January 28, 2026 6:56 PM

This and That, January 28 Edition

I need to write titles that distinguish This and That posts, so here you have the January 28 edition.

It's Books

A delightful paragraph from Linda Liukas:

At Hatchard's I was waiting for B. who had vanished into the first and modern editions section. An older husband was already exasperated: I've been calling you several times, he sighed down the stairwell. His wife emerged, unbothered, brushing past him: Oh, it's books, darling, as if that settled not only the argument but the entire question of how to live.

"... as if that settled not only the argument but the entire question of how to live." Beautiful.

Hat tip Robin Sloan.

Money on the Table

Joan Westenberg in Why My Newsletter Costs $2.50:

The instinct to leave money on the table in exchange for a better relationship with your audience is neither naive nor unsophisticated.

Most CS faculty leave money on the table to work with students in a way that only colleges and universities offer.

Way to Sell the Downside

From Dan Wang's 2025 letter:

While critics of AI cite the spread of slop and rising power bills, AI's architects are more focused on its potential to produce surging job losses. Anthropic chief Dario Amodei takes pains to point out that AI could push the unemployment rate to 20 percent by eviscerating white-collar work. I wonder whether this message is helping to endear his product to the public.

I was glad to see Dan write a 2025 letter after taking a break last year to work on his book. This letter is worth a read, as always. As much as I learn from and think about his writing on China and American policy, I really enjoy the parts about books and culture more broadly.

January 11, 2026 8:56 AM

This and That

A few items from recent weeks...

Writing Code Is Fun

David Celis, in a post of the same name:

When someone's primary job is to figure out and write requirements or manage the entities who are actually producing the code, we don't usually call that person a software engineer. We call them a product or project manager.

Not, as Celis goes on to say, that there's anything wrong with that. But I like to write code. For that purpose, looking up an answer in language documentation or on StackOverflow serves me fine.

I'm not ready to turn writing code over to an assistant programmer. When I do want to work with an assistant, though, I work with a student. I'd rather help a student learn to design and write code than help somebody's LLM gather more data.

Being a Beginner

Asha Dornfest, in You, too, can be an urban sketcher:

There's a spark of aliveness that comes with being a beginner. A combo of shock and giddiness when you do something you thought you couldn't do. The intense focus that comes when there's no prior experience to fall back on. The possibility of new and exciting things within your grasp, like finding hidden treasure inside your house.

Hat tip to Daniel Steinberg.

More Confident a Year Ago

From comments by an exec at Salesforce:

All of us were more confident about large language models a year ago...

This is a Senior Vice President of Product Marketing, talking about why Salesforce is rethinking its "heavy reliance on large language models after encountering reliability issues". It turns out that "predictable 'deterministic' automation" is more reliable.

Huh. It turns out regular old programs do many tasks really well.

December 30, 2025 8:43 PM

My /ai Page

I'm not sure where I first heard about /ai pages.

Damola Morenikeji may have been the first

to explain the idea:

generative AI is getting so good that readers won't be able to

tell if the text they are reading was written by a person or

generated by an LLM. One way for a writer to engender trust is

to be transparent, by linking to a page that tells readers how

AI is used on the site.

I ran across

Derek Sivers's /ai page

again recently and decided I would have one, too.

So, I have created

https://www.cs.uni.edu/~wallingf/ai.html.

The one-line answer to "How does Eugene use AI on this site?" is: not at all, and certainly not on this blog.

If you see any text here that isn't a quotation of another person's work, then I wrote the text myself. That page elaborates a bit on my thinking, but it all boils down to the fact that I like to write and don't want to outsource my writing to a program. If I want to have a writing assistant, I'll work with a student.

My /ai page does describe one time I used an LLM as

part of a research project:

I have used large language models (LLMs) in a research project with a student. The student and I worked with a prospective author to train an LLM on the public writing of a well-known educator from history. We then queried the model to see what the educator might say about some modern issues in education and public policy. For me, this is just the sort of project for which LLMs offer a potential benefit that would be hard to attain in another way.

