Session 29

Optimization and Programming

And You Thought Module 4 Was Bad

TypeScript has a 33,836-line type checker. It's so big — 1.92 megabytes — that Github refuses to display it.

Optimization Redux

Last week, we considered a few ways in which a compiler can optimize the code it generates. As we learned, an optimization is nothing more than a program transformation that trades one cost for another, while preserving the meaning of the program. A compiler can make these improvements at multiple levels: source language, AST, IR, or even target language. Most optimizations work best at the AST level or in a well-designed IR.

Over the last two sessions, we have considered three classes of optimization:

-

optimizing loops, in particular by

unrolling

forloops into repeated statements and then modifying howwhileloops branch - optimizing function calls by inlining the function body in place of the call, and

- optimizing tail recursive calls by converting the call into a goto.

Handling recursive calls in tail position properly offers an inordinate payoff in languages such as Klein, which depend so heavily on function calls for iteration.

The run-time advantage of properly handled tail-recursive calls is so great that programmers sometimes choose to rewrite programs that are not tail-recursive so that they are.

Consider an old standard,

factorial:

function factorial(n: integer): integer

if (n < 2)

then 1

else n * factorial(n-1)

This function waits until n becomes 0, and then

starts a chain of multiplications at 1 that unwinds all of the

recursive calls. In a language with loops, we would implement

a much more efficient solution that iterates from

n down to 0. We can do the same thing in a

functional languages by making factorial tail

recursive:

function fact_aps(n: integer, acc: integer): integer

if n = 0

then acc

else fact_aps(n-1, n*acc)

Instead of saving the multiplication to be done after the called function returns, this function does the multiplication right away and passes the partial result along as a second argument.

As we saw last time, this function is, or can be, a loop. It's a simple conversion:

L1: IF n != 0 THEN GOTO L2 T1 := acc GOTO L3 L2: T2 := n - 1 T3 := n * acc PARAM T2 → n = T2 PARAM T3 → acc = T3 T1 := CALL fact_aps 2 → GOTO L1 L3: RETURN T1

Writing this version of the function requires the programmer to think differently, but in languages like Klein we often find ourselves writing tail-recursive functions as a matter of course. Consider this function, which I wrote as part of a program to compute the average digit of a Klein integer:

function average_digit(n: integer, sum: integer, i: integer): integer

if n < 10

then print_and_return(sum+n, i+1)

else average_digit(n/10, sum + MOD(n,10), i+1)

It implements something like a while loop to count

the digits in a number and sum them up along the way. I didn't

try to write a tail-recursive function; it's the most natural

way to write this code in Klein.

Sometimes our compilers optimize code for us, and sometimes we write code that runs quickly already.

Non-recursive Tail Calls

But it gets even better... Consider this Klein function from the sieve of Eratosthenes, which is not tail-recursive:

function sieveAt(current: integer, max: integer): boolean

if max < current

then true

else doSieveAt(current, max)

Though sieveAt is not recursive, its "tail

position" consists of a function call. The result of that

call will be returned as the value of the call to

sieveAt.

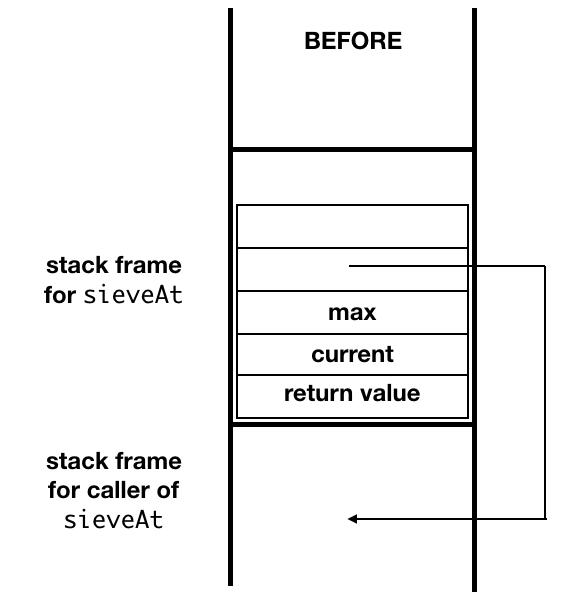

In this case, though, the called function's activation record does add value to the computation. It is the calling function's activation record that is no longer needed. It is simply a placeholder used to pass through the result of the called function to the caller's caller.

In this case, it is possible to pop sieveAt's

stack frame before the invocation of

doSieveAt, rather than after

sieveAt returns. This idea generalizes the

idea of "eliminating tail recursion" to

the proper handling of tail calls.

