that is essential to understanding its meaning. It eliminates punctuation whose meaning is already conveyed by the tree's structure.

For example, the token stream for our sample code might be parsed into a parse tree such as this:

PROGRAM

ASSIGNMENT STATEMENT

EXPRESSION

IDENTIFIER x1

=

EXPRESSION

ADDITION EXPRESSION

EXPRESSION

IDENTIFIER a

+

EXPRESSION

MULTIPLICATION EXPRESSION

EXPRESSION

IDENTIFIER bb

*

EXPRESSION

INTEGER 12

;

ASSIGNMENT STATEMENT

EXPRESSION

IDENTIFIER x2

...

... and then into an abstract syntax tree such as this:

Notice that both of these trees reflect semantic information

such as the order of precedence on operators.

bb * 12 is to be computed first, and its value

added to a. This shows that the linear token

stream can be converted into a two-dimensional structure that

reflects the meaning of the statements.

Some compilers create a parse tree on the way to creating an abstract syntax tree, but many produce an AST directly.

Semantic Analysis

The semantic analyzer takes as input the AST and generates as output an AST annotated with new information. It usually also produces a symbol table that contains all of the user-defined identifiers that appear in the program.

This sort of static checking determines whether the tree represents a meaningful program. It usually involves some or all of:

- verifying that variables have been declared, if the source language requires declaration.

-

verifying that the operands to assignments and other

operations are of the proper types.

Consider the expressiona * b + c. The semantic analyzer checks to see that the operators*and+are defined for operands matching the types ofa,b, andc. It also has to ensure that the type produced by the operator with higher precedence produces a value accepted by the other operator.

(Is"a" + "b" * 12legal? It depends on the language...) - validating array references, such as ensuring the correct number of dimensions and flagging out-of-bounds references.

- verifying that a variable is not accessed until it has been initialized.

- suggesting that a variable can be given a different type based on its use, in the interest making target code smaller or faster.

Notice that a couple of these checks also add information to the AST. These annotations make the tree more useful when generating target code. Sometimes, this level of meaning is implicit in the programmer's mind when writing the code. For example, the programmer may know that the type of value produced by an operator can be generalized from an integer to a float. Sometimes, it is present only in the language designer's mind, as in the case of changing a variable's represented type for optimization.

In the static checking phase, the compiler can generate error messages for semantic problems in the program. These can be of great help to the programmer.

Consider our running example. The types associated with each

intermediate expression depend on the types of a

and bb. If either is, say, a boolean variable,

then both of these statements are probably illegal! If

a is a floating-point value, then statement 2 may

be illegal — if / is the operator for

integer division.

Of course, the compiler has to be able to show that under no circumstances does the value of the former get changed to something different from that of the latter. Perhaps now you can see how functional programming, with no side effects, can empower the tools that process programs!

Preparation for Code Generation

This phase of the compiler uses the abstract syntax tree to create a plan for allocating memory and registers at run-time. This plan is sometimes called a map, and is yet another data structure used by the compiler. The locations listed in the map will hold the code of the program and the values of identifiers at various times during execution.

One of the primary issues in memory allocation is choosing between static allocation (fixed at compile time) and dynamic allocation (determined at run time).

One of the primary issues in register allocation is making the generated executable run as fast as possible. Operations on registers are generally faster than operations on memory locations. Additionally, if an identifier can remain in a register for several operations, the code will run faster than if it has to repeatedly load registers and store their values out to memory.

A common approach is to assign registers and memory locations to variables in a preparation phase and then to generate target code with this information available to the code generator.

Unfortunately, we have a chicken-and-egg problem. To generate the best target code, we need to know how our registers and memory locations to be used; but to select registers and memory locations in the best way, we need to know what the target code looks like!

Registers are a scarce resource. RISC machines have more registers than older architectures, but there usually still are not enough of them for the many partial computations even a small piece of code does. Good register allocation often contributes a better performance improvement than code optimization.

Some compilers assign temporary registers and memory locations during a preparation phase, and then modify them as they learn more about the target code during code generation.

For our code example above, a compiler might allocate memory and registers in this way:

-

memory — allocated on the stack

- a [top]

- bb

- address of x1

- address of x2

-

registers — we can get by with three

- stack top

- bb * 12

- a and then a/2

By using Register 3 for both a and

a/2, the target code can avoid loading

a into another register by doing a fast

right-shift operation.

Code Generation

Code generation takes as input an intermediate representation of the program (an optimized AST) and the memory and register allocation map produced in the preceding phase. It produces as output code in the target language. This is, of course, often assembly code.