By the way, this is a really cool project... I've been meaning to write more about it here, but it's not ready yet for public exposure. Besides, I'm sensitive to the externalities imposed on creators and on the environment by VC-backed generative AI systems, so I'm reluctant to promote their use any more than the current AI bubble is promoting them.

Anyway, I have an /ai page now. I doubt my stance

on generative AI is likely to change significantly in the future.

I like to write, I like to program, and I like for the presence

of my name on a piece of work to reflect my personal investment

in that work. If that changes, I will update the page.

December 26, 2025 6:28 PM

"Source code is the literature of computer scientists."

Recently, a link to the 2013 Computer History Museum article Adobe Photoshop Source Code was going around my social media feed.

That first version of Photoshop was written primarily in Pascal for the Apple Macintosh, with some machine language for the underlying Motorola 68000 microprocessor where execution efficiency was important. It wasn't the effort of a huge team. Thomas said, "For version 1, I was the only engineer, and for version 2, we had two engineers." While Thomas worked on the base application program, John wrote many of the image-processing plug-ins.

I'm not sure why a 12-year-old article about a 35-year-old software application popped back into everyone's attention, but it brought back good memories for me. My history with Photoshop does not go all the way back to the beginning of Photoshop, but it does go back to my beginning as a faculty member.

In 1992, I started as a brand-new assistant professor. A colleague worked with me to set up my office and lab computing equipment: a Macintosh Quadra 950, a massive Apple display (*), and a bunch of complementary hardware and software, including a flatbed scanner from LaCie, OmniPage OCR software — and Photoshop. I felt like I was living in the future.

(*) This display got warm... really warm. One day that year, I was down the hall teaching an AI lab section when we all smelled burning wire. My display had spontaneously combusted. Fortunately, we turned it off soon enough to avoid setting off the alarm and inviting a visit from the fire department.

With permission from Adobe, the Computer History Museum provides access to the source code of Photoshop 1.0.1 from 1990:

All the code is here with the exception of the MacApp applications library that was licensed from Apple. There are 179 files in the zipped folder, comprising about 128,000 lines of mostly uncommented but well-structured code. By line count, about 75% of the code is in Pascal, about 15% is in 68000 assembler language, and the rest is data of various sorts.

Pascal — another connection to 1992 Eugene.

That first semester as a prof, I taught Pascal in our intro course, something I did again for the next couple of years. I had fun. Teaching programmers to beginners is a challenge that rewards you every time the light goes on in a student's eyes. Besides, Pascal had become one of my go-to languages halfway through my undergrad years, and I loved writing Pascal programs every day. It remains a favorite to this day, though I haven't written any Pascal in many, many years.

In the coming year, I intend to dive into the Photoshop source and see what I can learn from it. I like reading source code. This line from the CHM article says it all:

Software source code is the literature of computer scientists, and it deserves to be studied and appreciated.

December 16, 2025 7:41 PM

A Brave New World in the College Classroom

... or, "How a Pair of Smart Glasses Jogged My Memory"

Earlier today, a student in my department tried to take a final exam while wearing Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses. Fortunately, the prof noticed.

Now we get to monitor our students' eyewear. Good times.

We now range from students who can't afford to buy textbooks in their effort to learn, to kids who can afford to buy smart glasses in their effort not to.

As someone commented on Mastodon,

the thing that really sucks is that smart glasses ... can help with accessibility and have very valid use cases, but they are already so misused that any wearing of them is suspect now.

Likewise, LLMs may also have a valid use in support of student learning (*), but right now their dominant use among students seems to be as the sort of crutch that inhibits learning — which accounts for the desperation come exam time.

(*) modulo their negative externalities, of course

Unfortunately, a student who does not confront their lack of learning until exam time, even if only by being unable to perform, generally ends up paying a steep price.

After all these years teaching, I have a lot of sympathy for students who feel desperate enough to cheat. Yes, they put themselves in a bad position, often after their instructor has made a significant effort to inform them about appropriate ways to use technology in support of learning and to explain the risks of inappropriate uses. And yes, they are accountable for their own behavior.

