Implementing Semantic Actions and ASTs

in a Table-Driven Parser

Representing Semantic Actions in a Program

The next pragmatic challenge is implementing semantic actions in your parser. What are some alternatives? I can think of a few.

In a procedural style, we might implement them as enums,

ints, or char to be switched on. For

example:

//

// in a helper function called by the parsing algorithm

//

switch (semanticAction)

{

case MAKE_IDENTIFIER:

value = lastToken.semanticValue();

node = new IdentifierNode(value);

semanticStack.push(node);

break;

case MAKE_ADDITION:

right = semanticStack.pop();

left = semanticStack.pop();

node = new AdditionNode(left, right);

semanticStack.push(node);

break;

...

}

...

//

// in the parsing algorithm

//

applySemanticAction(semanticAction, lastToken, semanticStack);

In a functional style, we might make the semantic action a function pointer or an index into a table of function pointers. Once we have the function pointer, we call the function with the semantic stack as an argument.

Once we have gone that far, we are close to...

In an object-oriented style, we can make our semantic actions objects to which we send a message. This approach uses the command pattern.

public class MakeIdentifier implements SemanticAction

{

public void updateAST( SemanticStack s ) {

value = lastToken.semanticValue();

node = new IdentifierNode(value);

s.push(node);

}

}

public class MakeAddition implements SemanticAction

{

public void updateAST( SemanticStack s ) {

right = s.pop();

left = s.pop();

node = new AdditionNode(left, right);

s.push(node);

}

}

...

//

// in the parsing algorithm

//

semanticAction.updateAST(semanticStack);

Channel your inner Woz, and ask questions when you have them.

Representing the Abstract Syntax Tree in a Program

Finally, there is the abstract syntax tree itself. We can represent an AST and its nodes in many different ways. At two ends of a spectrum are:

- as records or structs or tuples ("dead data") that will be processed by external procedures

- as objects ("live data") that have methods for responding to requests themselves

The choice between data and objects reflects a larger-scale design decision between programming styles that you first encounter in Intermediate Computing. This decision involves a set of trade-offs:

-

With dead data, it is relatively easy to add new behaviors

to the program, but not new types of things. We can add a

new behavior by writing a new procedure, which will switch

on the type of argument it receives. To add a new type of

thing, we must modify every procedure that processes

things, adding an arm to each switch for the new data type.

We saw this when we added semantic actions — a new kind of grammar symbol — to our table-driven parser. - With objects, the opposite is true. We can add a new kind of thing simply by creating a new class that contains a method for each kind of behavior in our system. To add a new behavior, though, we must modify every class, adding a new method for the new behavior to each.

In many large systems, especially ones that model parts of the external world, this trade-off can favor an object-oriented approach. But when implementing language processors, many people find that the balance shifts toward a procedural approach. Why?

It turns out that we are far more likely to know up front all the types of things we need to represent in our AST than we are to know all the kinds of behaviors we might want to implement on the tree. After all, the language grammar specifies the syntax of our language from the start! The grammar may change, but it usually changes infrequently relative to the number of processing tools that we may want to write.

For example, consider code generation. While you are not likely to add a new kind of expression to the abstract syntax of a language, you may well want write a new code generator, either to target a new machine or to experiment with a new technique. That's a modification of behavior, which would require a change to every class in an OO abstract syntax hierarchy.

Whatever representation we choose, it must support downstream processing. The later stages of a compiler must read and modify the abstract syntax of a program in several different ways, some perhaps not anticipated by the compiler writer.

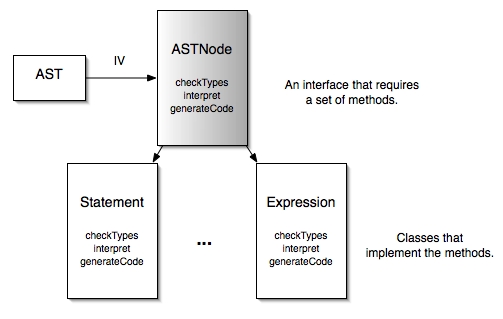

An object-oriented approach to abstract syntax will create a common interface for nodes in the abstract syntax tree and different classes for each kind of node. The AST of a program will be a composite, with compound expressions and statements that group particular configurations of nodes and with simple expressions such as literals and identifiers as "base cases".

This configuration of classes is so common in the OO world that it has a name, too: the composite design pattern.

You can see how, in a context such as compiler construction, the negatives of this approach begin to offset its positives. Because we are much more likely to implement new behaviors (analysis tools) han types (kinds of nodes in the tree), implementing compiler behaviors as methods requires that we continually modify and recompile all the files that define abstract syntax nodes.

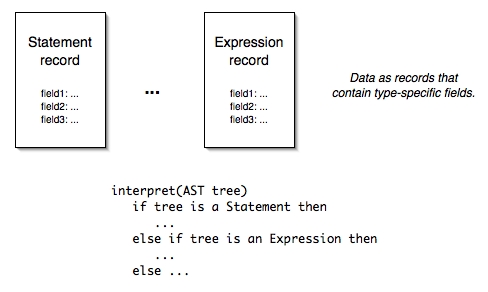

A pure procedural approach implements behaviors that manipulate an AST as switches on node type, typically with recursive calls to manipulate the components of node. The AST will be some sort of record or structure that groups data but embodies no behavioral knowledge.

Many compiler writers prefer this approach to the OO approach, even though its negatives also nearly offset its positives. In a statically-typed language, this approach requires frequent up- and down-casting of records in order to operate on them. Type checking in the compiler itself becomes a programmer concern, not a compile- or run-time concern.

Can we achieve the best of both worlds? To do so, we need a way to add behavior for manipulating ASTs without having to modify the ST classes themselves. But we also need a way to expose type information dynamically without casting. There is a way to implement abstract syntax trees in an object-oriented language that balances these competing forces: the visitor design pattern. Feel free to ask me about it if you'd like to learn more, or read about the visitor design pattern on your own.