You've written some assembly language, so you know that each statement in our AST requires several lines of machine code. The key to generating good code is the selection of efficient, small sequences of assembly code to implement each operation. We sometimes do this by having code templates for each kind of operation, which we know to do a good job in the general case. The generator can specialize this code for any peculiarities of the source code in question. A target code optimizer might do even more of this.

Note that readability of the generated code is usually of no importance. An especially tricky piece of code is preferred if it is smaller and faster than the alternatives. We can comment this code if we really want humans to be able to read it. (This is one of the good uses of comments: to explain a piece of code that needs to be written in a way that is not obvious or easy to understand.)

For our code example above, a code generator might produce assembly code of this sort (comments added for your sake):

PUSHADDR X2 ; put address of X2 on stack PUSHADDR X1 ; put address of X1 on stack PUSH bb ; put b on stack PUSH a ; put a on stack LOAD 1(S),R1 ; bb → R1 MULT #12,R1 ; bb * 12 → R1 LOAD (S),R2 ; a → R2 STORE R2,R3 ; copy a → R3 ADD R1,R3 ; a + bb * 12 → R3 STORE R3,@2(S) ; X1 ← a + bb * 12 DIV #2,R2 ; a/2 → R2 ADD R1,R2 ; a/2 + bb * 12 → R2 STORE R2,@3(S) ; X2 ← a/2 + bb * 12

The particular details of this fictional assembly language

used here are not important. But notice that the optimized

code is computed once into R1 and used twice.

Notice, too, that a is used from R2

in the first computation and then halved for use in the

second. These result from the optimization phase and the

register allocation phase that preceded code generation.

A Taste of What's to Come

Here is a source program written in the programming language you will be compiling this year.

Here is an assembly language program generated by the sort of compiler that you will be writing this semester.

The compiler that generated this assembly language code was written by a team of students in a previous offering of this course. They were compiling a different source language, but the program being compiled was semantically identical to the source program linked above.

You can do this.

Why This Course Is Good For Every CS Major

Many (most?) of you will not a compiler in your career. Why learn to write one now?

Compilers, like operating systems, involve nearly every aspect of computer science:

- algorithms (scanning, parsing, program analysis, ...)

- data structures (tokens, syntax trees, symbol tables, ...)

- theory of computation (grammars, automata, ...)

- programming languages (semantics, type checking, ...)

- systems (assembly code, linking, ...)

- software engineering (debugging, testing, teamwork, ...)

- security (reverse engineering, stack smashing, ...)

We will talk about all of these topics, at least a little.

In the old days, CS undergraduates implemented several software systems: a compiler, an operating system, a database management system... As these systems grew larger and more complex, that became difficult.

When I was an AI student... Forward and backward rule chainers. A Prolog system. A means-end analysis engine. A truth management system.

In some courses, we can implement components, even substantial parts of a system. With well-chosen source and target languages, we can build a complete compiler in one semester.

This course offers practical benefits to every CS grad.

Writing a compiler is a great way to demonstrate to employers that you are capable of doing a substantial programming project.

In this course, you will write a big program. Writing a big program teaches you things about software development that writing oodles of small programs cannot.

In this course, you will write a real program. I could ask you to write almost any big program, but there is greater benefit in writing a program that uses your computing knowledge to accomplish a desired goal. This program will use knowledge from throughout your CS experience.

Computer science is about language. This course teaches you about language in ways that other course do not, in part because it builds on so many other courses.

Software development is program transformation. Understanding program transformation — what a compiler does! — can make you a better programmer.

Tackling a big project helps us grow in other ways. Listen to Joe Armstrong, the creator of Erlang, in this passage from the book Coders at Work:

It's a motivating force to implement something; I really recommend it. If you want to understand C, write a C compiler. If you want to understand Lisp, write a Lisp compiler or a Lisp interpreter. I've had people say, "Oh, wow, it's really difficult writing a compiler." It's not. It's quite easy. There are a lot of little things you have to learn about, none of which is difficult. You need to know about data structures. You need to know about hash tables, you need to know about parsing. You need to know about code generation. ... Each of these is not particularly difficult. I think if you're a beginner you think it'd big and complicated so you don't do it. Things you don't do are difficult and things you've done are easy. So you don't even try. And I think that's a mistake.

Things you have never done look difficult. Things you have done look... doable, if not easy. Give yourself permission to do it!

Next Session: An Implemented Compiler

Next session, we will take the step from what a compiler does to how a compiler works. We will do so by studying a small compiler, for a simple language, dubbed Fizzbuzz. Download the zip file and expand it for deeper study. You will find more details in Homework 0.

You certainly don't need to understand all of the details of this compiler. Try to get a sense of the basic flow of processing and the algorithms in the code. As you study, make note of any questions you have! We will try to answer them next time.

Wrap Up

The journey begins. I look forward to it.