Still, a part of me thinks of the adage, "There but for grace of God go I..."

The year is fourth grade; I am taking a science test. I want to say that the test was on the six simple machines, but it might have been on a biology topic. At this great distance, memory is unreliable...

In any case, I forgot one item from a list. Either I knew that I was underprepared for the exam, or I had simply rushed in the moments before it started, because my science notebook was open on top of the pile of papers inside my flip-top desk. I opened my desk, saw the list, and filled in the final answer.

The teacher noticed.

Mrs. Bell came to my desk, looked at my paper, and asked what had had happened. I told the truth. She shook her head and told me she was disappointed in me.

That was like a dagger. I was the sort of student who wanted to please all authority figures. But this wasn't me disappointing just any teacher. I loved Mrs. Bell. She remains to this day my all-time favorite teacher. She was a huge influence on me.

(Here's another memory: I remember once saying to Mrs. Bell something like, "I don't know if I'll go to college." She smiled and said, "Eugene, college was invented for people like you." From that moment forward, I never doubted my educational future.)

Anyway: I don't recall what else she did or said in that moment. Did she dock me points? Make me take a new test? I don't even know if she told my parents, but I don't think so. If she did, they never said anything about. They, like Mrs. Bell, knew me well enough to know how I embarrassed I was by doing something so wrong and, yes, being caught.

Whatever else she did or said, I remember her calm demeanor and her personal response to me.

The cost of failing a test in the fourth grade is significantly less than the cost of failing a final exam in college, or of failing a course. So, I may have been saved from paying a much steeper price later by succumbing to a temptation much earlier and paying the price then. I was also saved by a generous and loving teacher who knew just how to respond to the particular student in front of her at that moment. What she did and how she treated me obviously made an impression.

I can only hope that my colleagues and I have the wherewithal to respond in such situations in a way that both holds our students accountable (yes, that's important) and helps them learn from what could be a traumatic experience. Unfortunately, I think we are going to have plenty of opportunities.

November 27, 2025 8:10 PM

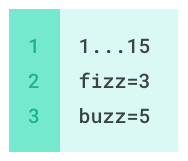

Fizzbuzz, Functional Style

Ask, and ye shall receive.

In yesterday's post, I reported on an attempt to solve the classic Fizzbuzz problem in a functional style. Near the end of the post, I wrote:

This solution is fun but feels a little unsatisfactory. I'm not as fluent with functional programming as I am with OOP. Perhaps there is a more idiomatic FP way to do this? Let me know.

Thanks to everyone who responded with ideas and conversation!

Chris Johnson offered a couple of different approaches and ended up with a slick solution that is fully functional: create an array containing the different values to print, then use cycled values for Fizz and Buzz to construct an index into the array.

Here's an elegant solution in Haskell, courtesy of Chris:

pick :: (Int, Int, Int) -> String pick (f, b, n) = [show n, "Fizz", "Buzz", "FizzBuzz"] !! (f + b)main = do let fizzes = cycle [0, 0, 1] let buzzes = cycle [0, 0, 0, 0, 2] mapM_ putStrLn $ take 30 $ map pick $ zip3 fizzes buzzes [1..]

Beautiful. 1 (= 1 + 0), 2 (= 0 + 2), and 3 (= 1 + 2) select the appropriate word to print in cases divisible by 3 and/or 5, and 0 (= 0 + 0) selects the number as a default. Beyond that, the code is a couple of maps on top of a zip.

This technique reminds me of a similar trick Joe Bergin used when we ran the Polymorphism Challenge workshop back in 2005, solving one problem by looking up in an array an object to send a message to. I'd completely forgotten that solution until I saw Chris's!

Racket is not as concise as Haskell for a problem like this, but a Racket solution is nice, too.

First, here's choose:

(define (choose f b n)

(let ((answers (vector (number->string n) "Fizz" "Buzz" "FizzBuzz")))

(vector-ref answers (+ f b))))

Then we define the cycles:

(let ((fizzes (cycle '(0 0 1) size))

(buzzes (cycle '(0 0 0 0 2) size))

(numbers (range 1 (add1 size))))

...)