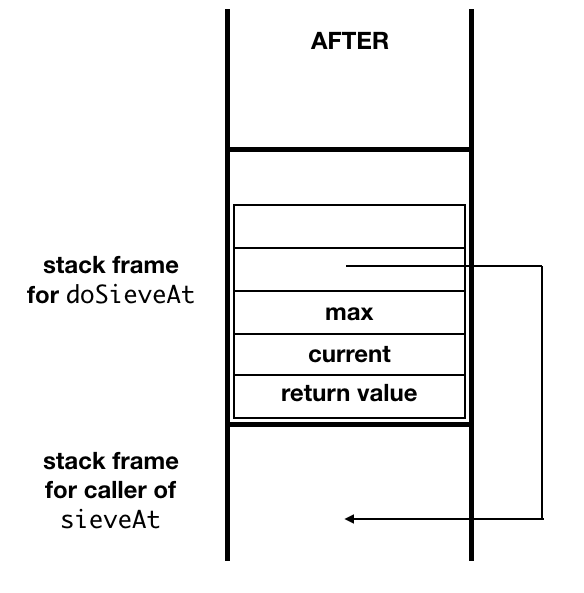

In calling doSieveAt, the target code for

sieveAt can:

-

prepare the arguments for

doSieveAt, -

create

doSieveAt's activation record, setting the control and access links in to point back tosieveAt's caller, - discard its own activation record,

-

place

doSieveAt's activation record on top of the stack, -

and invoke

doSieveAtwith a unconditional jump rather than a procedure call.

When doSieveAt returns, control will pass

directly to code>sieveAt's caller.

If a function invokes itself in a tail position, then tail-call optimization becomes a tail-recursion optimization.

There are two steps to implementing this technique:

- detecting the tail call and

- implementing the more efficient code.

Both are relatively straightforward to implement. It is remarkably valuable for optimizing programs written in a functional language, or in a programs written in an imperative language using a functional style.

Some functions that don't look like they make tail calls actually can. Consider that this Klein function:

function horner(x: integer, n: integer, value: integer): integer

if (GE(n, 0))

then horner(x, n - 1, (value * x) + coefficient(n))

else value

is equivalent to this one:

function horner(x: integer, n: integer, value: integer): integer

if n < 0

then value

else horner(x, n - 1, (value * x) + coefficient(n))

Very nice. How easy do you imagine it is for static analysis of a function to detect such a case and convert it to the equivalent tail-call function?

This all sounds so good, why would anyone not optimize tail calls away? First of all, these transformations may impose trade-offs that the programmer does not want to make. Handling tail calls in this way saves space on the run-time stack, but for a variety of reasons it can lead to slower programs at run time.

Secondly, and more important, there are issues that complicate the proper handling of tail-calls, which make it difficult or impossible to implement correctly. For example, in languages such as Java and C++, these include:

- the order in which arguments are evaluated. What happens if overwriting one argument changes the computation of another?

- the invocation of constructors and destructors of objects in dynamic memory.

Interested in learning more about tail call optimization?

These articles talk about tail call optimization in JS6, the most recent version of Javascript:

This discussion thread includes the source of one of my examples and gives some examples of why imperative languages such as C and C++ cannot eliminate tail calls, due to side effects in argument calculations, constructors, and destructors.

The Other Side of Optimization

The last two examples show that programmers sometimes implement

optimizations by hand. In the old days, programmers

occasionally unrolled loops by hand in order to improve

performance. In my work with Klein, I have frequently converted

if statements to boolean expressions, folded two

function calls into one by substituting values by hand, and so

on. I've also gone the other direction. But I would certainly

like for my compiler to optimize the code it generates so that

I don't have to worry about such matters.

Or do I? Can we take optimization too far?

Consider the case of

the C strlen() function

we encountered earlier. In order to make that call constant

and lift the invariant code out, we would have to tighten C's

language spec in several ways. Not everyone wants to give up

the freedom that C gives us. The point is more general than C,

though, as

this Hacker News comment

says:

And here is where the "optimizing compiler" mindset actually starts to get downright harmful for performance: in order for the compiler to be allowed to do a better job, you typically need to nail down the semantics much tighter, giving less leeway for application programmers. So you make the automatic %-optimizations that don't really matter easier by reducing or eliminating opportunities for the order-of-magnitude improvements.

The writer of that paragraph is not a low-level C programmer: he is a hard-core Smalltalk programmer.

As one compiler writer says, implementers of optimizing compilers face a lot of challenges dealing with programmers (emphasis added):

It's important to be realistic: most people don't care about program performance most of the time.

This author suggests that we keep our compilers and optimizers simple and powerful — in the small.

