Session 11

Recursive Functions and Loops

Download this Racket file to use as you work through Session 11.

A Warm-Up Exercise

As we have seen, map is a higher-order function

that's awfully handy for solving problems with lists. However,

it does not work the way we want when used with nested lists such

as the s-lists we learned about last

time. So let's make our own special-purpose map!

Let's work with a new kind of nested list, the n-list. N-lists are just like s-lists, but with numbers:

<n-list> ::= ()

| (<number-exp> . <n-list>)

<number-exp> ::= <number>

| <n-list>

Now, for the exercise:

(map-nlist f nlist), where

f is a function that takes a single number argument

and nlist is an n-list.

map-nlist returns a list with the same structure as

nlst, but where each number n has been

replaced with (f n). For example:

> (map-nlist even? '(1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64)) '(#f #t #f #t #f #t #f #t) > (map-nlist add1 '(1 (4 (9 (16 25)) 36 49) 64)) '(2 (5 (10 (17 26)) 37 50) 65)

map-nlist should be mutually recursive with

map-numexp, which operates on

number-exp.

For a twist:

-

If you are seated on the left side of the room, write

map-nlistfirst, assuming thatmap-numexpalready exists. -

If you are seated on the right side of the room, write

map-numexpfirst, assuming thatmap-nlistalready exists.

If you finish before I call time, write the other function, too.

Using Mutual Recursion to Implement map-nlist

The definition on n-list is mutually inductive, so let's use

mutual recursion.

The code will look quite a bit like our mutually-recursive

subst function

from last time.

The result is something like this:

(define (map-nlist f nlst)

(if (null? nlst)

'()

(cons (map-numexp f (first nlst))

(map-nlist f (rest nlst)))))

(define (map-numexp f numexp)

(if (number? numexp)

(f numexp)

(map-nlist f numexp)))

This is quite nice. map-nlist says exactly what it

does: combine the result of mapping f over the

numbers in the car with the result of mapping

f over the numbers in the cdr. There

is no extra detail.

map-numexp is the function that applies the function

f, because it is the only code that ever sees a

number! If it sees an n-list, it lets map-nlist do

the job.

With small steps and practice, this sort of thinking can become as natural to you as writing for loops and defining functions in some other style.

Recap: Writing Recursive Programs

Introduction

In the last two sessions, we have studied how to write recursive programs based on inductively-defined data. Our basic technique is structural recursion, which asks us to mimic the structure of the data we are processing in our function. We then learned two techniques for writing recursive programs when our basic technique needs a little help:

- interface procedures — When our structurally-recursive function requires an argument that the function specification does not provide, we turn it into a helper function. The specified function passes its original arguments to the helper, along with an initial value for the new argument.

- mutual recursion — When our inductive data definition includes two data structures that are defined in terms of one another, we write two functions that are defined in terms of one another.

Program Derivation

In your reading for this time, you also encountered the idea of program derivation. Mutual recursion creates two functions that call each other. Sometimes, the cost of the extra function calls is high enough that we would like to improve our code, while remaining as faithful as possible to the inductive data definition. Program derivation helps us eliminate the extra function calls without making a mess of our code.

Program derivation is a fancy name for an idea we already understand at some level. In Racket, expressions are evaluated by repeatedly substituting values. Suppose we have a simple function:

(define (2n-plus-1 n) (add1 (* 2 n)))

Whenever we use the name 2n-plus-1, Racket

evaluates it and gets the lambda expression that

it names. To evaluate a call to the function, Racket does what

you expect: it evaluates the arguments and substitutes them for

the formal parameters in the function body. Thus we go from the

application of a named function, such as:

(2n-plus-1 15)

to the application of a lambda expression:

((lambda (n)

(add1 (* 2 n)))

15)

If we stopped here, we would still be making the function call. But we can apply the next step in the substitution model to convert the function call into this expression:

(add1 (* 2 15))

Our compilers can often do this for us. As noted in your

reading on program derivation, a Java compiler will generally

inline calls to simple access methods, and C++ provides

an inline keyword that lets the programmer tell

the compiler to translate away calls to a specific function

whenever possible.

As a programming technique, program derivation enables us to refactor code in a way that results in a more efficient program without sacrificing too many of the benefits that come with writing a second function.