Finally, the code to implement the functional idea is:

(map displayln

(map (lambda (L) (apply choose L))

(zip fizzes buzzes numbers)))

I have to apply choose to the zipped lists because

Racket doesn't have a destructuring define form.

Of course, Racket is a language for making languages, so we

can create one if we'd like! I've written a three-place form

hardcoded to handle (define-match (choose (f b n)) ...),

but I'll have to do some work to generalize it to take lists of

any size.

Thanks again to everyone who wrote in response to my post, and especially to Chris for the fine solution. Readers of this blog continue to teach me new things. I hope they find some value in my posts, all too rare these days. In any case, I have much to be thankful for on this Thanksgiving Day.

November 25, 2025 1:33 PM

A Polymorphism Challenge, Functional Programming Style

in the Fizzbuzz language

Over the weekend I ran across a blog post by Evan Hahn in which he took on this exercise:

... write Fizz Buzz with no booleans, no conditionals, no pattern matching, or other things that are like disguised booleans.

Ah, the memories! In 2005, Joe Bergin and I ran a SIGCSE workshop

called The Polymorphism Challenge, which I mentioned briefly in

a trip report

at the time and reported more fully in

a 2012 post.

The goal of that workshop was to help participants learn how to use

polymorphic objects to solve a variety of standard problems without

relying on if statements to select among different

conditions. It was great fun, and many of the workshop participants

found it both challenging and enlightening.

Hahn's post gives a functional solution to Fizzbuzz in Python, using iterators and a creative, though limited, string mask:

from itertools import cycledef string_mask(a, b): return b + a[len(b):]

def main(): fizz = cycle(["", "", "Fizz"]) buzz = cycle(["", "", "", "", "Buzz"]) numbers = range(1, 101) for f, b, n in zip(fizz, buzz, numbers): print(string_mask(str(n), f + b))

I thought, hey, I can do that in Racket:

(define string-mask

(lambda (num-str fb-str)

(string-append fb-str

(guarded-substring num-str

(string-length fb-str)))))

(define fizzbuzz

(lambda (max)

(let ((fizz (cycle '("" "" "Fizz") max))

(buzz (cycle '("" "" "" "" "Buzz") max))

(numbers (range 1 (add1 max))))

(for ((f fizz)

(b buzz)

(n numbers))

(displayln (string-mask (number->string n)

(string-append f b)))))))

Two notes:

-

I wrote my own

cyclefunction. Racket has asequence->repeated-generatorfunction inracket/generator, which behaves likecyclein Python'sitertools, but I wanted to write a simpleforover lists. -

I had to create a substring function that allows the

start index to be out of bounds. Racket's native

substringis more careful than Python's [:].

The string masking idea is clever, but Hahn points out that it starts to fail when the number is long enough that the Fizzbuzz string can't cover it all.

This solution is fun but feels a little unsatisfactory. I'm not as fluent with functional programming as I am with OOP. Perhaps there is a more idiomatic FP way to do this? Let me know.

Bonus code: If you want to see a solution that will melt your face, check out this article implementing Fizzbuzz in the array language Q. I learned APL on 1985 or so, and its way of thinking will always have a strange hold on my brain!

Anyway, that was a nice diversion for a few minutes during Thanksgiving break. As I tell my students almost every day in class, I like to program. I'm thankful that I am able to do it.

October 05, 2025 1:40 PM

On My Way, Rejoicing

This passage is spoken by the protagonist in Muriel Spark's 1981 novel Loitering with Intent:

I found the book on the library shelves and while I was there in that section, I lit upon another book I hadn't seen for years. It was the /Autobiography/ of Benvenuto Cellini. It was like meeting an old friend. I borrowed both books and went on my way rejoicing.

I don't know anything about Cellini or his autobiography, but I know this feeling well. Stumbling onto an unexpected book at the library gives me almost unreasonable joy.