But let's not lose sight of how wonderful we programmers have things now. Most compilers, from LLVM and the standard Java compiler to compilers for languages such as Rust, Haskell, and Racket optimize code so well that we often need not think much about the speed or size of our compiled programs: they are already amazing. And that is a tribute to the code generators and optimizers in the tools we use, and to the researchers and implementers who have helped create them.

Examining Code Efficiency in TM

How can we tell if an optimized TM program is better than the original?

One way is to examine the size efficiency of our compiler by looking at the size of the code it generates:

-

the number of statements in the generated

.tmfile.

Statements in TM assembly language include line numbers, so we don't even have to count. -

the number of bytes in the compiled code.

Before doing this, though, we would want to remove all the comments from the generated code. This does not give us a whole lot of new information over the number of statements, because all TM instructions have basically the same length.

We can also examine the time efficiency of our compiled code. Two possible metrics are:

-

the number of statements executed at run time.

The TM simulator reports the number of statements executed on each program run. (You can use thepcommand to toggle that option off and on.) -

the amount of time needed to run a program.

To examine our generated code's run time at this level of granularity, we need a way to capture the clock time of a program's execution.

To support the last of these, former students and I have extended the TM simulator with a clocking mechanism that reports actual run time in the simulator, in milliseconds. You can download this version of the simulator from the project page.

In general, some machine instructions instructions take longer to execute than others. Capturing simulator run-time provides a proxy for that. For a more accurate representation of execution time, we would want to count execution time differently for the different kinds of instruction, say, RM instructions versus RO instructions and MUL/DIV instructions versus ADD/SUB instructions. We could build profiles for these instruction types based on an actual machine and then create a TM simulator capable of reporting that data. +

This would be a nice project!

Fortunately, we have a suite of benchmark programs...

Extending Klein

As I've mentioned in class this semester, I enjoy programming in Klein. My last two forays, over Thanksgiving break, were a program to compute the series 1/4 + 1/16 + 1/64 + ... for a given number of terms and a program to demonstrate a feature of certain fractions with repeating decimals.

I like to program.

Many programs would be easier to write if Klein had a

for loop, though

writing tail-recursive code

becomes a matter of habit. But some problems really

demand an array.

Klein is small, designed specifically for a one-semester course in writing a compiler. To use it for a wider range of problems, we would need to extend it.

Consider this list of features we might add to Klein:

- a for loop or a while loop

- an array data type

- local variables

- an assignment statement

What would you have to change in your compiler to implement this feature? Do we need more knowledge, or do we need only more time?

The language feature I most covet, I think, is an

import feature, such as:

from [file] import [function]

How hard would such a feature be to implement? We have all

the machinery we need: open the imported file; scan, parse,

and semantic-check it; copy the requested function's AST into

the AST of the importing file. We could create a simple

preprocessor to do this. Or we could create a preprocessor

to find and substitute the text of a function for the text of

the import statement, and then let the usual

compilation process take place.

Time or knowledge? It may be surprising to you just how useful the knowledge you already have is. Time is the more limiting factor for adding many new language features.

We will revisit this question in an exercise at the beginning of our next session.

Finishing the Project

Module 7 is the final stage of the project. It asks you to put your compiler into a final professional form, suitable for users outside of this course.

Make sure your system meets all functional requirements. Check all previous project feedback and address any issues. Be sure that your compiler catches all errors, whatever their source.

Make sure your project directory presents a professional

compiler for Klein programmers to use. The README

file should suitable for new users unfamiliar with this course.

It should describe the tools it provides and explain how to

build and run them. It should also provide a high-level

explanation of the contents of the subdirectories. You do

not have to list or explain every file in the folder.

There should not be any extraneous files in the directory:

no config files for VS Code or any other tools you used as

developers. This software is for Klein programmers. The files

in the doc/ folder should have clear, consistent

names.

You also have an opportunity to improve the system in some way, such as an optimization or a better component for one of the existing modules. This step is optional and will earn extra credit.

Evaluation

Recall how grading works for the project:

6 stages x 20 points each = 120 1 project x 130 points = 130

So, 250 points for the compiler itself, plus 25 points for the presentation and 25 points for project evaluations = 300 points total.

The 130 points for Project 7 looks a bit odd, but keep in mind that this involves evaluating the entire compiler again, from the scanner through the code generator, at 20 points per stage. All of the bugs you fixed in previous stages are now gone, so you have an opportunity to score (close to) 20 on those earlier stages. The extra ten points are for the state of the project directory.

If you submit an optimizations after the deadline, you will receive extra credit. I'm a nice guy, and I love optimizations. Early in finals week is the latest we can go.