Relationships Among the Recursive Programming Patterns

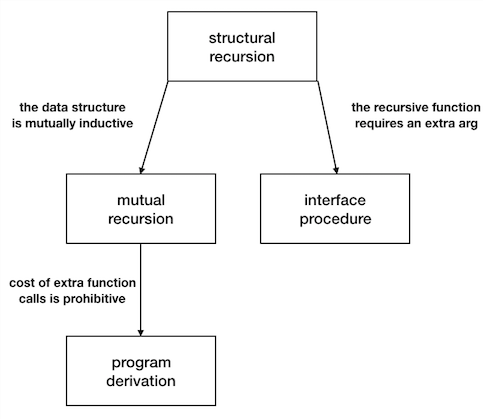

With program derivation, we have now seen four recursive programming patterns. We start with structural recursion and apply the other patterns when we encounter specific issues.

These patterns will guide us as we write functions to process any inductively-defined data types.

A Program Derivation Exercise

map-nlist into

a single function.

(define (map-nlist f nlst)

(if (null? nlst)

'()

(cons (map-numexp f (first nlst))

(map-nlist f (rest nlst)))))

(define (map-numexp f numexp)

(if (number? numexp)

(f numexp)

(map-nlist f numexp)))

map-nlist, Refactored

First, we substitute the lambda for the name:

(define (map-nlist f nlst)

(if (null? nlst)

'()

(cons ((lambda (f numexp)

(if (number? numexp)

(f numexp)

(map-nlist f numexp)))

f (first nlst))

(map-nlist f (rest nlst)))))

... and then the partially-evaluated body for the

lambda:

(define (map-nlist f nlst)

(if (null? nlst)

'()

(cons (if (number? (first nlst))

(f (first nlst))

(map-nlist f (first nlst)))

(map-nlist f (rest nlst)))))

This eliminates the back-and-forth function calls between

map-nlist and map-numexp. The primary

cost is an apparent loss of readability: the resulting function

is more complex than the original two. Sometimes, that trade-off

is worth it. As you become a more confident Racket programmer,

you will find the one-function solution a bit easier to grok

immediately.

We will use program derivation only when we really need it, or when the resulting code is still small and easy to understand.

Quick Exercise: Expensive Recursion

When we first learn about recursion, we often use it to implement

functions such as factorial and fibonacci. Here

is what the typical factorial function looks like

in Racket:

(define factorial

(lambda (n)

(if (zero? n)

1

(* n (factorial (sub1 n))))))

Back in Session 2, though, I showed you an odd-looking implementation:

(define factorial-aps

(lambda (n answer)

(if (zero? n)

answer

(factorial-aps (sub1 n) (* n answer)))))

> (factorial-aps 6 1)

720

Odd, indeed.

factorial-aps, this is how the

computation starts:

(factorial-aps 6 1) ; the function call (factorial-aps 5 6) ; the first recursive callYour task: Write down the rest of the recursive calls.

Tail Recursion

You may wonder why factorial-aps is written this way.

But notice: It passes a partial answer along with every recursive call and returns that partial answer when it finishes.

In a very real sense, this function is iterative. It

counts down from n to 0, accumulating partial solutions

along the way. Consider the sequence of calls made for

n = 6:

(factorial-aps 6 1) (factorial-aps 5 6) (factorial-aps 4 30) (factorial-aps 3 120) (factorial-aps 2 360) (factorial-aps 1 720) (factorial-aps 0 720)

This function is also imperative. Its only purpose on

each recursive call is to assign new values to n and

the accumulator variable. In functional style, though, we pass

the new values for the "variable" as arguments on a recursive

call.

That sounds a lot like the for loop we would write

in an imperative language. On each pass through the loop, we

update our running sum and decrement our counter. In Python,

the n = 6 example is:

n = 6

answer = 1

while (n > 0):

answer = n * answer

n = n - 1

At run time, factorial-aps can be just like

a loop!

Consider the state of the calling function at the moment it makes its recursive call. The value to be returned by the calling function is the same value that will be returned by the called function! The caller does not need to remember any pending operations or even the values of its formal parameters. There is no work left to be done.

The first call to the function is (factorial-aps 6 1).