Loitering with Intent is my second Spark novel, after Finishing School. I gave Spark a try on recommendation of her work by Henry Oliver at The Common Reader. Oliver also reignited my interest in the novels of Penelope Fitzgerald, whose The Bookshop I first read years ago... after stumbling across a copy on the shelf of my local library. Fancy that.

September 08, 2025 3:52 PM

An Incredible Triumph of Human Cooperation

I went to this blog post by Jordan Ellenberg for the baseball (well, that's not quite true — I read all his posts) and left feeling a kinship with him in this regard:

Wikipedia is really an incredible triumph of human cooperation. Why does it work so well? How is it so unpolluted? How is it that when some very weird niche question like "which pitchers have beaten all 30 teams?" comes to my mind, some human being has already compiled this and put it there? I don’t know. But I'm glad it exists.

I remember back when Wikipedia first began, how so many people were convinced that it could not work. Having been active on Ward Cunningham's C2 wiki in the 1990s, I knew that it could, but I wasn't sure how the idea would scale to include anyone and everyone with net access.

I grew up reading the encyclopedias on the basement shelves in our family home, trying to soak up everything under the sun. How could a collaboratively built website with no authoritative gatekeeper match those volumes?

Nearly twenty-five years later, I can say that Wikipedia has succeeded beyond my imagination. Sure, it faces challenges with some contentious topics. However, for almost anything I might want to learn something about — even weird niche questions like "Which pitchers have beaten all 30 teams?" — I usually count on Wikipedia for an answer. People love to build and share knowledge.

August 31, 2025 9:31 AM

Another Old Person in the Room of the Cybersecurity Knowledge

This passage from an interview with Lesley Carhart was a shot in the arm I needed:

You've spoken about the risk of younger generations relying too heavily on tools and AI without learning the basics. Are you worried we're losing critical knowledge?

I struggle sometimes with how to convey this without sounding like the "old person" in the room. But there really is a problem. Since I started in this field, universities everywhere have launched cybersecurity degrees, and many of them are fundamentally flawed because they don't teach the foundations of computing.

We now have a generation that hasn't been exposed to the inner workings of computers. Everything is point-and-click, tablets, and touchscreens, so they don't learn at home how computers actually work. Then they enroll in cybersecurity programs, but those programs also don't teach fundamentals. Instead, they teach how to use tools—EDR, Metasploit, whatever's current. And tools change constantly. In cybersecurity, tools and techniques are outdated within a few years. Without foundations, students can't adapt, and they can't work with legacy systems. That's a big problem.

I am not a specialist in cybersecurity, so it's heartening for me to hear someone with Carhart's experience and expertise say this about cybersecurity curriculum.

My department has offered a degree program called Networking and System Administration (NaSA) for over twenty years. With the rapid growth of cybersecurity programs at community colleges, and increasing interest from high school students, there is a strong desire among admissions staff and upper administrators for us to offer a cybersecurity program. The NaSA major has long taught some of the essential skills of cybersecurity, so we are evolving it to focus more directly on cybersecurity.

However, our program will continue to teach the fundamentals that Carhart says are important. It will have a small intro CS core, plus standard courses in operating systems and networks — and statistics, knowledge of which is essential for studying system behavior and machine learning.

This focus on fundamentals creates challenges. It's hard to make room for all the tools and techniques that students need to know now. But, as Carhart says, many of those tools and techniques will be outdated within a few years. We are preparing students for long careers, and to be contributors and citizens in a complex social world. Even if we approach the task from a purely technological perspective, though, without foundations, students would struggle to adapt to the changes we know are coming.

A foundations-centered program also creates practical challenges in the world of university admissions, because it makes it harder for community college students to parlay their CC degrees into immediate university credits. That's a big deal in a world where enrollment drives university budgets and CC students are a primary audience.

We're working on all of these challenges. We are slowly figuring things out. But it's encouraging to know that an expert such as Carhart appreciates the need for cybersecurity students to learn the foundations of computing. We think they are important, too.