The formal parameters are n = 6 and

answer = 1. The value of this call will be the value

returned by its body, which is:

(if (zero? n)

answer

(factorial-aps (- n 1) (* n answer)))

n is not zero, so the value of the if expression will

be the value of the else clause. The else clause is

(factorial-aps (- n 1) (* n answer))

which means that the recursive function will call be:

(factorial-aps 5 6)

Whatever (factorial-aps 5 6) returns will be returned

as the value of the else clause, which becomes the

value of the if expression, which becomes the value

of (factorial-aps 6 1).

That's what we mean above: The value to be returned by the calling

function — which is (factorial-aps 6 1) —

will be the same value that is returned by the called function

— which is (factorial-aps 5 6). When

(factorial-aps 5 6) returns a value,

(factorial-aps 6 1) passes it on as its own answer.

In programming languages, the last expression to evaluate in order to know the value of an expression is called the tail call. We call it that because it is the "tail" of the computation.

In the case of factorial-aps, the tail call is a call

to factorial-aps itself. In programming languages,

we call this function tail recursive.

When a function is tail-recursive, the interpreter or compiler can take advantage of the fact that the value returned by the calling function is the same as the value returned by the called function to generate more efficient code. How?

It can implement the recursive call "in place", reusing the same stack frame:

- First, it stores the values passed in the tail call into the same slots that hold the formal parameters of the calling function.

-

Second, it replaces the function call with a

gotostatement, transferring control back to the top of the calling function.

(lambda (n ans) | (lambda (n ans)

(if (zero? n) | (if (zero? n)

ans | ans

| {

(factorial-aps (sub1 n) | n := (sub1 n)

(* n ans)))) | ans := (* n ans)

| goto /if/

| }))

Observing This Behavior with trace

We can see this behavior with the help of a Racket module named

racket/trace. Add these lines to the source file

containing factorial-aps and factorial:

(require racket/trace) (trace factorial) (trace factorial-aps)

Now call (factorial 6). The function shows us its

behavior on the run-time stack, adding a new stack frame with

each recursive call.

Then call (factorial-aps 6 1). This function shows

its behavior, too. There are no new stack frames, only changes

to the parameters on the original stack frame.

This is how Racket can be so efficient for many recursive functions. It does not generate new stack frames!

Proper Handling of Tail Calls

The Scheme language definition specifies that

every Scheme interpreter must translate tail calls

into equivalent gotos. Racket, a descendant of

Scheme, is faithful to this handling of tail calls.

Not all languages do this. The presence of side effects and other complex forms in a language can cause exceptions to the handy return behavior we see in tail recursion. Compilers for such languages often opt to to be conservative.

For example, Java does not handle tail calls properly, and

making it do so would complicate the virtual machine a bit. So

the handlers of Java have not made this a requirement for

compilers. Likewise for Python. Still, many programmers think

it might be worth the effort. Some Java compilers do optimize

tail recursion under certain circumstances, as does the GNU

C/C++ compiler gcc. Tail recursion remains an

active topic in programming languages.

With their lack of side effects, functional programming languages are a natural place to properly handle tail calls. In addition to Racket, languages such as Haskell make good use of tail call elimination. That leads to some interesting new design patterns as well.

In functional programming, we use recursion for all sorts of repetitive behavior. We often use tail recursion because, as we have seen, the run-time behavior of non-tail recursive functions can be so bad. In other cases, we use tail recursion because structuring our code in this way enables other design patterns that we desire.

The second argument to our factorial function above

is sometimes called an accumulator variable. How do we

create one when writing a recursive function? If you'd like to

learn more about this programming pattern, check out this

optional reading on accumulator variables.

Using an Interface Procedure to Implement positions-of

You had an opportunity to practice using interface procedures on Homework 4. It has an interesting property we can now see...

positions-of

required us to create a helper function that kept track of the

position number of each item in the list.

Notice: positions-of-at is naturally tail recursive!

Wrap Up

-

Reading

- Study today's lecture notes and the associated code.

-

If you'd like to review how to use Racket's

tracefunction, check out this short video by Colleen Lewis.

-

Homework

- Homework 4 was due last night.

- Homework 5 is available and is due in one week. They give you a chance to practice with structural recursion, in particular with mutual recursion.